A protein called Zbtb46, expressed by specialized immune cells, has a major role in protecting the gastrointestinal tract from excessive inflammation, according to a study from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The finding, which appears July 13 in Nature, is a significant advance in the understanding of how the gut maintains health and regulates inflammation, which could lead to better strategies for treating diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“We’ve known that there are related families of immune cells in the gut that can either protect from inflammation or at other times be major drivers of inflammation,” said senior author Dr. Gregory Sonnenberg, the Henry R. Erle, M.D.-Roberts Family Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, and a member of the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine. “This new finding helps us understand how these cells are regulated to optimally promote intestinal health and prevent inflammation.”

IBD, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, affects several million people in the United States. These chronic inflammatory disorders target the gut, can be seriously debilitating, and treatments may not work well for some patients—mainly because scientists don’t have a complete picture of what is driving these diseases and how the sophisticated immune cell networks in the gut support tissue health.

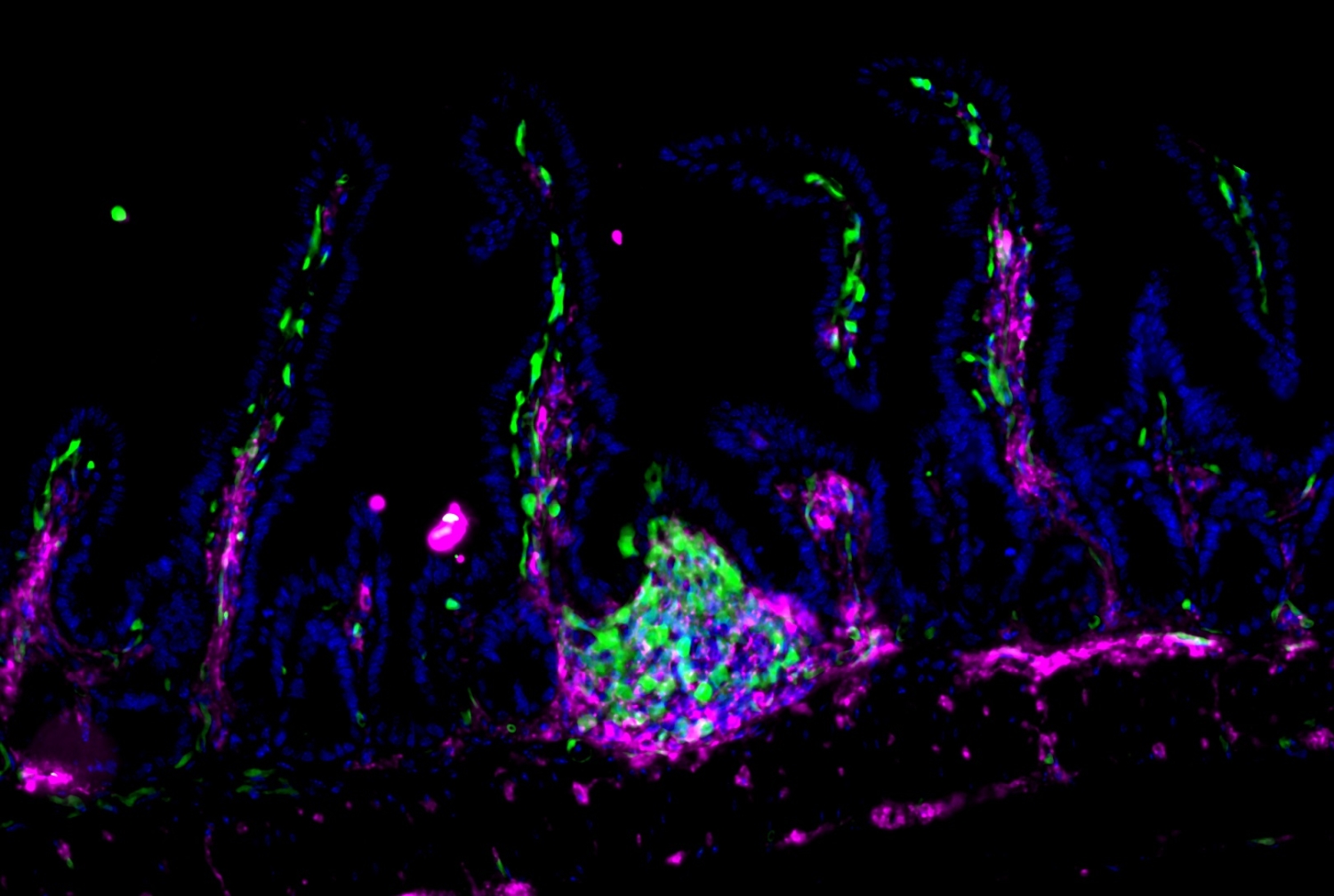

Dr. Sonnenberg’s laboratory has been advancing the science of gut immunity with studies of recently identified immune cells called ILC3s. These “innate lymphoid cells” are related to T cells and B cells, and clearly have important roles in protecting the gut and other organs from excess inflammation. However, in the context of IBD or colorectal cancer they become altered. In general, scientists have wanted to know more about how these cells work.

Drs. Gregory Sonnenberg and Wenqing Zhou. Photo credit: Roger Tully.

To this end, Dr. Sonnenberg and his team, including first author Dr. Wenqing Zhou, a postdoctoral researcher in the Sonnenberg Laboratory, set out to make a detailed catalog of ILC3s and other related immune cells residing in the large intestine of mice, using relatively new single-cell sequencing techniques.

A surprise finding was that a subset of ILC3s express Zbtb46, an anti-inflammatory protein that prior studies had suggested is produced only in dendritic cells, a very different type of immune cell. The researchers showed in experiments with mice that ILC3s expressing Zbtb46 have a strong ability to restrain inflammation following gut infection. When they blocked Zbtb46 expression in ILC3s, gut infection led to signs of severe inflammation, including a rise in the numbers of other gut immune cells promoting inflammation.

Dr. Robbyn Sockolow. Credit: Ashley Jones

