Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, is the fourth-leading cause of death worldwide. And as the population ages, rates are rising: while there were an estimated 227 million cases in 1990, by 2010 that number had reached 384 million. But studies suggest that as many as 70 percent of people who have COPD—a generally progressive disease with lung inflammation and scarring—go undiagnosed, and therefore miss out on treatments that can improve quality of life and potentially slow the progress of this still-incurable disease. “If we can find these undiagnosed patients, we think we’ll be able to have a major beneficial impact for them and for the healthcare system,” says COPD expert Dr. Fernando Martinez, chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, who has spent much of his 30-year career caring for COPD patients, investigating new methods of identifying patients at risk for the disease, and developing new treatments for it. “There are multiple therapies now available that improve quality of life and reduce shortness of breath, acute events, emergency department visits and mortality.”

Why are so few people diagnosed? For one thing, Dr. Martinez says, sufferers tend to be older, and they and their doctors may blame symptoms like shortness of breath on normal aging. And there are lingering misconceptions about the disease’s demographics. Although women are actually more likely to die of COPD, it’s still largely considered a man’s disease—and while tobacco use remains the primary cause, a quarter of COPD patients have never smoked.

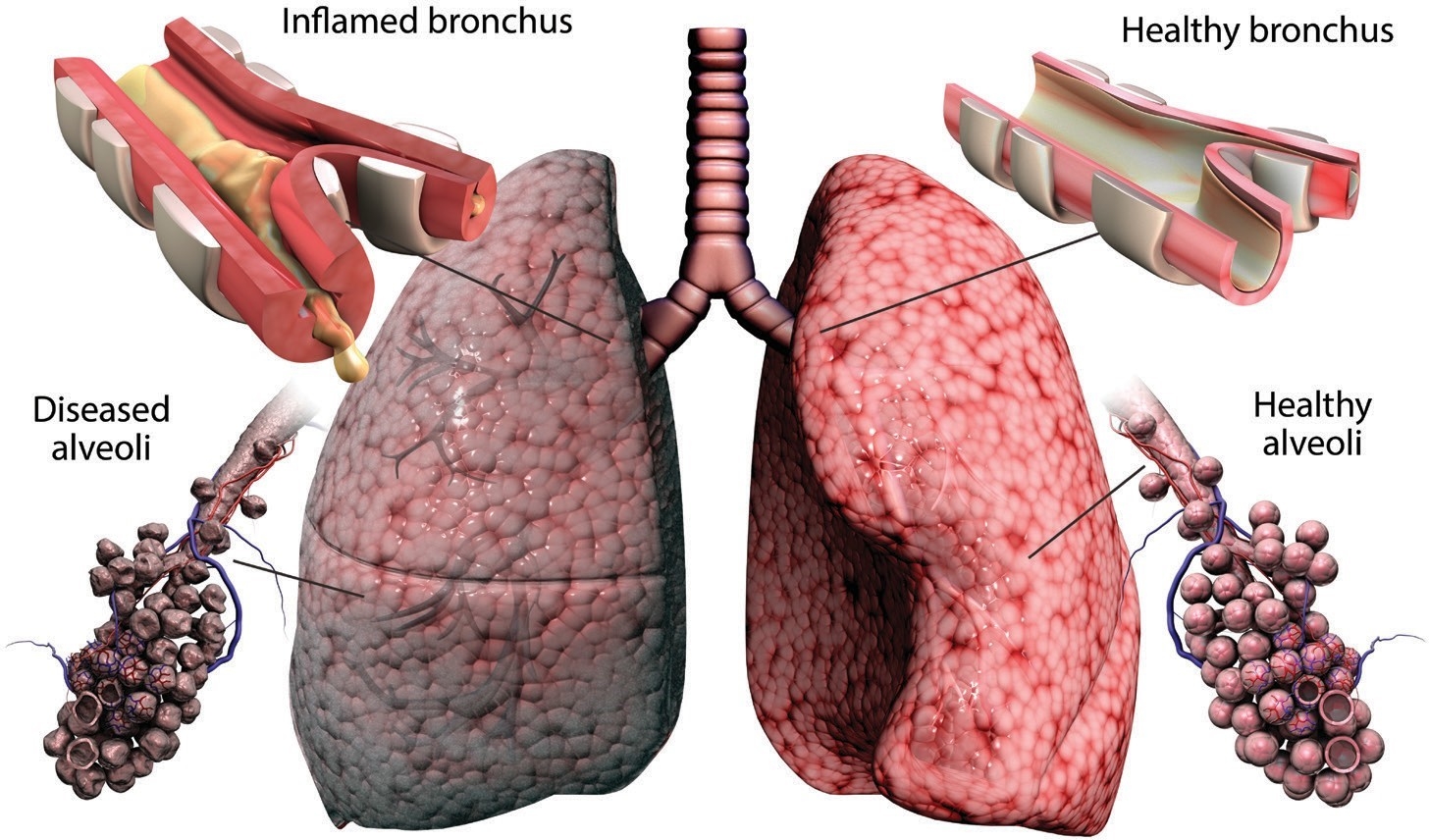

BREATHING PROBLEMS: An illustration of a lung with (left) and without COPD. Photo: Gunilla Elam/Science Photo Library

But, Dr. Martinez says, the key to getting more people diagnosed and treated may simply be a matter of asking the right questions. So with colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine, the University of Michigan and other institutions, he developed a simple screening instrument called the COPD Assessment in Primary Care to Identify Undiagnosed Respiratory Disease and Exacerbation Risk (abbreviated as “CAPTURE”) that may prove revolutionary. Preliminary data from small trials in physicians’ offices—which involved a total of about 350 patients and control subjects at six locations across the United States—indicate it is much more effective than current screening methods, and Dr. Martinez and his colleagues recently received a grant from the NIH to test it more widely. “CAPTURE was developed in partnership with patients,” Dr. Martinez says. “We asked them, ‘What are the questions that you think we should be asking? How should we ask them?’ Eventually, we came up with this very simple set of five carefully worded questions, some of which I would never have thought to ask.”

