Production of an essential protein for maintaining a healthy immune response in the intestine called interleukin-2 (IL-2) depends on immune cells known as innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), according to a study by Weill Cornell Medicine researchers. The study, published April 3 in Nature, is the first to identify these cells and the factors that influence them as potential new targets for treating chronic gut inflammation associated with inflammatory bowel disease or food allergies.

“We have understood for quite a while that IL-2 is important for maintaining a healthy immune response in the gut,” said senior author Dr. Gregory Sonnenberg, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology in medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and a member of the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Dramatic inflammation occurs when humans or mice are missing IL-2, but the specific cells that make it and the regulatory pathways controlling its production in the intestine were previously unknown.”

From left: Dr. Robbyn Sockolow, Dr. Gregory Sonnenberg and Dr. Lei Zhou. Credit: Jennifer Conrad

In a healthy gastrointestinal tract, there is an ecosystem consisting of “friendly” gut bacteria called microbiota that communicate and work together with the body’s immune cells to maintain a balance and protect the gut lining from infection or chronic inflammation. In food allergy or inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, this ecosystem becomes imbalanced and the immune system over-responds, causing excessive inflammation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, reduced appetite and weight loss.

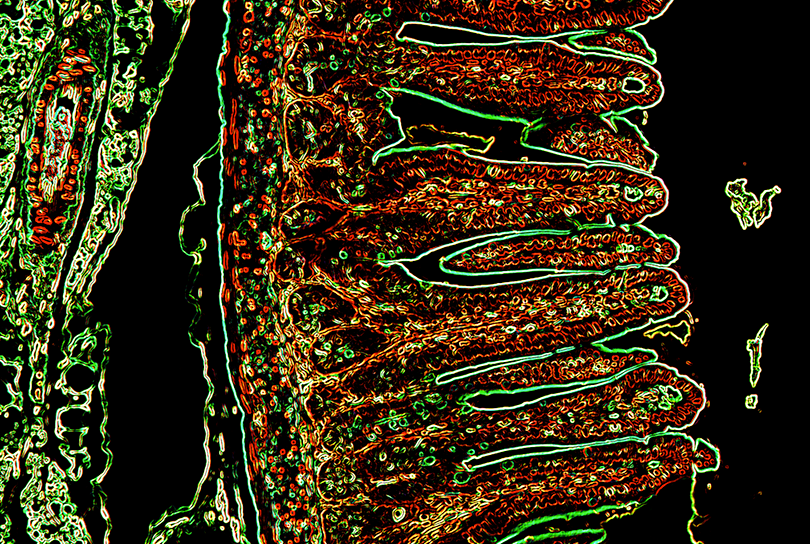

To determine where and how IL-2 – which was originally discovered by study co-author Dr. Kendall Smith of Weill Cornell Medicine– is made, the researchers performed a number of analyses on the gastrointestinal tract of healthy mice. “We found that the production of IL-2 was required to maintain tissue health in the small intestine, but surprisingly the critical cellular source of IL-2 was not what previous studies would predict,” said lead author Dr. Lei Zhou, a postdoctoral associate working in Dr. Sonnenberg’s lab. “Through a number of cellular and molecular approaches, we determined that IL-2 in the healthy small intestine is dominantly produced by a particular type of innate immune cells, called ILCs.”

Next, the scientists performed further studies in mice to identify the signals that prompt ILCs to make IL-2. They discovered that intestinal microbiota send selective messages to white blood cells called macrophages and stimulate them to produce interleukin-1 (IL-1), which in turn triggers the ILCs to produce IL-2. The IL-2 then supports a unique population of T cells that suppress excessive immune responses in the intestine, called regulatory T cells or Tregs. “Our key finding that ILCs are an important source of IL-2 fills in an important missing piece of the puzzle," Dr. Sonnenberg said. “It explains how the intestinal microbiota interacts with the immune system to maintain Tregs and homeostasis in the gastrointestinal tract.”

Finally, the researchers studied human small intestine tissue samples provided by pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and compared them with children without the disease. “We were able to conduct these studies with support of patients and their families, as well as a unique partnership between the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in IBD and the Pediatric IBD Program,” said study co-author Dr. Robbyn Sockolow, a professor of clinical pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and director of gastroenterology and nutrition at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital. “We found that patients with Crohn’s disease had significantly lower numbers of IL-2 producing ILCs in their small intestines, indicating that this pathway is clinically important and paving the way for future translational research.”

Dr. Sonnenberg and his team plan to investigate specific microbes that could potentially boost IL-2 production in people with Crohn’s disease or food allergies or who have depleted gut microbiomes as a side effect of cancer treatment. “In the future,” Dr. Sonnenberg said, “it may be possible to develop cocktails of microbes to stimulate the production of IL-2 from ILCs and restore tolerance in the gastrointestinal tract of patients with these chronic diseases.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI143842, R01AI123368, R01AI145989, R21DK110262 and U01AI095608), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mucosal Immunology Studies Team, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the Searle Scholars Program, the America Asthma Foundation Scholar Award, Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, a Wade F.B. Thompson/Cancer Research Investigator CLIP Investigator grant, Cure for IBD, and the Rosanne H. Silbermann Foundation.