A rare inherited gene mutation predisposes people to developing a form of blood cancer called multiple myeloma, according to a new study by a multicenter research team led by Weill Cornell Medicine scientists.

The paper, published March 20 in Cancer Research, found that people with a mutation in a gene called lysine (K)-specific demethylase 1A, or KDM1A, had 6 to 9 times the risk of developing multiple myeloma. The research allows doctors to identify patients who are more likely to develop the disease, so that they can receive ongoing monitoring and treatment earlier in the course of disease, which correlates with better patient outcomes. A better understanding of this gene’s mutations and its role in multiple myeloma and other cancers including pediatric leukemia may also help scientists to develop new therapies.

“Myeloma patients who are treated early live longer and have better quality of life,” said lead study author Dr. Steven Lipkin, the Gladys and Roland Harriman Professor of Medicine and a professor of genetic medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. Those who are treated early also have a better chance of a cure, he added.

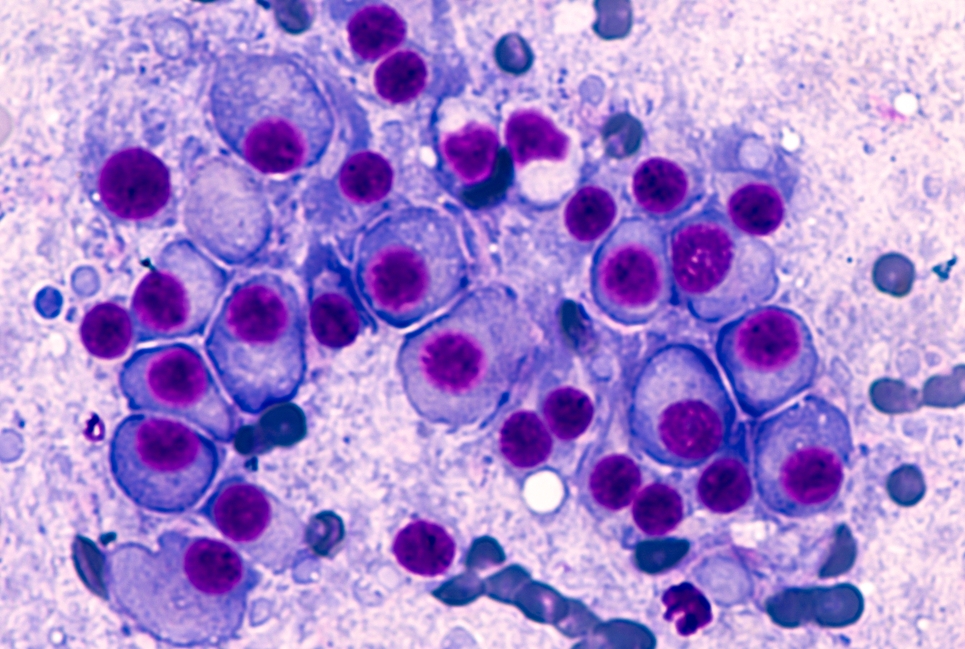

Multiple myeloma is the second most common cancer of the blood and is largely incurable, said Dr. Lipkin, who is also vice chair for basic and translational research in the Weill Department of Medicine, director of the Weill Cornell Cancer Genetics Clinic and a scientist in the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine. Some 30,000 people—most of whom will be older than 65—will be diagnosed with the disease this year. The cancer develops in the plasma cells, which are part of the immune system. Plasma cells arise from white blood cells called B lymphocytes, which are made in the bone marrow.

It has long been known that multiple myeloma runs in families. The disease—which is characterized by bone pain, weakness and fractures, and low blood counts, among other symptoms—was traditionally is usually thought to be caused by unknown environmental factors. However, Dr. Lipkin and one of the study’s co-authors, Dr. Ruben Niesvizky, a professor of medicine and director of the Multiple Myeloma Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, suspected that specific inherited gene mutations may also play a role in multiple myeloma.

“As a clinical geneticist, I typically see patients with a family history of cancer, including breast and colon cancer,” said Dr. Lipkin, who is also a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center and the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine. “But I’ve also seen some patients with several people in their family affected by multiple myeloma.”

For this study, the researchers evaluated the DNA in blood samples from 50 families with more than one person diagnosed with multiple myeloma. They used a technique called whole exome sequencing to analyze all of the genes that encode or provide instructions for making proteins to determine whether certain inherited mutations might be associated with multiple myeloma.

Through this analysis, followed by investigations in more than 1,000 additional patients, they found that a mutation in the gene KDM1A increases the risk of developing multiple myeloma six- to nine-fold. “We encountered this gene mutation and noticed that it seems to run in families,” Dr. Lipkin said. Looking at multiple myeloma patients with no family history of the disease, about 1 to 2 percent of people carry KDM1A mutations, he said.

The normal function of the KDM1A protein is to turn off and repress many genes that drive B lymphocytes in the immune system to grow and respond to infections. When KDM1A is mutated, genes important for B cell growth remain on, which may lead to uncontrolled proliferation and the development of multiple myeloma.

The researchers also studied the effects of KDM1A inactivation on B cells in mice. When treated with a drug that blocked KDM1A from turning off other genes, plasma cells grew in number and several genes that regulate cell growth were more active. This is consistent with a blood condition called monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), which can sometimes be a precursor to multiple myeloma.

The investigators hope these findings help scientists create genetic tests to screen patients for multiple myeloma risk, similar to the way women may be screened for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to see if they have an increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer.

“If we can identify people at risk of developing multiple myeloma, they could be monitored with blood tests for early signs of disease and treated sooner rather than later, resulting in better outcomes,” Dr. Lipkin said.

There are approximately 100 known cancer predisposition genes, and KDM1A is expected within the year to be added to commercial genetic testing panels and used in whole genome sequencing annotation.

Researchers may also be able to develop drugs that target KDM1A activity. Another group recently reported that FDA-approved drugs called Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors, which are already used for T cell lymphomas, may be particularly effective in killing cancer cells that have mutations in KDM1A. This could create a personalized treatment plan for multiple myeloma patients. “Our discovery of KDM1A,” he said, “could help with precision therapy for these patients.”