Women become more susceptible to hypertension as they approach menopause, and now a preclinical study led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine’s Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute suggests that this “perimenopausal” hypertension may be driven by declines in estrogen signaling in a brain region called the hypothalamus—and may be preventable with estrogen-like treatments.

In the study, published May 3 in the Journal of Neuroscience, the researchers, led by Drs. Teresa Milner and Michael Glass, respectively a professor and associate professor of neuroscience in Weill Cornell Medicine’s Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute, used mice to model the perimenopausal decline in the production of estrogen by the ovaries.

The scientists found that female mice with a low-estrogen condition resembling human perimenopause become more susceptible to experimentally induced hypertension—but lose that susceptibility when estrogen signaling is boosted again with an estrogen receptor (ER) β-stimulating “agonist” drug.

The results, say the researchers, suggest that ERβ agonists might be beneficial in preventing or treating hypertension in perimenopausal women.

Prior research in this area was hampered by the lack of good animal models for the pattern of perimenopausal changes in estrogen production in people. However, the mice used in the study undergo a form of ovarian failure that leads to erratic estrogen fluctuations and other hormone-related changes closely resembling those of human perimenopause.

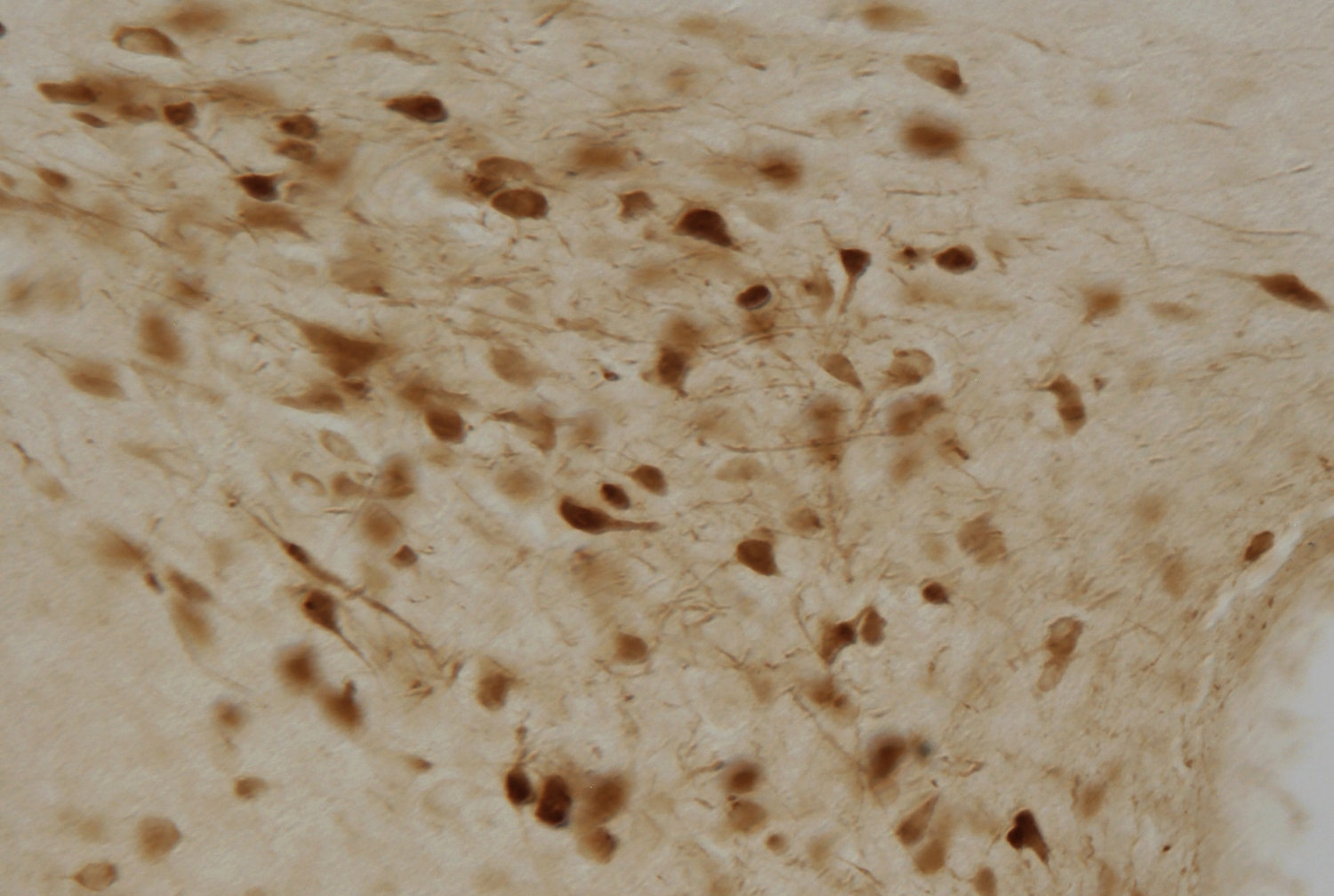

As part of the study, the researchers identified a tiny, blood-pressure controlling brain area within the hypothalamus, called the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), as an important site where estrogens are likely to act to regulate blood pressure.

Specifically, the researchers found that in their mice, perimenopause-like ovarian failure leads to a loss of signaling through ERβ receptors in PVN neurons. These ERβ signals normally have the regulatory role of dialing down the sensitivity of PVN neurons to incoming excitatory signals via glutamate receptors called NMDA receptors. When this regulatory ERβ signaling drops off, the sensitivity of PVN neurons to these excitatory inputs goes up.

That jump in sensitivity, and an accompanying increase in the production of highly reactive oxygen-containing molecules by PVN neurons, contribute to rises in blood pressure, the researchers concluded. They observed similar rises when they used a chemical compound to block ERβ signaling. But restoring ERβ signaling with ERβ agonists essentially restored normal blood pressure.

In principle, Drs. Milner and Glass said, preventing hypertension by maintaining estrogen’s blood pressure-regulating function could have wider implications for healthy aging in women. Hypertension is associated with major age-related diseases including heart disease, stroke, kidney failure and Alzheimer’s disease.