By Heather Salerno

In many ways, breast cancer doesn’t discriminate. It strikes young and old, rich and poor, women and men—people from all walks of life. Yet for Dr. Lisa Newman it’s long been clear that the disease isn’t an equal-opportunity illness. When Dr. Newman was starting out as a general surgeon in Brooklyn in the 90s, she started to notice something unusual among the African American women who were coming to her after being diagnosed. They were often younger than her white patients, and usually had tumors that were harder to treat.

This pattern of disparities inspired Dr. Newman to start looking into its causes, and since then she has become an internationally renowned surgical oncologist and breast cancer researcher who has spearheaded groundbreaking studies that strive to understand how the condition varies by race and ethnicity.

Dr. Lisa Newman. Credit: John Abbott

She was appointed chief of the Section of Breast Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and Weill Cornell Medicine in August 2018, having been recruited from the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit. In addition to her clinical work leading the Breast Surgical Oncology Programs for NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and Weill Cornell Medicine, Dr. Newman is the founding medical director of the International Center for the Study of Breast Cancer Subtypes (ICSBCS), where she and other Weill Cornell Medicine researchers—like molecular geneticist Dr. Melissa Davis, an associate professor of cell and developmental biology research in surgery—are largely focused on investigating genetic links between African ancestry and a higher incidence of aggressive tumors in African American women, including triple-negative breast cancer, a difficult to treat form of the disease that accounts for 15 to 20 % of all breast cancer cases in the United States.

It’s an issue that hits home for both Drs. Newman and Davis, who are African American and among the few women of color working in this field. Dr. Davis says new therapies can’t come soon enough for the black women in her life who she sees fighting the disease every day: a teacher at her child’s school, other mothers in her neighborhood, fellow churchgoers. “One of my classmates from high school died of breast cancer, right after she had her first daughter,” she says. “These women aren’t grandmothers in their 60s—they’re active women with young kids. These are tragic stories, and it’s what compels me to continue doing what I’m doing.”

An Unequal Burden

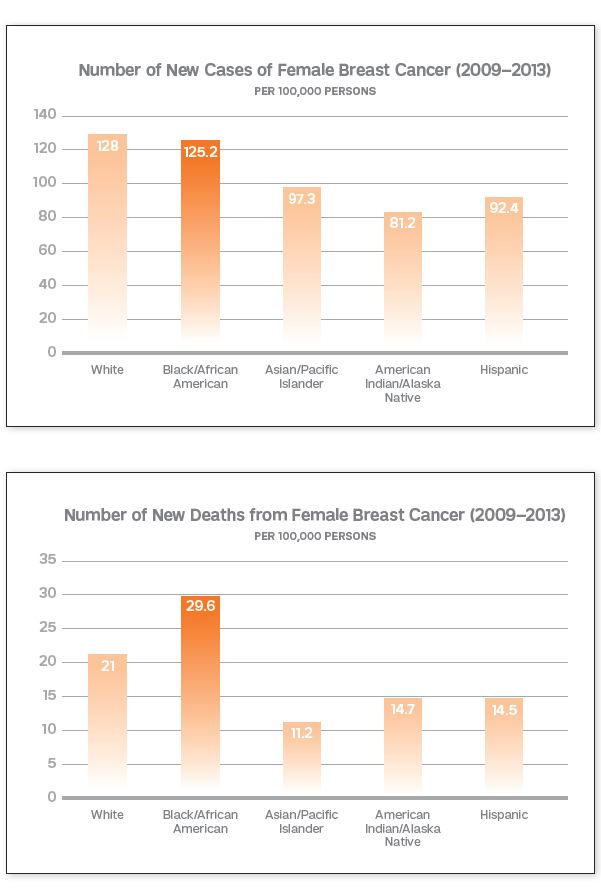

About one in eight U.S. women—or about 12 %—will develop breast cancer in her lifetime, with an estimated 268,600 new cases expected to be diagnosed in 2019 alone. There’s good news, though: according to the American Cancer Society, overall deaths from breast cancer have dropped significantly over the last 30 years, due to increased awareness, early diagnosis and improved treatments. Its incidence has risen across all races and ethnicities since the 80s—mostly because of increased detection by mammography—though the condition occurs less frequently in Asian, Hispanic and Native American women than in white or African American women. Yet incidence rates have mostly stabilized for white women in recent years, while rates for African American women have continued to rise. And for women under 45, breast cancer is seen much more often in African Americans than in Caucasians.

Most significantly, black women have the highest breast cancer mortality of any racial or ethnic group in the country—shockingly, 42 % higher compared to white women. That figure has so worried the medical community that the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging updated its screening guidelines last year: for the first time, the organizations added black women to the list of groups considered to be high-risk. “All women, especially black women and those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, should be evaluated for breast cancer risk no later than age 30,” the experts wrote, “so that those at higher risk can be identified and can benefit from supplemental screening.”

