To enable animals to shift their attention in response to changing circumstances, the prefrontal cortex of the brain helps keep track of which types of stimuli have recently been most relevant, suggests a preclinical study by Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian investigators. This discovery could lead to new treatments to help restore cognitive flexibility.

“Animals and people make split-second decisions about what to do in changing circumstances and what to pay attention to and what to ignore,” said lead author Dr. Timothy Spellman, instructor of neuroscience in psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Scientists know that the prefrontal cortex located in the front section of the brain is essential for this kind of cognitive flexibility because people and animals with injuries or illnesses that affect this brain region struggle to adapt in changing circumstances. Many scientists have hypothesized that the prefrontal cortex was acting like a filter telling the animal what to pay attention to and what to ignore. But in a study published in Cell on April 15, Dr. Spellman, senior author Dr. Conor Liston, associate professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, and others, show that the prefrontal cortex doesn’t kick in until after the fact.

“It is not acting like a filter on a moment-by-moment basis in decision-making,” said Dr. Spellman, who is also an instructor in neuroscience in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Instead, it seems to be playing a critical role after a decision is made and the animal has to evaluate whether the outcome was good in order to shape its next decision.”

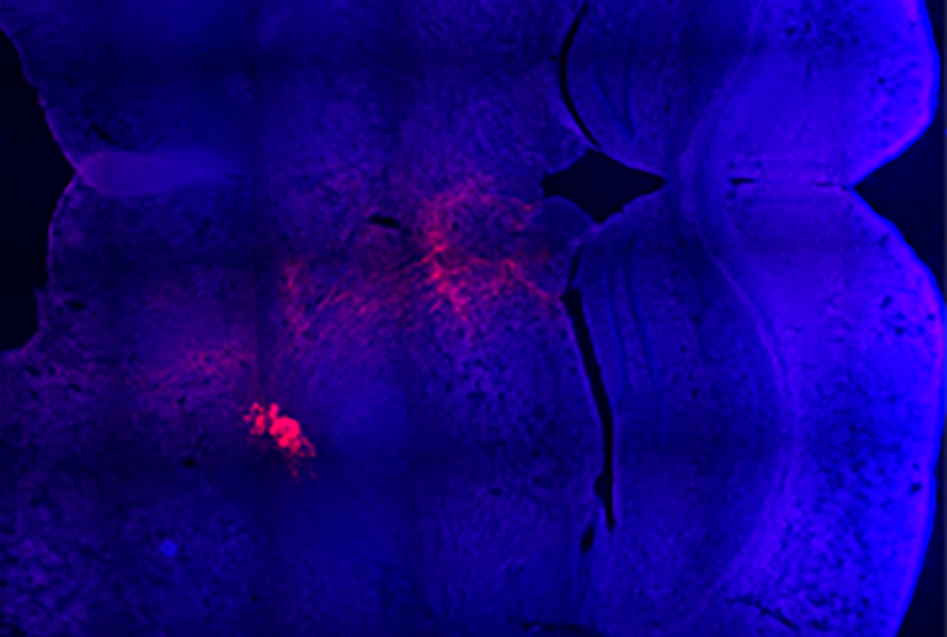

In the study, mice were trained to lick one of two spouts to receive a reward in response to an odor or a touch on their whiskers. Which spout they should lick in response to a particular stimulus was later changed, forcing the animals to adapt in order to get the reward. The team used a cutting-edge technique called 2-photon calcium imaging that allowed them to watch individual brain cells turn on and off while the mice completed the tasks. This allowed them to watch information flowing from cell-to-cell through the circuits of the brain in real-time, Dr. Spellman said, and revealed that prefrontal cortex cells weren’t essential during the decision-making task but rather after.

“The cells in the prefrontal cortex are acting as feedback monitors,” he said.

Next, they used a technique called optogenetics, which uses light to turn brain cells on and off. They found that turning off the prefrontal cortex cells mid-task did not affect the mice’s ability to perform the tasks but turning them off after task completion impaired their subsequent performance.

“This result was quite remarkable because it showed that prefrontal cells are required for supporting cognitive flexibility, but not in the way we expected,” said Dr. Conor Liston, who is also an associate professor of neuroscience in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute and a psychiatrist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “It shows that prefrontal cells play a critical role in regulating behavior by maintaining a memory of how recent decisions were paired with rewards.”

They also showed that rather than specific prefrontal cortex cells playing distinct roles in these tasks, there was a “gradient of information” with cells deeper in the prefrontal cortex processing more feedback information, Dr. Spellman said.

The discoveries may help scientists develop new treatments for psychiatric diseases like depression and schizophrenia, which impair cognitive flexibility.

“We currently don’t have good drugs to treat these kinds of cognitive symptoms,” Dr. Spellman said. “This new information may help us target drugs to cells in the prefrontal cortex to help restore cognitive flexibility.”