An existing malaria drug could improve the effectiveness of a new class of cancer therapies, called glutaminase inhibitors, if used in combination, researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar (WCM-Q) discovered in a new study.

The research, published May 17 in Cancer Letters, analyzed the metabolic processes of cancer cells to show that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved, quinine-based malaria drug Chloroquine could boost the effectiveness of the new glutaminase inhibiting drugs, which are currently being developed by global pharmaceutical companies. The findings could offer doctors and researchers a relatively simple way to improve outcomes for cancer patients who are prescribed glutaminase inhibitors.

Glutaminase inhibitors target a chemical process called glutaminolysis, in which the amino acid glutamine is broken down, releasing energy that cancer cells use to grow. Glutaminase inhibitors seek to disrupt this process, thereby depriving cancer cells of their energy source and slowing or stopping their growth. However, certain cancer cells can activate alternative ways to generate energy and thereby escape the drug’s action. This is where a new research approach called “rational metabolic engineering” comes in.

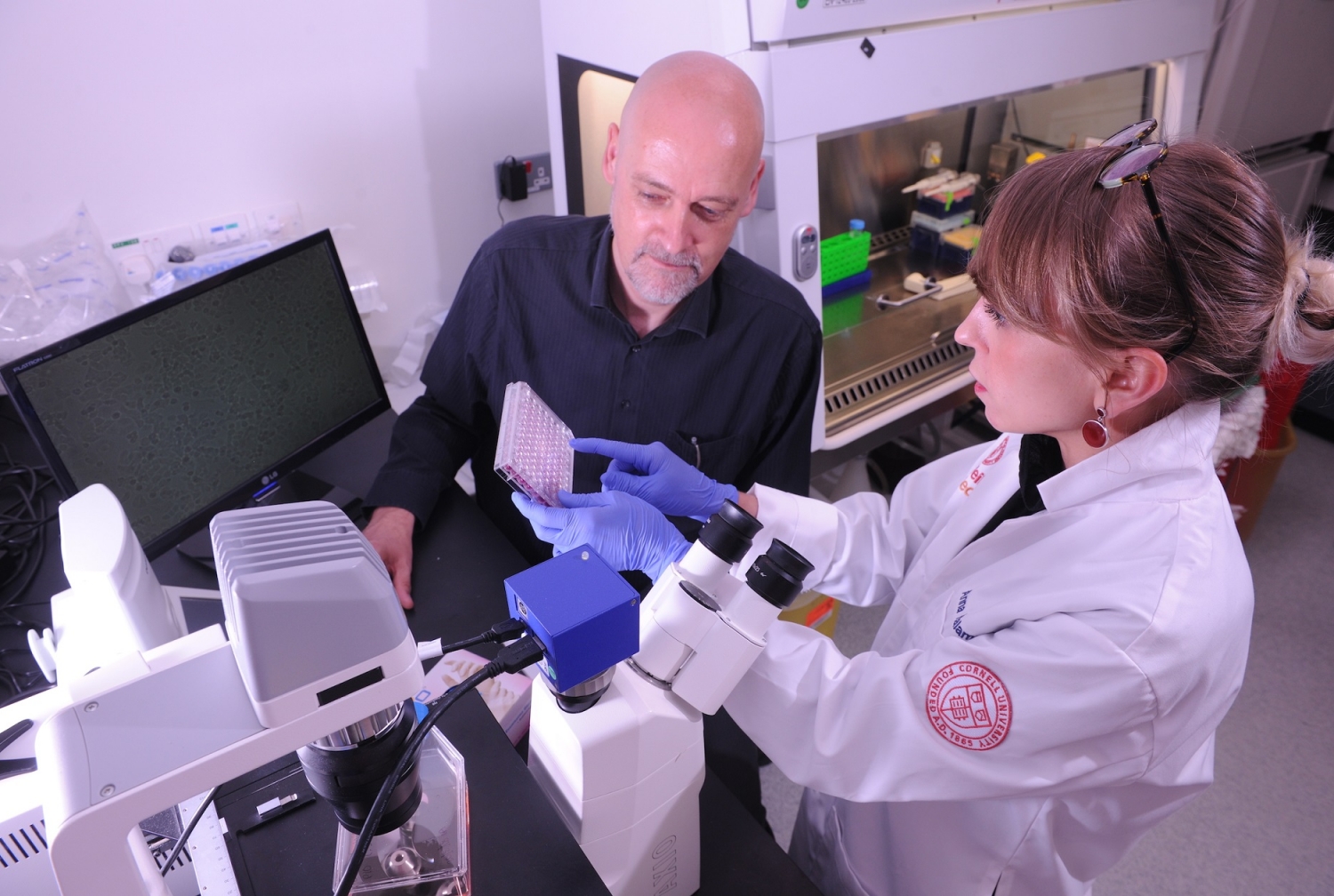

“We expose cancer cells grown in the laboratory to different doses of an anti-cancer drug and then measure the changes in almost all of the small molecules that are present in the cells, using a technique called metabolomics,” said lead author Dr. Anna Halama, a research associate in physiology and biophysics. “Using sophisticated computational methods, we then identify the molecules that the cancer cells are using to escape the drug’s actions, and conceive ways to block that escape route.”

In this first application of approach to glutaminase inhibitors, the researchers focused on two specific energy pathways that cancer cells use: lipid catabolism, which is the breakdown of fats, and autophagy, in which cells derive energy by degrading parts of their own structure. They found that both of these energy pathways were accelerated when the glutaminolysis pathway was suppressed with drugs, which allowed the cancer cells to survive.

“Since the anti-malaria drug Chloroquine is known to disrupt some of these energy-producing mechanisms,” Dr. Halama said, “our research prompted us to theorize that giving Chloroquine in combination with the glutaminase inhibiting drugs could lead to an improved suppression of tumor cells, which turned out to be the case.”

“The beauty of metabolomics profiling is that it lets us see how the cell’s metabolism behaves in different situations and with a very high level of detail,” said senior author Dr. Karsten Suhre, a professor of physiology and biophysics and director of the bioinformatics core at WCM-Q. “So with this method we can get very useful insights into the effects a drug has on the metabolism of tumor cells, helping us to understand how the disease works and to identify targets for potential new treatments.”

The findings may provide physician-scientists with a new strategy that can be replicated in other therapies. “The combined approach used in this study is uniquely relevant for future therapeutic strategies in cancer treatment and can be easily generalized to other drugs. The next important step is to test the efficacy of Chloroquine in combination with glutaminolysis inhibitors in a clinical trial.”

Dr. Khaled Machaca, associate dean for research at WCM-Q, said: “This type of research combining deep -omics phenotyping under specific pathological conditions identifies novel therapeutic interventions, in this case applied to cancer, that could be powerful in terms of disease interventions. The funding provided by QNRF for this type of research goes a long way toward both improving our basic knowledge base and generating potential therapeutic tools for Qatar and the world.”

The study was fully supported by Qatar National Research Fund (QNRF) grant NPRP8-061-3-011.