Contributing to this gap are socioeconomic challenges faced by the African American community, such as higher poverty rates, a greater likelihood of being underinsured, and a lack of access to timely diagnostic tests, treatments and other services. But doctors like Dr. Newman have long thought that genetic differences also play a role. She and her ICSBCS team have therefore developed a field of research they named “oncologic anthropology,” which looks at genetic features associated with race/ethnicity and population migratory patterns that might predispose certain women to a higher or lower breast cancer risk. For example, Dr. Newman wondered why African American women are twice as likely as white women to have the disease’s triple-negative form, so named because it lacks the three most common receptors known to fuel most breast cancer growth: estrogen, progesterone and the HER2/neu gene. That means drugs aimed at those receptors, like hormone therapy, are less effective. “Unfortunately, we don’t yet have targeted therapies for these triple-negative tumors,” says Dr. Newman, “and they also tend to be more virulent.” As a result, patients have a poorer prognosis, which could contribute to the disproportionate death rate among African Americans.

Charts based on figures from the National Cancer Institute show the clear racial disparities between breast cancer diagnoses (top) and deaths. Credit: American Cancer Society Action Network, Enhanced by Jennifer Kloiber Infante

Global Outreach

It bothered Dr. Newman that more hadn’t been done to investigate racial disparities associated with triple-negative breast cancer, and she suspected the differences might have something to do with African ancestry. So in 2004, when she was head of the University of Michigan Breast Care Center, she reached out to the Komfo Anoyke Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana a West African country where more than half of all breast cancers are triple-negative. Dr. Newman offered mentorship and other resources to the medically underserved nation and began traveling to Ghana several times a year with medical students, trainees and fellow physicians, bringing supplies and helping to evaluate and treat patients there—a collaboration that she continues through Weill Cornell Medicine in Ghana and other sites throughout Africa. She established a telemedicine service that allows African clinicians to confer with American colleagues, along with a core biopsy training program so breast cancers can be diagnosed more efficiently. She also set up opportunities for Ghanaian hospital staff to come to the United States for training in cutting-edge surgical and pathology techniques. As a result, Dr. Newman says, “I’ve been really happy to see that our international partnership has led to improved care for patients.”

International Partnership: Dr. Newman (center) and Dr. Davis (third from right) in Ghana, where they’ve conducted research and Dr. Newman has done clinical work. Photo provided

The ICSBCS features a biorepository for tissue and DNA samples gathered from Ghanaian breast cancer patients to be used in genetic studies. After comparing those specimens collected from African Americans and white Americans, Dr. Newman saw similar patterns of aggressive disease among the African Americans and Ghanaians, which suggested a strong hereditary component. Additional research backed up that theory: African Americans showed fewer similarities in breast cancer patterns when compared to women from the eastern African nation of Ethiopia, where the frequency of triple-negative breast cancer is relatively low. Dr. Newman believes this supports the idea that triple-negative status among African American breast cancer patients is strongly associated with hereditary susceptibility—with Western Sub-Saharan African ancestry appearing to be a crucial element. This makes sense, she adds, given the history of the global slave trade. Most black women born in the United States are likely descendants of West Africans who were enslaved and brought to North America and the Caribbean several centuries ago; East African slaves, on the other hand, were typically brought to the Middle East and Asia. “Contemporary African Americans therefore have more shared ancestry with Ghanaians than with East Africans,” she explains.

Dr. Davis started collaborating with Dr. Newman on this part of her research in 2016, when she was recruited to join Dr. Newman’s team in Detroit—though she’d known of her work for at least a decade before that. Now Dr. Davis, who joined the Weill Cornell Medicine faculty in fall 2018, serves as ICSBCS’ scientific director. Most recently, the two co-authored a study that was published in April in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, which examined a gene mutation that originated in Sub-Saharan Africa and may help explain why black women have worse breast cancer outcomes. This gene, DARC/ ACKR1—also known as the Duffy gene—plays a pivotal role in immune regulation; when acting normally, it seems to control systemic or circulating signals of inflammation, which has long been connected to cancer growth. Over time, however, a mutation called “Duffy null” evolved in the West African population; it removes the expression of the gene in red blood cells and may alter expression in other tissues in the body. This gene alteration protects carriers against malaria, a life-threatening, mosquito-borne disease that is widespread in the Sub-Saharan region. Though it’s helpful in staving off that illness, the mutation—which is present in nearly all West Africans and between 50 to 75 % of African Americans—seems to have a detrimental effect when it comes to cancer.

