Turning off a defense mechanism that protects colorectal cancer tumors from being discovered by immune cells could be a possible strategy for treating the disease, according to a new study by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators. Because immunotherapy reactivates immune cells near a tumor, but fails when those cells aren’t present in significant numbers, the new approach could potentially complement this type of treatment or work on its own.

The study, published Sept. 23 in Molecular Cell, found that turning off a gene that encodes an enzyme called protein kinase C iota (PKCi) allows the immune system to recognize tumors, recruit immune cells into the area, and ramp up the anti-tumor response to kill colorectal cancer cells in mice, shrinking their tumors. The team also found that people with colorectal cancer who have lower levels of PKCi have better outcomes.

“We found that the role of PKCi in colorectal cancer cells is to keep the immune system at bay,” said co-senior author Dr. Jorge Moscat, vice-chair for experimental pathology and the Homer T. Hirst III Professor of Oncology in Pathology in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Now, that we know what is happening we can try to reactivate the immune system to kill the tumor.”

Normally, the immune system should be able to find and kill cancerous cells, preventing tumors from ever forming, but some cancer cells have found ways to evade these defenses. Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint blockade therapy, is based on the idea that the immune cells in tumors are either exhausted or that their activity is being suppressed and that these cells can be reactivated to kill cancer cells.

“Immunotherapy reeducates the immune system to recognize cancer cells and kill them,” said Dr. Moscat, who is also associate director of shared resources in the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. “But it only works in small numbers of patients.”

He explained that about 85 percent of colorectal cancer tumors are so called “cold or immunoexcluded” tumors that don’t have any immune cells inside or near them. About 15 percent of colorectal cancer tumors have immune cells mixed in and patients with these tumors can be treated with immune check point blockade inhibitors, but they still only work half the time, he said.

“We wanted to find a way for the immune system to recognize colorectal cancer tumor cells, infiltrate the tumor, and kill the cells,” he said.

The investigators found that turning off the gene for PKCi in mice with colorectal cancer shrank their tumors. They also found that the interferon pathway, which helps rev up the immune response to cancer cells, is super-charged in these mice. Then, in a series of experiments on mouse colorectal cancer tumor cells grown in the laboratory, they showed that turning off the gene for PKCi attracts immune cells called CD8+ T cells that kill cancer cells.

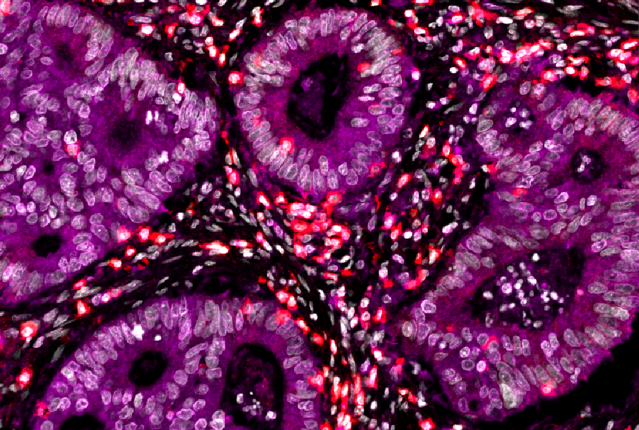

The team also analyzed how much PKCi enzyme was present in tumor samples from patients with colorectal cancer. They found that patients with less PKCi had less aggressive tumors and better outcomes than patients with higher levels of PKCi, confirming that PKCi also plays an important role in human cancers. Using powerful imaging and computer analysis capabilities in Weill Cornell Medicine’s Center for Translational Pathology, they showed that in individual human cancer cells with low levels of PKCi the interferon pathway ramps up to attract CD8+ T cells.

“The real breakthrough of the paper is that we’ve found the molecular mechanism that PKCi uses to control the interferon pathway,” said co-senior author Dr. Maria Diaz-Meco, the Homer T. Hirst III Professor of Oncology in Pathology and a member of the Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. This is important because it identifies several new potential targets for immune system boosting anti-cancer therapies.

The result could help fill the urgent need to develop new therapies for colorectal cancer, Dr. Moscat said. To achieve that goal, his first priority will be to work to develop drugs that can inhibit the activity of PKCi.

“By inhibiting PKCi we could turn immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” ones,” he said. A PKCi blocking drug alone may be enough to eliminate tumors, but if it is not, it might make tumors that normally wouldn’t respond to immunotherapy sensitive to treatments like immune check point inhibitors, which might finish the job. He and Dr. Diaz-Meco will also be studying other potential drug targets along this molecular pathway. Their discoveries may have implications for treating other types of cancers, but more studies will be needed to understand how important this pathway is in other cancers.

“We have to see how conserved this pathway is in other cancers,” Dr. Diaz-Meco said.