When longtime research collaborators Dr. Douglas Nixon and Dr. Brad Jones arrived at Weill Cornell Medicine last summer, they brought with them an ambitious goal: to find a cure for HIV. The two, who came to Weill Cornell Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases from The George Washington University, have decades of combined experience in studying the ways in which HIV survives by evading the human immune system. Thanks to a five-year, $28 million grant from the NIH, the two researchers—along with more than a dozen colleagues in the United States, Canada, Mexico and Brazil—are working together to find ways to harness the body’s own defenses to eradicate HIV; Dr. Nixon is principal investigator of the project, dubbed BELIEVE (for Bench-to-Bed Enhanced Lymphocyte Infusions to Engineer Viral Eradication). Dr. Nixon, a Brit who was recruited as a professor of immunology in medicine, and Dr. Jones, a Canadian who was recruited as an assistant professor of immunology in medicine, each runs his own lab at Weill Cornell Medicine, conducting both joint and individual research projects. In July, Dr. Jones gave the basic sciences plenary lecture at the 2018 International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam.

What drew you to HIV as a research focus?

DR. NIXON: I was a medical student in London in the early 1980s, a time at which a mysterious new disease was affecting young gay men in Los Angeles and New York. I was given an epidemiological project to investigate the limited literature of this new problem, and it piqued my interest. Then, early in my internship at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, I went into the room of a 19-year-old man who had fever and symptomatology of what we would later know to be acute HIV infection. I was 22 or 23, and I could imagine the fear and issues that were facing him, and I felt that this was something I really wanted to work on. As it happened, six weeks before I was due to start my PhD program in immunology at the University of Oxford, two seminal papers came out in the journal Nature describing cell-mediated immunity to HIV.

DR. JONES: For me there was never any doubt that I would end up working with HIV. It was something I was really passionate about. As a gay man, I was quite scared of HIV. Even though it wasn’t the bad old days of the 1980s—there was treatment—it was something I was very conscious of, and my way of confronting that was through basic science research. In addition to being frightened of the virus, I was fascinated by how it found a way to get around some of the antiretroviral drugs we used to try to stop it. HIV was interesting as an adversary.

What makes HIV such a formidable opponent?

DR. NIXON: When HIV was first discovered, it was thought that a vaccine might be developed easily. But it wasn’t—and that identifies one of the big problems we have with HIV, which is that it mutates and changes. It’s like the ultimate in clothes shopping; it likes to go out and get a new coat every day. To make a vaccine, we tend to need one static “coat” that we can immunize against. But the virus has a very clever mechanism that it uses to hide from constant immune attacks, almost like a weapon that can bury into a bunker and stay there until it’s woken up.

DR. JONES: In some ways, it’s the virus’s sloppiness that gives it its great strength. Because it’s mutating in so many ways at once, even though most of them are dead ends it’s going to find a path to escape the things we throw at it—although we do think there are ways to outsmart it.

Given that drug regimens have made HIV a manageable disease, why is it still important to find a cure?

DR. JONES: One reason is that drug therapy is not a perfect solution. It’s expensive, it’s a lifelong commitment and health disparities persist; even people who are successfully treated develop more co-morbidities related to cardiovascular disease, renal disease and malignancies than those who are not. The second reason is that HIV still has lessons to teach us. When we pursue different biomedical approaches to cure HIV infection, we learn lessons that can be translated to other conditions; for example, the understanding that a molecule called PD-1 suppresses T-cells in humans came from HIV research, and that is now a pathway that’s targeted in cancer and is saving lives. The third is that on an aspirational level, this is a disease that has caused so much loss and grief over the years. Isn’t a cure the ultimate victory over this epidemic?

DR. NIXON: In many countries around the world, there is still a real stigma of HIV infection; if we can cure people, that would be partially resolved. And as Brad mentioned, even in people who receive drug therapy and have the virus suppressed for a long period of time, there still appears to be a mortality gap. The other thing is that more people continue to be infected. During the course of the conversation we’re having right now, unfortunately thousands more people will acquire the virus around the world. To stop that, we either need a vaccine, we need a cure, or we need to treat enough people so the virus is undetectable and they can’t transmit it to others—or some combination of the above.

Why did you choose to bring your research to Weill Cornell Medicine?

DR. NIXON: There were a few big reasons. First, I knew of the work of Dr. Roy “Trip” Gulick, who is chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and has a very strong clinical program in HIV research. Overall, Brad and I were trying to find a location that has strengths in basic, translational and clinical science, and where our work would have relevance for local populations. At Weill Cornell Medicine there are outstanding scientists who are working in different areas, but have the potential to really contribute to HIV research—though they may not know it yet. (He laughs.) And as Brad said, HIV is a master educator; it knows more about the immune system than we do. HIV has helped drive the study of immunology in a way that is still permeating into gastroenterology, neurology, neuroscience and a number of other areas that are very strong at Weill Cornell Medicine. The Tri-Institutional element of collaborating with outstanding people at The Rockefeller University and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center was also a draw.

DR. JONES: During our interviews at Weill Cornell Medicine—and since we arrived—we encountered people who are brilliant and inspiring, but also friendly and welcoming. I think it has a “best of both worlds” balance, where people are successful and driven, but also open to working together. And Trip is an inspiring figure—he had one of the most prominent roles in the first triple-drug therapy for HIV, which led to the success of medications as we know it.

How do you complement each other as research partners?

DR. JONES: Doug brings a depth of experience, but also a fresh enthusiasm for new ideas. I’ve learned a lot from him about science and how the field works in practice.

DR. NIXON: We’ve worked together for some time, and we’ve found that we’re both really curiosity-driven. That makes it easy to work with someone, because they don’t automatically discount crazy ideas.