Dr. Melissa Davis. Credit: John Abbott

For their study, Drs. Davis, Newman, and colleagues scrutinized tumor tissue and other genomics data from breast cancer patients from around the United States and found that tumors from African Americans on average had lower expression levels of the Duffy gene when compared to white patients. Lower levels were then linked to more aggressive tumor types while higher levels were associated with significantly longer survival. “For the first time,” says Dr. Davis, “this shows a mechanism of why tumors are more aggressive or harder to treat in people of West African ancestry.” She’s continuing to build on these results, in the hope that it will lead to new ways to approach the disease. Ideally, she says, “I’d like doctors to be able to say to a patient, ‘If you have this mutation and you develop a tumor, you will have a certain type of immune response. Therefore, here’s what your first line of treatment should involve.’ ”

Targeted Approaches

For Dr. Olivier Elemento, director of the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine and associate program director of the Clinical and Translational Science Center—who is helping Dr. Newman, Dr. Davis and their colleagues examine DNA samples from breast cancer survivors in the United States, Africa and elsewhere—such efforts are an example of how analyzing cancer genomes can assist physicians in optimizing treatment for individual patients, something that is especially important for those who belong to an often-overlooked minority group. For instance, Dr. Newman’s breast team works with the institute to interpret genetic tests performed on patients with metastatic breast cancer, the most advanced stage of the illness. Information gathered from such tests—such as whether a tumor will likely respond to chemotherapy or novel targeted treatments—helps guide doctors on the best course of action for individual patients. Dr. Elemento says research like Dr. Newman’s may also help scientists discover more about the origins of breast cancer, leading to the advancement of new therapies that could aid a wider patient population.

Raising Awareness: Dr. Newman talking with attendees at a June event at Riverside Church, co-hosted by Susan G Komen Greater New York City.

Dr. Davis points out that part of the problem in addressing these disparities—and, in turn, finding more effective medications to improve outcomes—is that minorities haven’t traditionally been included in adequate numbers in research studies or clinical trials. “A lot of breast cancer investigations that have resulted in advances in treatment have overwhelmingly involved white women,” she says. “So the treatments work better in those populations than in others. We’re trying to change that.” Dr. Elemento agrees, noting that recruiting a more diverse patient cohort for precision medicine studies and trials is a priority for the Englander Institute in the coming years. “We need to ensure that all patients benefit equally,” he says.

Breast cancer survivors like Mary Waters are trying to do their part as well. The 63-year-old former Michigan state representative is a past president of the Detroit chapter of the Sisters Network, a national African American breast cancer survivor advocacy organization where Dr. Newman serves as chief medical adviser. Waters met Dr. Newman in 2009, not long after being diagnosed with Stage 2 breast cancer and joining the organization, and was immediately impressed with the physician’s deep commitment to the cause. She helped recruit volunteers for Dr. Newman’s research through network meetings and allowed her own DNA samples and medical records to be included in the ICSBCS registry. Waters says it can sometimes be difficult to convince African Americans to participate in such efforts; there is still a lingering mistrust of medical research among many that dates back to the Tuskegee study, as well as a cultural inclination to stay quiet about health problems. “But this is about staying alive,” says Waters, “and we have to do whatever we can to help.”

That also means increasing outreach so more black women know about their breast cancer risk and how to seek preventive care. In Detroit, Dr. Newman aided the Sisters Network chapter with its annual Gift of Life Block Walk, where members knock on doors in predominantly African American neighborhoods to talk to residents about breast cancer awareness. She’s been involved with similar efforts since arriving in New York: in June, Dr. Newman spoke about her research at a senior center in Brooklyn, and later in the month at a brunch co-hosted by Susan G. Komen Greater New York City. The goal of the community event, held at Riverside Church in Morningside Heights, was to motivate African American women to get screened. Addressing disparities among African Americans is a top priority for the Komen organization, which has funded some of Dr. Newman’s research. (She is also an advisory board member for the group.) Komen NYC CEO Linda Tantawi says it’s important for black women to see and hear an African American physician-scientist like Dr. Newman; it builds their trust in the healthcare system and urges them to do whatever they can to fight the disease. The strategy is working: Dr. Newman says that after her talks, women often tell her that she has inspired them to get their first mammogram or see a doctor about a potentially cancerous lump. “Hearing from someone like Dr. Newman, and seeing how much she cares, encourages these women to care about themselves and others in the community,” says Tantawi. “And every person at that brunch probably told ten people about what they heard.”

An attentive crowd listens to Dr. Newman’s remarks.

Moving forward, Drs. Newman, Davis, and the rest of her team will expand on their genetic studies of African Americans. They also plan to look at other minority groups: they want to learn why breast cancer incidence and mortality rates are lower for Latinas in the United States compared to African Americans and white Americans. Recent research—similar to the work that ICSBCS has been conducting related to African ancestry—has found that a higher proportion of indigenous American ancestry in Latinas tends to reduce their likelihood of developing breast cancer. The ICSBCS group is currently developing a partnership with a team of breast cancer specialists in Mexico to further explore the topic. “This type of research has broad implications,” says Dr. Newman. “If we can figure out comprehensively how genetic factors are related to the causes of breast cancer, that will be useful information for everyone.”

Dr. Elemento is the co-founder and equity holder for Volastra Therapeutics Inc. and OneThree Biotech LLC. Both companies focus on technologies related to precision medicine.

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Summer 2019