Ovarian tumors can be made more sensitive to immunotherapy by blocking the recruitment of certain cells to the area surrounding the cancer, according to preclinical research by investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine.

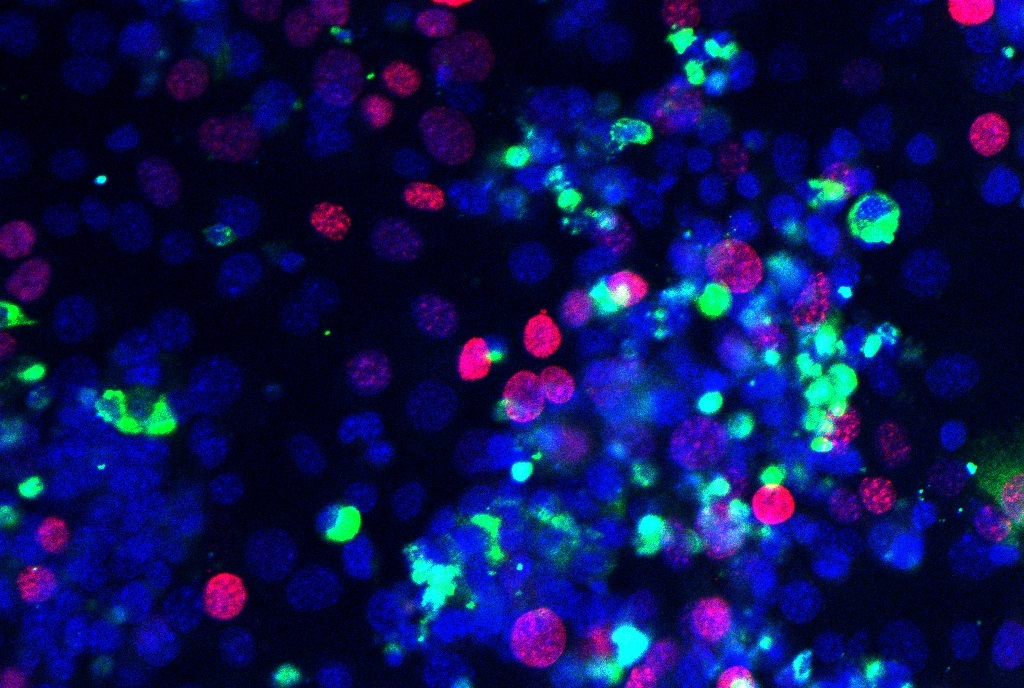

Unlike some other solid tumors, including lung cancer and melanoma, ovarian cancer generally does not respond to immunotherapy. In a study published Dec. 8 in Nature Communications, researchers looked at the role of a protein called UBR5, which is found at high levels, or amplified, in particularly aggressive cases of ovarian cancer. They found that UBR5 draws in immune cells called macrophages to the area around the tumor known as the tumor microenvironment, which protect the cancer cells. Furthermore, when they blocked UBR5 in tumors in animal models, they were able to destroy previously resistant tumors with two different forms of immunotherapy as well as chemotherapy.

“Clinical data show that amplification of UBR5 in the tumor is associated with significantly shorter survival times in patients with ovarian cancer,” said senior author Dr. Xiaojing Ma, professor of microbiology and immunology and of microbiology and immunology in pediatrics. “Our studies in the lab found that this is the case because UBR5 allows the cancer cells to send out signals that bring in macrophages. These macrophages, in turn, promote cancer growth and spread by providing essential nourishment and suppressing the immune system.”

In earlier work, Dr. Ma and his team identified UBR5 as an important factor in making triple negative breast cancers more aggressive. (Triple-negative breast cancers lack a receptor called HER2 and receptors for estrogen and progesterone, three factors that can be targeted with drugs.) In animals that had no immune systems, higher levels of UBR5 did not affect the aggressiveness of the cancer, suggesting that UBR5 was acting through the immune system. In the case of breast cancer, the researchers found that UBR5 inhibits the activation of immune cells called CD8 T cells in the tumor microenvironment.

In the current study, the researchers showed that when UBR5 was blocked in animal models of ovarian cancer, it prevented the cancer cells from bringing in protective macrophages. Those animals responded well to two types of immunotherapy: immune checkpoint blockade with an antibody that blocks PD-1, which takes the brakes off the immune system and allows it to attack cancer cells, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T therapy, in which T cells are engineered to seek out and destroy cancer. In this study, the CAR T cells were engineered to detect a protein called MUC16, which is common in many ovarian cancers. The tumors were also much more sensitive to the chemotherapy drug cisplatin.

While the research demonstrates that UBR5 is a promising target for cancer therapy, there is not yet a drug that can be used to block UBR5 in humans. Thus, Dr. Ma is working with researchers in the Tri-Institutional Therapeutics Discovery Institute of Weill Cornell Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and The Rockefeller University to develop a compound that could eventually be tested in clinical trials, in combination with checkpoint inhibitor drugs, CAR T treatments, or chemotherapy.

“Our research is focused on breast cancer and ovarian cancer, but amplification of UBR5 has been found in many other types of cancer as well,” said Dr. Ma, who is also a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center. “If found, such a drug could be useful in developing combination treatments for a range of cancers that resist treatment because of high levels of UBR5.”