SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing the global COVID-19 pandemic, can infect human pancreatic cells and alter their physiology, according to research from Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian investigators. Though the results come from analyses of autopsy samples and cultured cells and don't prove a direct causal relationship, they dovetail with clinical reports of glucose control problems in COVID-19 patients, suggesting a new dimension of disease development for a virus that has already killed millions.

Some of the same researchers had previously generated multiple cell types from human stem cells and tested them to see which ones SARS-CoV-2 could infect. The intent of that work was to survey the spectrum of tissues that might be infected during COVID-19, a disease with a diverse array of symptoms in different patients.

"What we found is that as expected, lung can be infected, but very surprisingly we find pancreatic beta cells can also be infected," said Dr. Shuibing Chen, the Kilts Family Associate Professor of Surgery, an associate professor of chemical biology in surgery and of chemical biology in biochemistry at Weill Cornell Medicine, and co-senior author on the new study, which was published May 19 in Cell Metabolism. Beta cells, which produce insulin, are crucial regulators of blood glucose levels, and pathologies in these cells can cause diabetes. At the same time, Dr. Chen said, some physicians have reported unstable glucose and insulin levels in COVID-19 patients, which would be consistent with the virus causing damage to the beta cells.

“However it is not clear whether the virus is present in the pancreas,” said co-senior author Dr. Robert Schwartz, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and a faculty member in the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences’s Physiology, Biophysics and Systems Biology program at Weill Cornell Medicine.

To explore whether the virus might be able to cause such damage, Drs. Chen, Schwartz and their colleagues and collaborators at Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the National Institutes of Health, and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania took a two-pronged approach: looking for SARS-CoV-2 in pancreatic tissue taken at autopsy from patients who'd died of COVID-19, and further probing SARS-CoV-2 infection of stem cell-derived pancreatic cells in culture.

