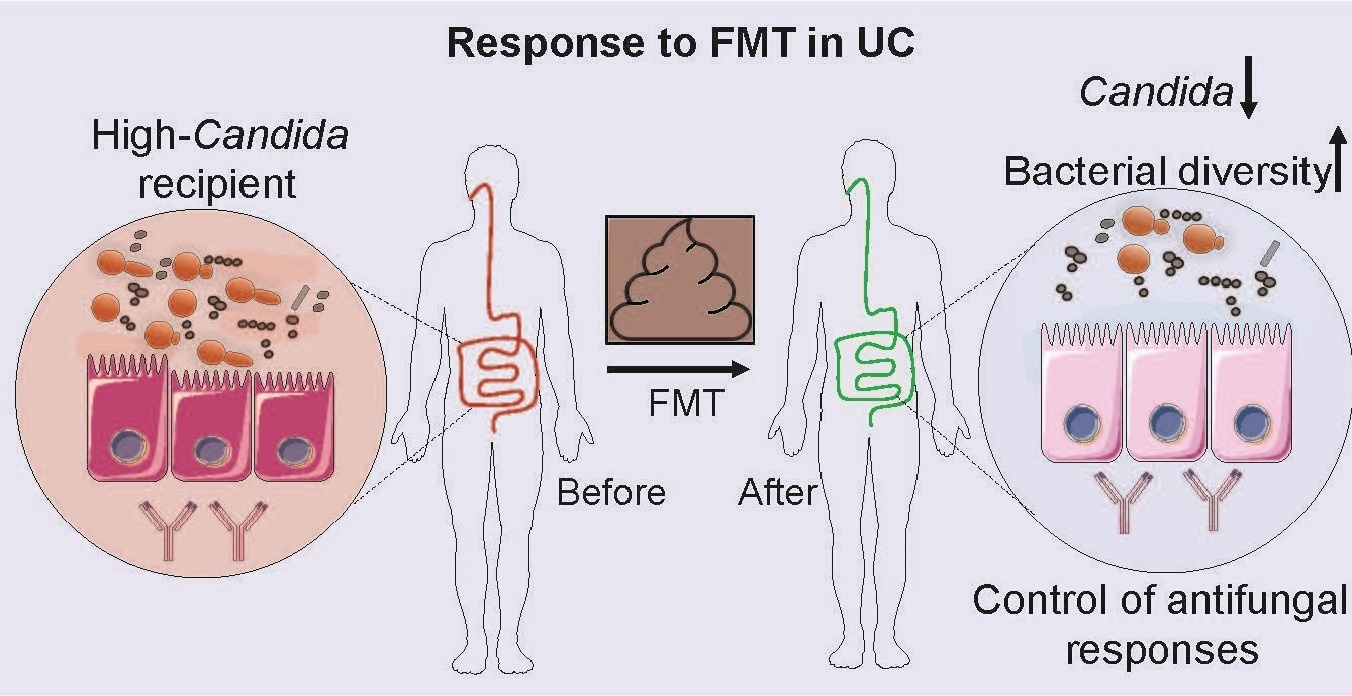

Graphic depicting association of Candida levels with response to fecal microbiota transplant in ulcerative colitis patients.

Higher levels of a type of fungus in the gut are associated with better outcomes for patients with a type of inflammatory bowel disease called ulcerative colitis who are treated with gut microbes from healthy donors, according to a new study by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators.

The study, published April 15 in Cell Host & Microbe, suggests a way to determine which patients may be good candidates for the therapy, called fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), in which stool—and the healthy bacteria, fungi and other microbes it contains—are transferred from a donor to the patient.

Ulcerative colitis is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that causes chronic sores and inflammation in the colon and rectum. Prior research has shown that FMT can promote healing in the mucosal lining of the lower digestive tract, relieving ulcerative colitis symptoms in some people. Based on the new study, those patients who benefit from this therapy have higher levels of the fungus Candida in their gut prior to the procedure.

Dr. Iliyan D. Iliev

“The fecal transplant then acts to decrease the population of Candida,” said senior study author Dr. Iliyan D. Iliev, assistant professor of immunology in medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and co-director of the Microbiome Core Lab at the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine. While more research is needed, the decline in Candida after FMT may help to reduce inflammation in the colon and rectum. “Altered fungus levels may also affect bacteria in the gut, altogether reducing inflammation,” said Dr. Irina Leonardi, first author of the study and a postdoctoral associate in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

About 750,000 people in North America have ulcerative colitis. The disease does not always respond to medication, and while surgery can relieve symptoms, it is not curative. The current research may one day help doctors determine which patients might be candidates for FMT or other microbiome-based therapies.

“If you start giving this treatment to a broad population, your chances of success are lower,” said Dr. Iliev. “In general, what you really need is a target population that has a chance to respond.” The procedure is invasive, requiring the placement of donor feces into the lower digestive tract, typically using a colonoscope, and also carries risks. In 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning after FMT used to treat two patients with life-threatening Clostridioides difficile bacterial infection of the colon caused subsequent E. coli infection, highlighting the need for thorough screening of donor material.

Dr. Irina Leonardi

To better understand how fungi might play a role in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with FMT, Dr. Iliev and his colleagues evaluated stool samples from a large, multicenter, randomized trial of FMT for ulcerative colitis in which patients received an initial colonoscopic infusion followed by multiple administrations of fecal enema from pooled donor material. The investigators analyzed 129 fecal samples from healthy donors and from ulcerative colitis patients prior to FMT or placebo treatment and then eight weeks after the procedures. The researchers also obtained serum samples from patients to study their antibody response to microbes.

Front cover of Cell Host & Microbe's latest issue highlighting the study

Patients who had higher levels of Candida in their gut before receiving FMT responded to the treatment. FMT then acted to decrease the population of Candida. Patients who did not respond to FMT had lower levels of Candida in the gut before the procedure, and after they received FMT, levels of Candida did not greatly change.

The researchers found that people who did not respond to the transplant had increased serum levels of antibodies to Candida. This indicated that the body was unsuccessfully trying to mount immune response to the fungus, which in these patients might prove detrimental: an elevated immune response is part of what causes inflammation in ulcerative colitis.

“This is a very exciting research finding from the Iliev lab and could offer improved precision medicine approaches to FMT for IBD patients in the years to come,” said Dr. David Artis, the director of the Jill Roberts Institute, director of the Friedman Center for Nutrition and Inflammation and Michael Kors Professor of Immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine. “We are delighted the Roberts Institute and Weill Cornell Medicine Microbiome Core was able to support this study and look forward to the next steps.”

Dr. Iliev and Dr. Leonardi want to perform further studies in the laboratory to determine what underlying biological processes explain these study findings. The laboratory also aims to better understand the genetic and immune makeup of ulcerative colitis patients who might respond to fecal transplant. “We hope that upon validation in multiple patient cohorts, findings from this type of studies might one day help doctors decide who should receive FMT or other microbiome-based therapy,” Dr. Iliev said.

The laboratory currently studies how specific fungi and bacteria might interact in the gut to influence the overall microbiota in patients with ulcerative colitis and other diseases that arise from inflammation. “Fecal transplant studies are in their infancy in this respect,” he said.

Research in the Iliev laboratory is supported by the US National Institutes of Health ( DK113136, DK121977 and AI137157 ), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Senior Research Award, the Helmsley Charitable Trust , the Irma T. Hirschl Career Scientist Award, pilot funding from the Center for Advanced Digestive Care (CADC), and the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in IBD. Irina Leonardi is supported by fellowships from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation.