In spring 2013, Manhattan resident Jeri Bloome was 92 years old but had the energy of someone decades younger. She peppered her schedule with tugboat rides on the East River, strolls along the Brighton Beach boardwalk, lunches in Chinatown and visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art with her husband of more than half a century. Bloome was also enjoying the company of their only child, a daughter who had recently moved from Southern California into her parents’ spacious Upper East Side apartment—and had brought along her three perpetually hungry, early-rising cats.

A retired cosmetic buyer for a department store, Bloome was in superb health. So she and her husband were puzzled when, one evening, she spat up an ounce of blood. In the next few days, the couple consulted a bevy of specialists at Weill Cornell Medicine including a geriatrician, an ENT and two gastroenterologists. The culprit turned out to be a baseball-sized tumor that had ruptured through Bloome’s liver. “I had never been sick—really sick,” says Bloome. “Now, all of a sudden, I had liver cancer.”

Dr. David Madoff

Bloome’s outlook seemed dismal; her physicians predicted she had less than a year to live. Due to her advanced age and the particulars of her condition, she wasn’t a candidate for surgery or liver transplant—and because of the rupture, she wasn’t able to try other treatments. Then Dr. David Madoff, a professor of radiology and vice chairman for academic affairs at Weill Cornell Medicine, offered her new hope: radioembolization, a nonsurgical procedure that targets liver tumors with radioactivity delivered through the arteries. While more than 20,000 people in the United States have been treated with radioembolization since the FDA approved it in 1999, Dr. Madoff says that when he performed the procedure on Bloome in April 2013, she was the first patient with prior tumor rupture ever to undergo it. The treatment—which was so minimally invasive that Bloome walked home later that day—was successful, and four and a half years later she remains cancer free. “The procedure was amazing—I didn’t suffer at all,” she says, adding, “Dr. Madoff saved my life.”

More than 700,000 people worldwide are diagnosed with primary or metastatic liver cancer each year. In the United States, about 40,700 new cases of the disease will be detected in 2017, according to the American Cancer Society—and the incidence has been on the rise, more than tripling since 1980. This is partially due to a high rate of a key risk factor for liver cancer—hepatitis C virus—among Baby Boomers, suggests a recent report published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Soaring rates of obesity and type II diabetes have likely contributed to the increase as well.

Rupture, though rare, is one of the most life-threatening conditions linked to liver cancer. As many as 67 percent of patients die within thirty days of the organ rupturing, according to a paper that Dr. Madoff and colleagues published in the January/February 2016 issue of Clinical Imaging. Survival depends on age, overall liver function, the extent of the disease and presence of other conditions such as cirrhosis—liver damage that can be caused by, for example, excessive alcohol consumption or hepatitis. “When a tumor ruptures, it can spread outside the liver,” says Dr. Madoff, an attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, “which is obviously a very, very bad thing.”

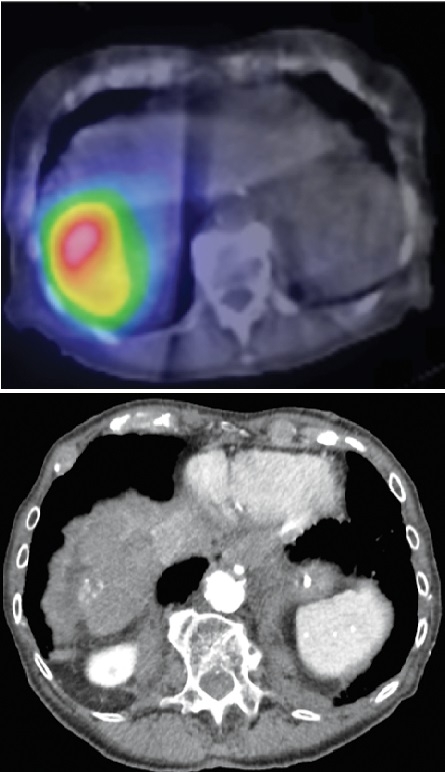

Imaging after Bloome’s procedure (top) shows radioactivity at the site of her tumor; (left) four years after the treatment, only a small area of calcification remained. Opposite page: Bloome (right) at home during her twice-weekly physical therapy session. Photo provided

Radioembolization is a two-step procedure typically performed under moderate sedation, with the patient remaining semi-conscious. An interventional radiologist first inserts a catheter into an artery through the patient’s groin and threads it toward the liver. After examining the labyrinth of arteries that supply blood to the liver and tumor, the physician injects the vessels with a tiny, harmless dose of radioactivity to see if it stays inside the liver and does not spill into the bowel or lungs. If the test run reveals no spillage, the patient is approved for the actual treatment, which occurs about a week later. Then, a much higher dose of radioactive particles is placed inside the blood vessels feeding the tumor. They embed themselves in the tumor and irradiate it from the inside out, sparing surrounding tissue.

Because Bloome’s tumor and liver capsule were not intact, potential spillage of the particles—which in large amounts could theoretically inflame the abdomen’s inner lining—particularly concerned her doctors. But the test run showed no leaks, so Dr. Madoff went through with the main procedure, a decision bolstered by Bloome’s overall vitality and enthusiasm for the treatment. Says Bloome: “I just had confidence that he was going to cure me.” She and her husband, Marc—a World War II veteran and entrepreneur who accompanies his wife to every doctor’s appointment and knows the smallest details of her medical history—appreciated Dr. Madoff’s can-do approach. “A problem and a solution were presented to us at the same time,” says Marc Bloome. “And of course we had to go for it.” Dr. Madoff has been monitoring Bloome—who is now 97—with CT scans to make sure the cancer isn’t coming back, something that he considers unlikely. “This case,” he says, “is one where I would say that we completely cured the patient of a potentially incurable disease.”

Bloome soon returned to her active lifestyle—doing strength and balance training twice a week, going to Broadway shows, dining at her favorite French restaurant and taking long walks with her husband. In short, she says, “I feel wonderful.”

— Agata Blaszczak-Boxe

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Vol. 16. No. 3