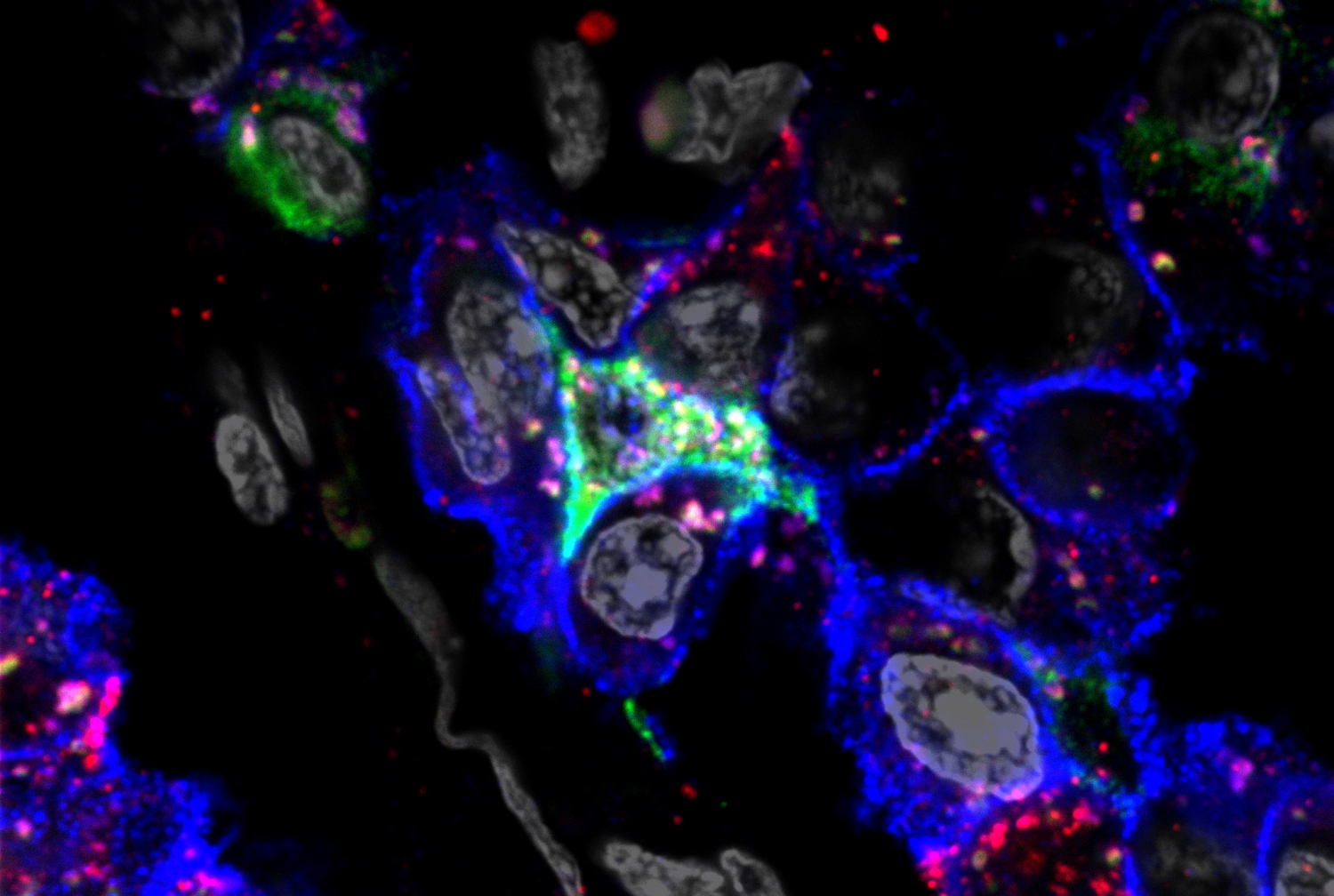

"We screened a lot of pancreatic autopsy samples and eventually we found five patients who had very robust viral RNA, and who also had very robust staining of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in different endocrine cells," Dr. Chen said. The combination of viral RNA genomes and viral protein antigens strongly suggests the presence of viral antigens in the patients' pancreatic tissue, she said. Nonetheless, the researchers are circumspect about the findings.

"We're not saying necessarily that this demonstrates that there's infection within these tissues, because we're seeing this after they've died. It could represent SARS-CoV-2 infection at a different site and then impacting the islet,” said Dr. Schwartz.

However, SARS-CoV-2 readily infected the investigators' cultured pancreatic cells in the laboratory, and caused a striking change in the beta cells, causing them to produce significantly less insulin and more glucagon. Glucagon, a hormone that makes blood sugar levels rise, is normally produced by pancreatic alpha cells to balance the glucose-lowering activity of the beta cells' insulin, so by switching from insulin production to glucagon production, the virally-infected beta cells were skewing that balance. These so-called polyhormonal cells are reminiscent of the pancreatic cells normally found in developing fetuses, as well as in very old patients and those with advanced type 2 diabetes.

"This phenomenon is not something that's broadly seen in other processes when people are sick," said Dr. Schwartz, who is also a hepatologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr. Schwartz is also on the scientific advisory board of Miromatrix Medical Inc. and is a paid consultant and speaker for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The findings raise several important new questions. First, the striking change in the pancreatic cells infected in the laboratory suggests that SARS-CoV-2 might have a range of other subtle effects. "When people talk about SARS-CoV-2 infection and how host cells respond, they talk about cell death," said Dr. Chen. "We found that actually the cell can change its identity."

She hopes to explore whether such transformative, but non-lethal effects persist over time, and whether they occur in other types of cells outside the pancreas. Second, the researchers are eager to study the clinical courses of patients who've survived COVID-19 infection, to see if the disease predisposes them to later problems.

"It raises the concern that a similar process could be occurring more broadly,” Dr. Schwartz said, “and I think the big question is, are we going to be seeing a big increase in the development of diabetes?"