A molecule that helps prevent fat accumulation in mammals is produced within fat tissues by stem-like cells that may be therapeutic targets for obesity and related disorders, according to a new study from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Obesity has become a global pandemic in recent decades, and presently affects more than 90 million Americans and hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Obesity can be debilitating on its own, but it also increases the risk of other major diseases including cancers, heart disease, diabetes and immunological disorders.

One molecule of interest for anti-obesity strategies is the signaling protein interleukin-33 (IL-33), which, in mice, acts on immune cells within fat tissues to dampen inflammation and curb obesity during overfeeding. IL-33 is thought to have the same effect on humans, in whom lower blood levels of IL-33 have been linked to higher body weight. The principal source of beneficial IL-33 in fat tissues has been a mystery, but the investigators, in their study published May 3 in Science Immunology, identified that source as a population of immature, fat-resident cells called adipose stem and progenitor cells.

“We’ve known for years that IL-33 helps maintain a healthy immune system within fat tissues, but until now we haven’t known what cell type is chiefly responsible for this effect,” said Dr. David Artis, director of the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, director of the Friedman Center for Nutrition and Inflammation and the Michael Kors Professor of Immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Artis has been a paid Advisory Board member for the Kenneth Rainin Foundation, Food Allergy Research & Education, Pfizer, and MedImmune.

“Clearly more work is needed to determine precisely how to translate this discovery into clinical applications, but it could lead to better treatments for obesity and a host of other metabolic and immunological conditions,” he said.

In their study, Dr. Artis, who is also a professor in the Immunology and Microbial Pathogenesis program at the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences, and his team found that mice genetically engineered to lack the gene for IL-33 had immune abnormalities in their white fat tissue and accumulated much more white fat mass. By the age of 16 weeks, on a conventional diet, they averaged about 20 percent higher body weight than ordinary, wild-type mice.

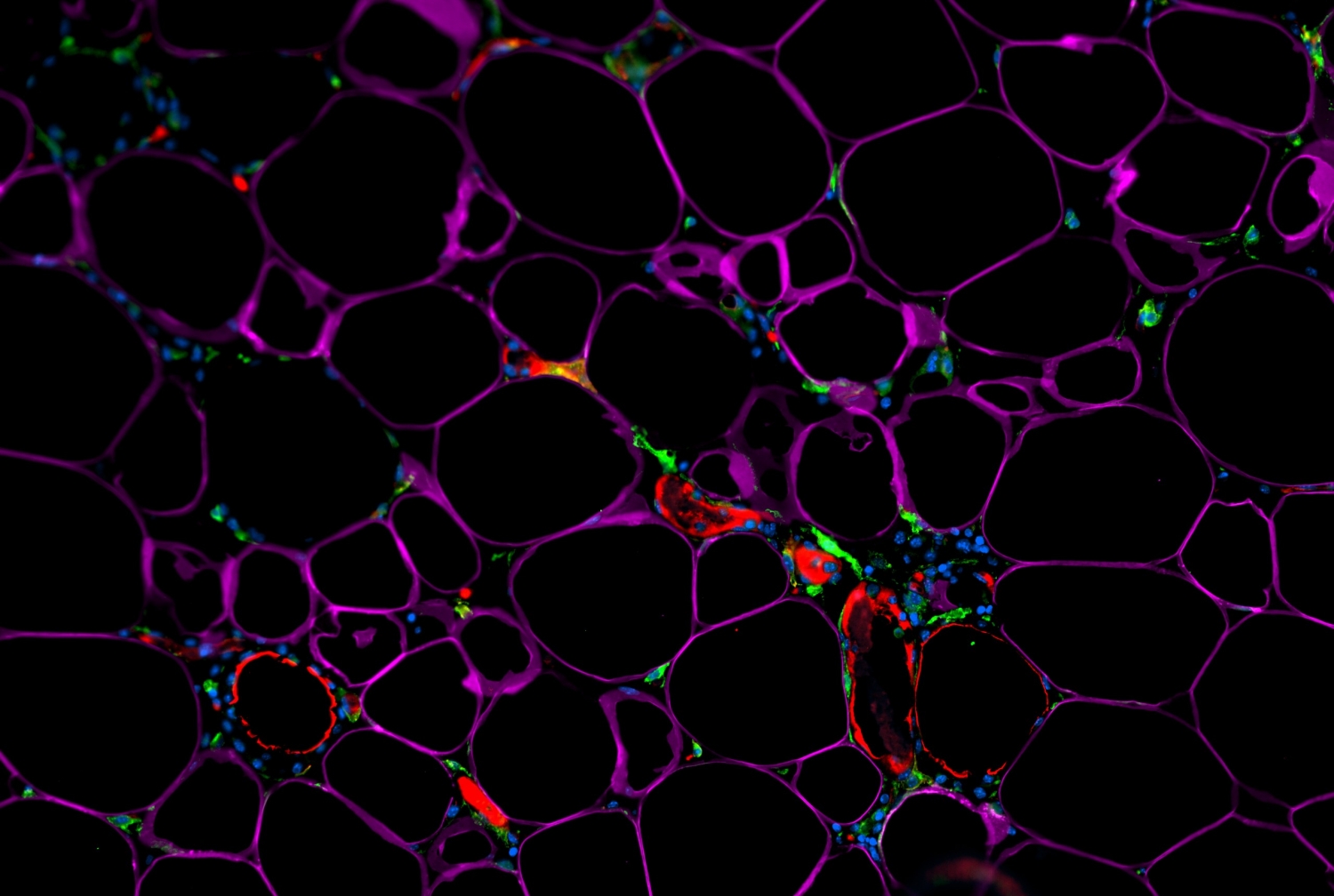

The scientists then analyzed the white fat of ordinary mice, separating out individual cell types within the fat, and ultimately determined that adipose stem and progenitor cells are the major IL-33 producers in these tissues.

Adipose stem and progenitor cells are immature cells that can give rise to fat cells and other mature cell types within fat tissue. Similar stem and progenitor cells reside in most other organs of the body, and are best known for keeping tissues in good repair by replacing cells that have died. The findings from Dr. Artis’ team suggest that these cells, within fat tissue, also play an important role in regulating immune pathways and fat storage. The experiments showed that IL-33 specifically from these cells promoted the activity of anti-inflammatory immune cells in white fat, and protected mice from weight gain after exposure to a high-fat diet. The team also found that a high-fat diet quickly reduced the cells’ production of IL-33, which suggests why IL-33 levels are lower in obese people.

Dr. Artis and his team are now continuing to study the IL-33-producing stem and progenitor cells, to understand better how to use them therapeutically, and how modern diet and lifestyle might be impairing their normal, beneficial functions.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, grants AI074878, AI095466, AI095608, AI102942 and AI106697; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mucosal Immunology Studies Team; the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation; Cure for IBD; the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; and the Rosanne H. Silbermann Foundation.