Melanoma cells release small extracellular packages containing the protein nerve growth factor receptor, which primes nearby lymph nodes for tumor metastases, according to a new study by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators.

The study results, published on Nov. 25 in Nature Cancer, may one day help doctors determine which patients need more aggressive treatment and could help with the development of new therapies, said senior author, Dr. David Lyden, the Stavros S. Niarchos Professor in Pediatric Cardiology and a professor of pediatrics and of cell and developmental biology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Traditionally, scientists have had a tumor-centric view of melanoma in which cells from the tumor break off and travel to nearby lymph nodes, as cancer metastasizes. “What our study shows is that the lymph node functionally prepares for future metastases,” said Dr. Lyden, who is also a member of the Gale and Ira Drukier Institute for Children’s Health and the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. “There are many changes taking place in the lymph node even before the tumor cell gets there. We call it a pre-metastatic lymph node.”

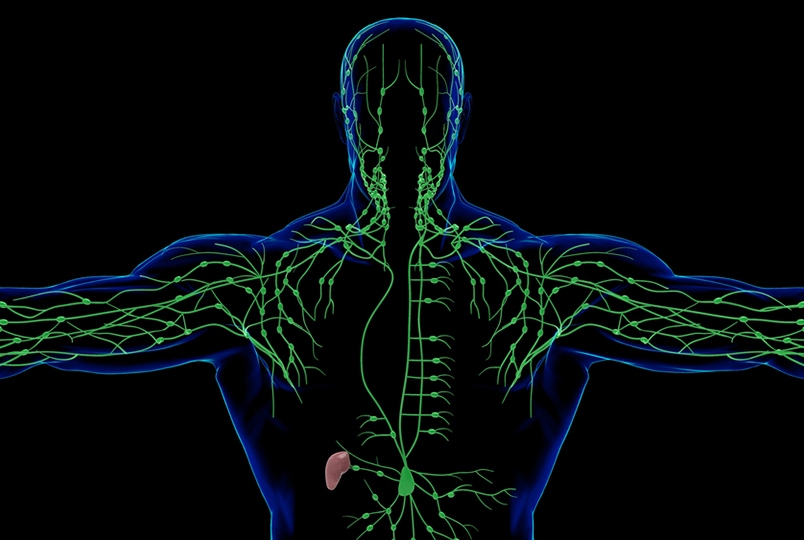

Using mouse models, lead author Dr. Héctor Peinado, head of the Microenvironment and Metastasis Laboratory, Molecular Oncology Program at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, examined the release of exosomes from melanoma tumor cells. Exosomes, also called extracellular vesicles, are small packages containing various particles and proteins that are secreted by cells and travel through lymph vessels and blood to distant sites where they can be taken up by other cells.

Dr. Peinado, who was previously a postdoctoral associate and assistant professor along with co-first author Dr. Alberto Benito Matin, a former postdoctoral associate in Dr. Lyden’s lab, where this work began, found that the nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) protein is released in exosomes secreted by melanoma cells and carried into the lymph nodes. The protein is then taken up by lymph endothelial cells, or cells lining the lymph vessels, where it reprograms the lymph node to form new lymph vessels. This process, called lymphangiogenesis, encourages cancer spread. “The more vessels a lymph node has, the more tumor cells can enter,” Dr. Lyden said.

Lymphatic endothelial cells are the first encounter for exosomes containing NGFR and “open the gates to melanoma cells coming into the lymph node and setting up shop there,” said one of the paper co-authors, Dr. Irina Matei, assistant professor of immunology research in pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Moreover, NGFR increases the secretion of the protein intracellular adhesion molecule 1, which encourages tumor cells to bind to lymph vessels, also promoting metastases, Dr. Lyden said.

Building on previous work from this team, Dr. Peinado also investigated how the presence of proteins called integrins on the surface of exosomes determines where metastatic melanoma cells will spread. In this paper, researchers found that integrin alpha is important for spread to the lymph nodes versus other organs such as the liver.

Overall, while the lymph nodes should be sites of immune system activation and tumor rejection, the processes outlined in the study demonstrate that the cancer-fighting function of lymph nodes is compromised by melanoma-derived exosomes, which may have implications for prognosis, Dr. Lyden said.

When someone has melanoma, doctors examine the sentinel lymph node, or the first node to which the tumor will likely spread, to see if it contains cancerous cells. “However, the examination of the sentinel lymph node for just tumor cells is not complete,” Dr. Lyden said. Additional information such as the presence of NGFR or lymphangiogenesis could indicate a poor prognosis for patients, meaning they likely need aggressive treatment.

The research could also have implications for drug development. In a mouse model, Dr. Peinado used a small molecule inhibitor called THX-B to block NGFR from promoting lymphangiogenesis, helping to deter lymph node metastases. “This drug needs a lot of testing,” Dr. Lyden said. “But eventually, I think an NGFR inhibitor could be used in the clinical setting.”

The researchers followed up on the mouse model findings by studying lymph node tissue from 44 patients with stage III or IV melanoma and found that NGFR expression was significantly higher in metastatic lymph node tissues than in the original skin lesions. Evaluation of another 25 patients with stage III melanoma found a significant increase in the frequency of NGFR positive tumor cells in lymph node metastases compared with the originating melanoma tumor.

“Those patients with metastatic disease actually have very high NGFR expression,” Dr. Lyden said. “So, at all stages, whether it's pre-metastatic or full-blown lymph node metastasis, it seems that NGFR correlates with worse prognosis.”

The researchers aim to validate their findings in larger numbers of patients. “We also would like to determine if we can use a simple blood test to see whether exosomes are carrying NGFR,” Dr. Lyden said. “This would help doctors to look at exosomal NGFR over time during therapy to see how treatments should be adjusted.”