Could you give an overview of your work with BELIEVE?

DR. NIXON: We have a spectrum of ongoing research, from the test tube to clinic. We have not yet conducted our first clinical trial, but we’re hopeful that next year we will do so.

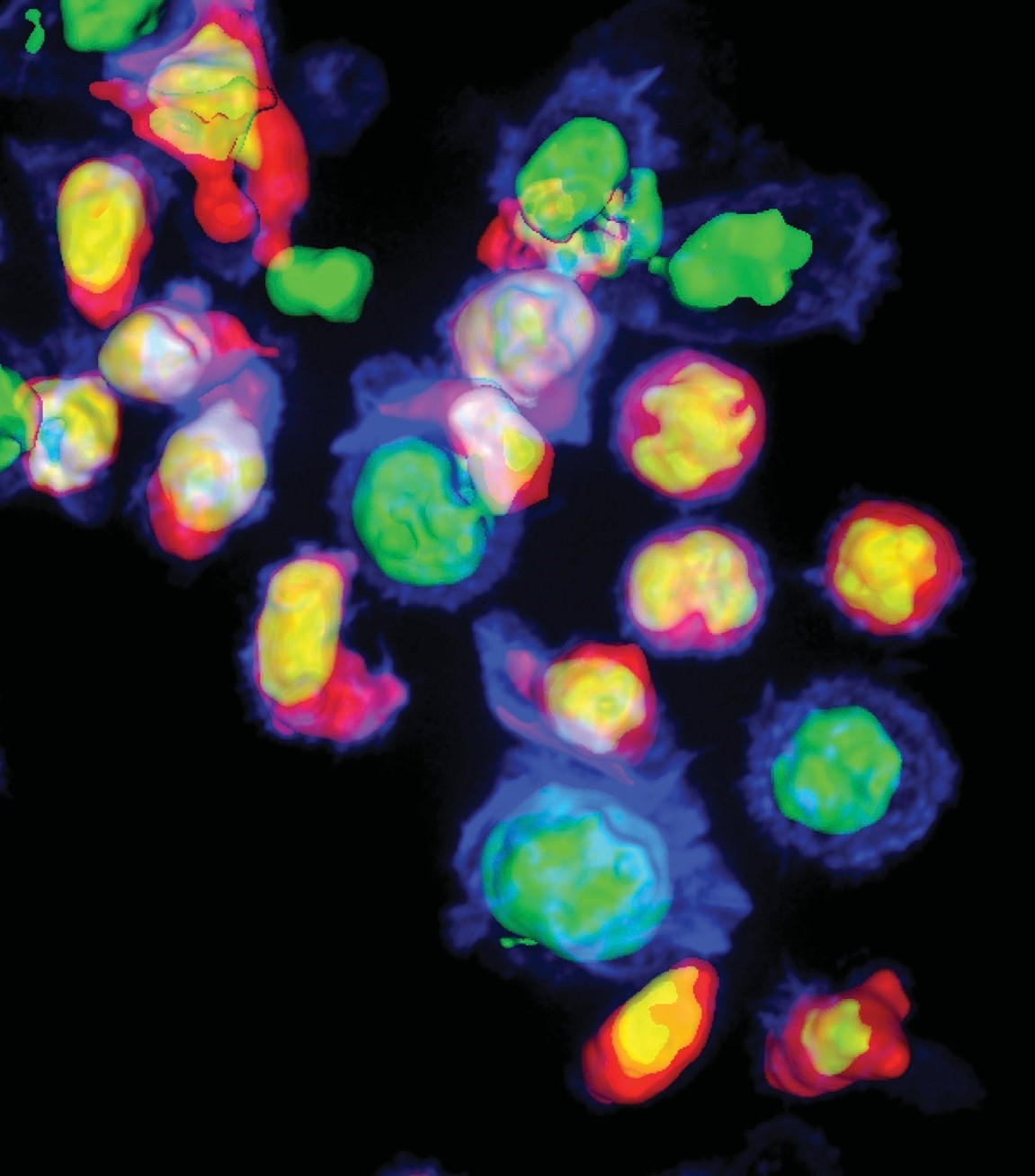

DR. JONES: A lot of our efforts are based around harnessing the immune system. We think it actually does a pretty good job against HIV; the T-cell response is probably one of the major reasons it can take six, seven, eight years to progress to AIDS instead of just a few weeks. What we want to do is enhance that. Maybe it’s not going to take much to tip the balance to where the immune system can control HIV for life, or eradicate the reservoir. In T-cell therapy, we take the person’s own cells and manipulate them in vitro to try to redirect them against parts of the virus that we think are more vulnerable, or can’t escape as easily. We think that’s going to be a powerful approach.

On the Offensive: So-called “killer” T-cells (seen in pink and yellow) attacking cells that are infected with HIV (seen in blue and green). Photo: Sudha Kumari

What do you find most gratifying about working in this field?

DR. NIXON: I have been studying this virus for 30 years, and it has been an educational path for me. When I started, we didn’t know what this virus was—we were at the beginning of a new disease for which there was no treatment. Then combination therapy came; now, we have a program to see if we could potentially cure this. It’s a microcosm of time in which you progress. There have been positive benefits for people, but you also realize that many people did not have that benefit.

DR. JONES: For me, it’s the chance to interact and be inspired by people living with HIV. Our work is all based on using samples from them, often collected through a procedure in which people have a needle put into each arm and are hooked up to a machine for about two hours. We have people who have done this 10-plus times. They’re healthy; they’re not doing it because they need different treatment, they’re doing it for altruistic reasons. To me, this is a remarkable cross-section of the general population—people who, even though they often come from marginalized communities, show this unusual generosity.

— Beth Saulnier

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Fall 2018