The experiments indicated that Zbtb46 expression normally increases in mouse ILC3s in response to inflammation. Zbtb46 also has genetic links to pediatric IBD. Therefore, in collaboration with Dr. Robbyn Sockolow, professor of clinical pediatrics and chief of the division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition in the Department of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and a pediatric gastroenterologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children's Hospital and Center for Advanced Digestive Care; and the JRI Live Cell Biobank; the group next examined ILC3s from the gut of children with IBD and found higher Zbtb46 levels compared with ILC3s from healthy individuals—which is consistent with the idea that Zbtb46-expressing ILC3s have a role in people that is similar to their role in mice. Importantly, the expression level of Zbtb46 in ILC3s correlates with the severity of diseases in these children with IBD.

“This demonstrates a major role for this new pathway in responding to inflammation in the intestine of children with IBD, suggesting it could represent a novel therapeutic target,” Dr. Sockolow said.

Finally, the scientists found that Zbtb46-expressing ILC3s are also the main producers in the gut of a cytokine, IL-22, that protects against bacterial infection. Mice without the entire population of Zbtb46-expressing ILC3s are more susceptible to intestinal inflammation induced by gut infection.

“On the whole, our findings suggest a critical function of ILC3-intrinsic Zbtb46 in restraining gut inflammation, and a non-redundant role for Zbtb46-expressing ILC3s in protecting the gut following enteric infection,” Dr. Zhou said.

The next steps for Dr. Sonnenberg, Dr. Zhou and their colleagues will include studies to determine precisely how Zbtb46—a transcription factor protein that binds to DNA to control other genes’ expression levels—exerts its anti-inflammatory effects. Ultimately, they hope, future drugs that boost Zbtb46-related anti-inflammatory signaling could help treat IBD patients.

Dr. Sonnenberg added that, in principle, drugs that block Zbtb46-related signaling might be useful in situations, including some cancers, where enhancing immune activity is desirable. This is an active area of investigation in his laboratory.

Research in the Sonnenberg Laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI143842, R01AI123368, R01AI145989, U01AI095608, R21CA249274, R01AI162936 and R01CA274534); an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; the Meyer Cancer Center Collaborative Research Initiative; The Dalton Family Foundation; and Linda and Glenn Greenberg. Wenqing Zhou is supported by a fellowship from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation (831404). Dr. Sonnenberg is a CRI Lloyd J. Old STAR. The JRI IBD Live Cell Bank is supported by the JRI, Jill Roberts Center for IBD, Cure for IBD, the Rosanne H. Silbermann Foundation, the Sanders Family and Weill Cornell Medicine Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.