Weill Cornell Medicine has been awarded a five-year, $4.2 million grant by the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which immune cells called B cells interact with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) to cause lymphoma, particularly in people living with HIV. The funding will support projects that began with a grant awarded by the Starr Cancer Consortium.

EBV infects over 90 percent of the population, and the infection can be lifelong as the virus remains within cells in a dormant state called latency. When the virus is in this tight latent stage, it is hidden from the immune response. However, through a poorly understood mechanism, the virus can begin making additional viral proteins that can induce cancers, including diffuse large B cell lymphoma, a type of blood cancer. This tendency is much higher in people living with HIV. In EBV-associated cancers, the amount and type of viral proteins made are variable, and affect how the immune system recognizes the infected tumor cells.

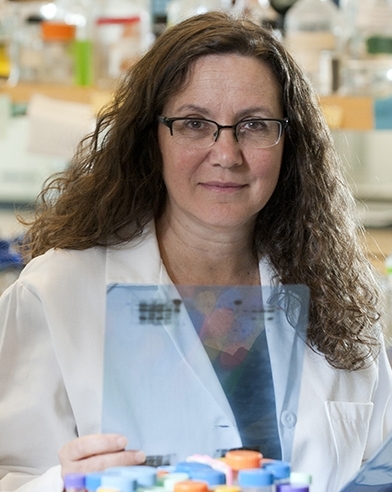

Dr. Ethel Cesarman

“There are several cancers that are increased with people who have HIV, and one of those cancers is lymphoma,” said principal investigator Dr. Ethel Cesarman, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Amongst those lymphoma cases, about 30 percent are caused by EBV. In people without HIV, it’s less than five percent.”

Even among individuals receiving antiretroviral therapies to suppress HIV infection, EBV-associated lymphoma occurs at a significantly higher frequency.

“You can think of infection by Epstein-Barr Virus as being an opportunistic cause of cancer,” said Dr. Cesarman. “But even with good control of HIV and an apparently normal immune response, there are still more of these cancers in people living with HIV than in the general population.”

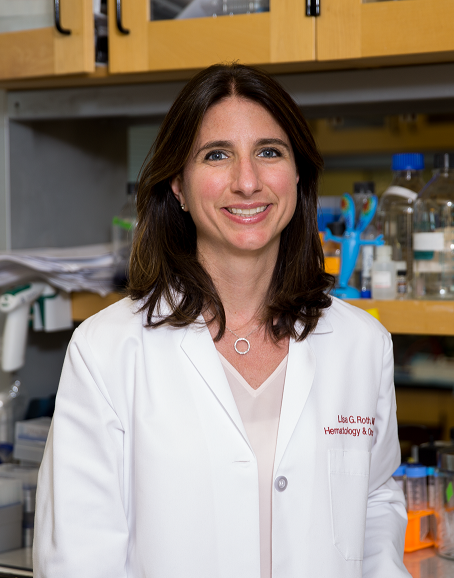

With the current grant, Dr. Cesarman and co-PI Dr. Lisa Giulino Roth, associate professor of pediatrics, will examine which EBV genes and proteins are expressed in diffuse large B cell lymphomas, which occurs in B cells in the late stages of the immunological life cycle, after an immune response has occurred.

Dr. Lisa Giulino Roth

The proposed projects build on research using CRISPR and chemical genetic analysis that was conducted by the lab of co-PI Dr. Ben Gewurz, associate professor of medicine and associate head of the virology program at Harvard Medical School and an infectious diseases specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Those analyses identified host DNA and histone methyltransferases, which regulate gene expression in a process called epigenetic control, as having an important role in EBV latency.

“We’re trying to see how the virus escapes recognition by the immune response at the molecular level,” said Dr. Cesarman.

“A better understanding of how EBV controls latency proteins will help us to develop therapies that could allow the immune system to attack these lymphomas,” explained Dr. Roth.

In addition, because incidences of EBV-associated lymphomas have been noted to be high in Mexico, the investigators will be working with the Salvador Zubirán National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition in Mexico City to build a lymphoma tissue bank to study the pathology in people living with HIV.

“We think that we will learn more about the virus biology and that can have implications for a potential immunotherapy for these patients,” said Dr. Cesarman.