The CAPTURE questions are: Have you ever lived or worked in a place with dirty or polluted air, smoke, second-hand smoke or dust? Does your breathing change with seasons, weather or air quality? Does your breathing make it difficult to do things such as carry heavy loads, shovel dirt or snow, jog, play tennis or swim? Compared to others your age, do you tire easily? In the past 12 months, how many times did you miss work, school or other activities due to a cold, bronchitis or pneumonia? A score is calculated, with a point for each affirmative answer to the first four questions added to the number of missed events reported in the fifth question. Fewer than two points indicates that a patient probably does not have COPD; between two and four should be followed up with a basic measure of pulmonary function, known as a peak flow test. A patient who does poorly on the peak flow measure, or who scores five or more on the questionnaire, will receive further clinical evaluation, including a test known as spirometry, which may lead to a formal diagnosis.

In developing the questionnaire, Dr. Martinez and his colleagues studied whether certain questions were more likely to indicate that a given patient had COPD. Surprisingly, they found that those that focused too heavily on a person’s smoking history—asking how many packs a day they smoked, for example—proved less relevant than more general inquiries about exposure to environmental contaminants. Asking patients about whether breathing problems made specific activities difficult was more likely to identify COPD than simply asking whether a patient ever experiences shortness of breath; after all, most people get breathless when they exercise vigorously. And asking them to compare themselves with their peers helps control for the fact that COPD symptoms may be confused with normal aging. “This questionnaire,” he says, “has addressed those potential initial biases that we all have.”

Originally published in 2016, CAPTURE has been translated into 14 languages and is being used in academic studies around the world. Dr. Martinez now wants to know how it will work with a large, diverse population, so the new study will involve 5,000 patients in one hundred primary care centers around the country, in a variety of communities (such as those that are urban, rural, wealthy or economically disadvantaged). Another goal of the study is to determine whether primary care doctors are willing to take the extra five to 10 minutes per office visit to administer the questionnaire. Finally, the new study will seek to determine whether CAPTURE helps more patients access treatments that improve their quality of life. In addition to new medicines that can lessen symptoms and improve quality of life, patients may benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation therapy and other nonmedical treatments. And in the future, Dr. Martinez hopes physicians will be able to intervene even sooner: he is planning a new study to develop better ways of finding patients as young as their 30s and 40s who are at risk for developing COPD.

For Dr. Martinez, the fight against COPD is driven by more than a professional passion. A close relative, who’s now 80, has suffered for years from severe COPD, which has significantly affected his quality of life. “He was a man who always seemed to be in charge of everything—a wonderful guy, but you look at him now and he’s like a shadow of himself,” Dr. Martinez says. “It’s sad, and it’s something my family deals with every day. So I have a personal stake in helping others to avoid going down that path.”

— Amy Crawford

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Winter 2019