“This was the moment everything changed,” Dr. Matt McCarthy writes of his decision to collaborate on a clinical trial for a promising new antibiotic, “when I went from a passive observer of drug resistance to an active participant in the race to stop the expanding threat of superbugs.” In his latest book, Dr. McCarthy—an assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and an internist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center—chronicles his efforts to conduct the trial, as well as to treat hospitalized patients who have potentially life-threatening infections. Published in May by an imprint of Penguin Random House, "Superbugs: The Race to Stop an Epidemic" is aimed at a general audience. “It’s for anyone who has ever seen a doctor and wondered how they make decisions,” Dr. McCarthy says, “who is interested in the future of medicine and drug development or who just wonders what life is like inside the halls of a major hospital.”

The book includes a historical tour of infection research and treatment, from the battlefields of World War I to the halls of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. McCarthy contemplates ethical issues in drug testing over the past century, describes the systems that have been put in place to protect patients—such as the institutional review boards that oversee research involving human subjects—and offers an impassioned warning about the escalating threat of superbugs that are rapidly outstripping medicine’s ability to combat them. “I spend most of my waking hours thinking about this issue,” Dr. McCarthy admits, noting that “things that were easily treatable with an oral antibiotic a few years ago are now requiring an intravenous antibiotic and hospitalization.”

An image of "Superbugs," book written by Dr. Matt McCarthy

"Superbugs" is Dr. McCarthy’s third book; he has also published "The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly," a memoir of his intern year. In addition to his nearly 50 peer-reviewed articles in academic journals, he has written for such mainstream publications as Sports Illustrated, The Atlantic and Slate, and regularly contributes book reviews to USA Today. “For me, writing is a tremendous outlet that helps me stave off burn-out,” Dr. McCarthy says. “It’s a way to cope with the stresses of the job. It helps me get through the really tough days.”

In addition to chronicling the effects of drug-resistant microbes on patients in "Superbugs," Dr. McCarthy describes the rigorous Institutional Review Board (IRB) review process that he and his mentor and collaborator—infectious disease expert Dr. Thomas Walsh, a professor of medicine in microbiology and immunology and in pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and an internist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center—underwent before conducting their 2017–18 clinical trial. The study assessed the efficacy of dalbavancin, an antibiotic developed by the pharmaceutical company Allergan that is aimed at treating infections resistant to other drugs. (Dr. McCarthy can’t yet comment on the outcome, other than to say that he and Dr. Walsh were “delighted by the results,” which they’ll present at a major conference this summer.)

The dalbavancin study was the first clinical trial Dr. McCarthy had ever led. He found one aspect of the process particularly affecting: the task of recruiting participants. “I suddenly found myself at the bedside of vulnerable patients, asking something of them that they had not anticipated when they walked into the hospital,” he recalls. “I took that responsibility very seriously. Some people would ask me, ‘Would you give this drug to your own mother?’—and that’s a very powerful question.”

Unsung Heroines

In an Excerpt from “Superbugs,” Dr. McCarthy Recalls Two Forgotten Pioneers of Drug Discovery

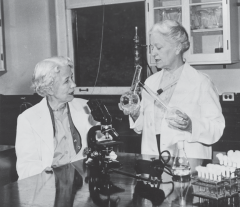

Fungal Detectives: Drs. Elizabeth Hazen and Rachel Brown in the lab

Alexander Fleming’s chance discovery of the first antibiotic is enough to spark the imagination of any child with a budding interest in science, but the discovery of the first antifungal drug is equally compelling. It’s a story about two brilliant women that has been omitted from most science books, and it’s unknown to most of today’s young physicians.

Dr. Elizabeth Hazen was orphaned when she was just three. She spent the majority of her childhood bouncing around rural Mississippi at the turn of the 20th century, living first with her grandmother and then with her uncle. After high school, she attended what is now known as the Mississippi University for Women and then moved to New York to study bacteriology at Columbia University. Her studies were interrupted by World War I, during which she served in the army, but she eventually obtained a doctorate before moving to New York City’s Division of Laboratories and Research in 1931.

A dozen years later, during World War II, physicians noticed that penicillin was protecting soldiers from bacterial infections, but many were contracting fungal diseases. There was no cure, and some suspected that Fleming’s discovery was actually predisposing the men to the fatal infections. Dr. Elizabeth Hazen was tasked with finding a way to treat them. In her laboratory, she went about the painstaking project of isolating organisms found in soil samples and testing them against two fungi that were known to infect humans, Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. When Dr. Hazen had a potential hit, she mailed her samples in a mason jar to a chemist in Albany, New York, named Rachel Brown.

Upstate, Dr. Brown would purify the samples and send the drugs back to Dr. Hazen for testing in animals. Their work progressed at a blistering pace, and was made possible by the remarkable efficiency of the U.S. Postal Service. In just a few years, they reviewed thousands of molecules, but almost all the drugs that killed fungi in test tubes turned out to be highly toxic in animals. Finally, after years of searching, one worked. The compound destroyed fungi without harming animals or humans, and, of all places, it had been found in the garden of Dr. Hazen’s friend, Jessie Nourse. A bacterium in the soil was producing the antifungal drug; Dr. Hazen named it after her friend, Streptomyces noursei.

The two researchers announced their results at the New York meeting of the National Academy of Sciences in 1950 and immediately attracted interest from big pharma, which was entering its golden age. Drs. Hazen and Brown were suddenly rich and, briefly, famous. They invested their millions in a nonprofit that funded more research. They named their fungal drug nystatin, after the New York State Department of Health, and continued to collaborate throughout their lives, discovering two more antibiotics together.

Nystatin has saved countless lives—I prescribe it all the time—and it’s even used occasionally to restore damaged artwork. (After a flood in Florence, Italy, curators at Boboli Gardens sprayed nystatin on more than 200 paintings to protect them from mold.) Its effect has been staggering: it is on the World Health Organization (WHO)’s list of essential medicines and is one of the cheapest and most effective products on the market today. But the nystatin story isn’t taught to fledgling scientists, medical students or residents. Forgetting this piece of history speaks to our failure as educators. Everyone knows about Alexander Fleming, but no one knows about Drs. Elizabeth Hazen and Rachel Brown.

Reprinted from "Superbugs: The Race to Stop an Epidemic" by arrangement with Avery, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © 2019, Dr. Matt McCarthy.

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Spring 2019