A previously unknown type of T lymphocyte, a class of white blood cell, contributes to the development of an autoimmune disease, called lupus, which causes the immune system to attack healthy tissues and organs and leads to chronic inflammation, according to a study led by Weill Cornell Medicine researchers.

The study, published Nov. 26 in Nature Medicine, suggests that targeting this newly discovered class of T cell, or its biochemical signals, may be a good strategy for treating lupus. Current treatments do not cure the disease and often cause broad immune suppression that increases the risk of infection and cancer.

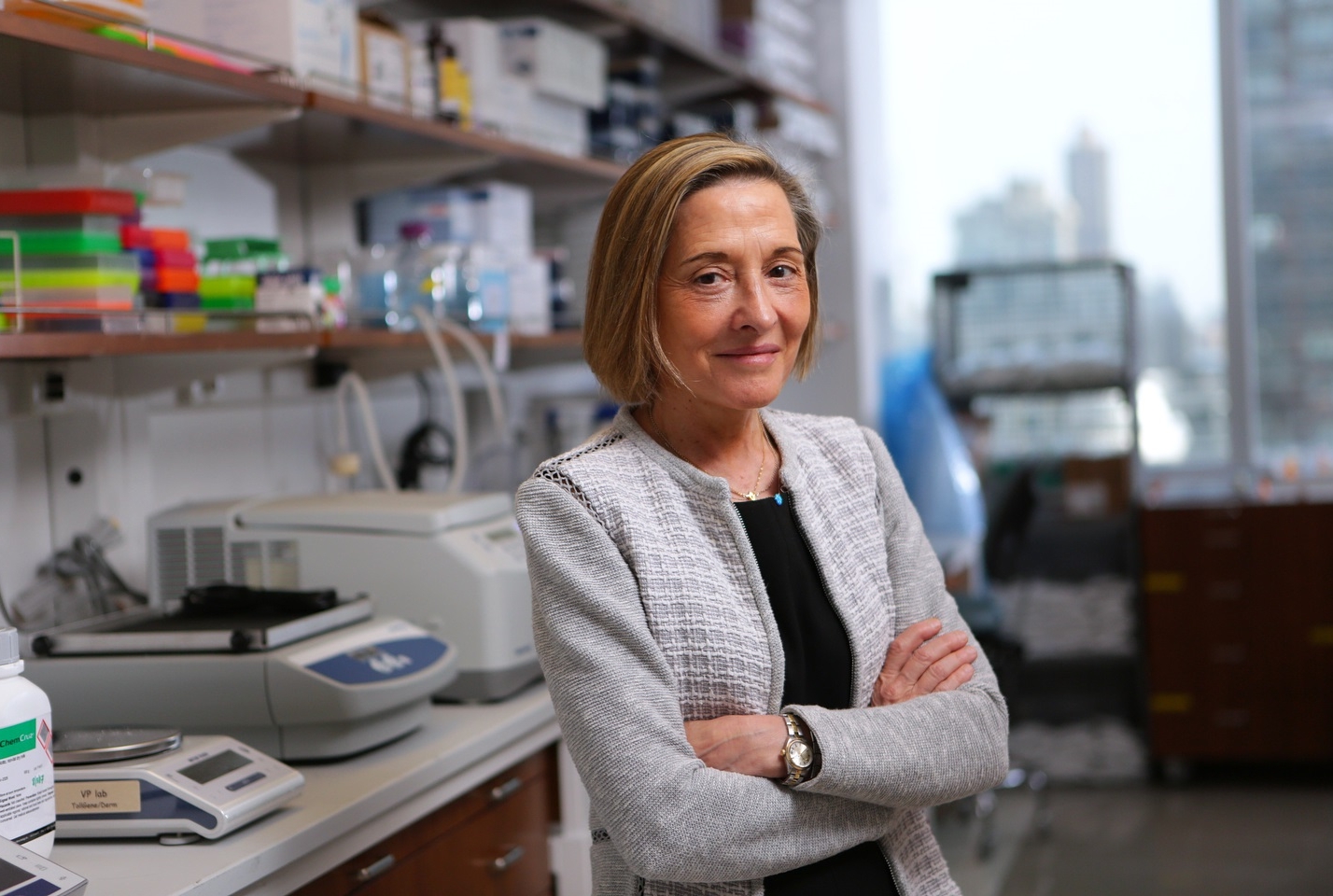

“We’re very interested in exploring the possibility of developing new treatments based on this finding,” said senior study author Dr. Virginia Pascual, the Drukier Director of the Gale and Ira Drukier Institute for Children’s Health and the Ronay Menschel Professor of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The most common form of lupus, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is thought to afflict roughly 150,000 to 300,000 people in the United States. It is more prevalent among women and people of African, Hispanic, Asian or American Indian descent, and while it is often considered an adult disease, it occurs relatively frequently in children—for whom it tends to take a more severe course. The disease generally involves attacks on the body’s own tissues by antibodies and other immune elements, with symptoms ranging from skin rashes and fatigue to seizures and severe heart and kidney problems.

Investigators still do not know how lupus arises and why antibodies that react with DNA are so prevalent in this disease. Much of the research has focused on a class of T cells called T follicular helper cells, which are produced at higher levels in lupus patients and help activate many of the immune cells, called B cells, that go on to produce tissue-attacking antibodies. Dr. Pascual and colleagues also have shown in prior studies that these lupus “autoantibodies,” when they encounter immune cells called neutrophils, can cause the neutrophils to release damaged DNA. This appears to set up a vicious cycle of intensifying immune activity, as other immune cells called dendritic cells react to the damaged DNA as if it were from viruses.

For the new study, the scientists looked more closely at what these dendritic cells do when they encounter this type of damaged neutrophil DNA, taken in this case from lupus patients. The key finding was that the dendritic cells somehow activate T cells in the vicinity to become “helper” T cells, of a previously unseen type that the scientists propose calling TH10 cells. These helper T cells go on to stimulate antibody-making B cells, and they do so by producing a unique combination of signaling molecules: the immune protein IL-10, and a small molecule called succinate, which is better known as a byproduct of cellular energy production.

“This is a B-cell activation pathway that has never been described before,” said Dr. Pascual, who has received a research grant and consulting honorarium from Sanofi-Pasteur.

The scientists found relatively high levels of the new type of helper T cell in lupus patients’ blood and also in the kidneys of those affected by a serious lupus-related kidney disorder called proliferative lupus nephritis. Receptors for succinate are particularly common on kidney cells and there is evidence that their overstimulation contributes to other, non-lupus forms of kidney disease. Dr. Pascual and her colleagues therefore suspect that while the newly discovered helper T cells may harm lupus patients’ kidneys by increasing the production of lupus autoantibodies, they may also cause direct harm to the kidney by producing succinate.

The scientists are now examining the possibility of blocking succinate signaling or some other element of this new B-cell activation pathway to ameliorate lupus nephritis and other aspects of this autoimmune disease. “Our study opens up a range of potential targets for treating lupus,” Dr. Pascual said.