Patients who receive red blood cell (RBC) transfusions before, during or immediately after surgery are twice as likely to develop life-threatening, postoperative blood clots as those who don’t undergo RBC transfusions, according to a new study by Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian researchers.

The investigators say their findings, published June 13 in JAMA Surgery, underscore the need for physicians to consider non-transfusion alternatives to treat anemia in patients undergoing surgery, to minimize red blood cell transfusions and their possible deleterious effects.

“These findings reinforce the importance of following rigorous perioperative patient blood management practices for transfusions,” said first author Dr. Ruchika Goel, an assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and assistant professor of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine, and assistant medical director of transfusion medicine and cellular therapies at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Every drop of blood we are transfusing should be used only if necessary and it needs to be an evidence-based decision.”

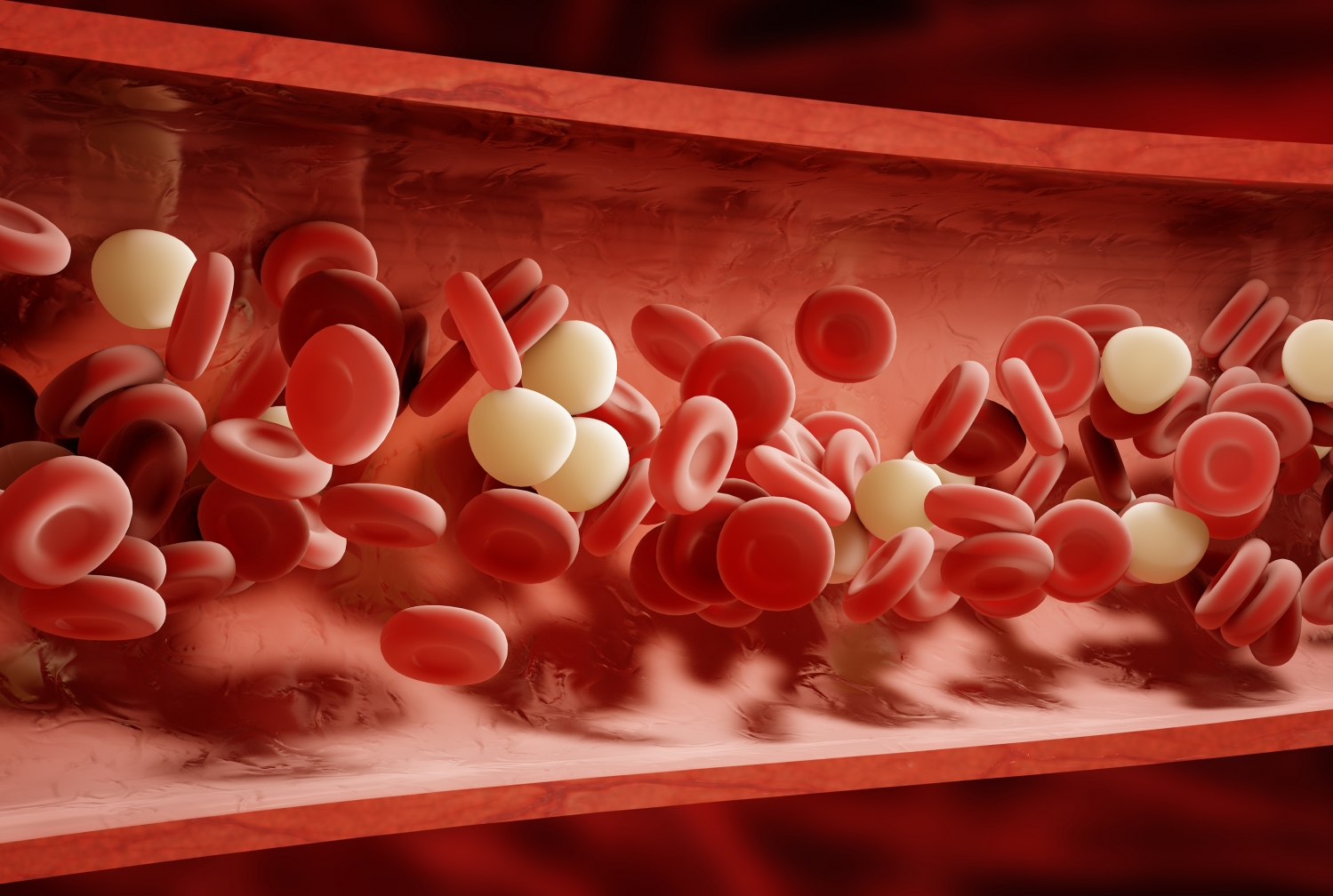

Red blood cells contain the protein hemoglobin, which carries oxygen to the body’s organs and tissues. Doctors commonly prescribe RBC transfusions during the surgical process because operations can cause blood loss, which, in turn, can lead to low oxygen levels in the body and increase the risk of organ damage.

Up to 200,000 people die each year in United States directly and indirectly from blood clots that develop in the veins, also known as venous thromboembolism (VTE). Clots that occur deep within the veins—most often in the legs—are called deep venous thrombosis (DVT). They can break loose and cause life-threatening blockages in the lungs called pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Surgery is a known risk factor for blood clots,” Dr. Goel said. “Because patients can be in a state of immobilization after surgery, blood clots tend to form. They can also occur in the post-operative state once patients return home and are slowly regaining their activity levels.”

Traditionally, researchers have considered RBCs to be passive bystanders to the clotting process, Dr. Goel said. However, some recent findings indicate that RBCs may have an active role. While multiple approaches studying the relationship are being explored, the exact mechanistic pathways on how they contribute to clotting is not yet understood.

To understand that connection, Dr. Goel and her colleagues, including senior author Dr. Aaron Tobian, professor of pathology, medicine and epidemiology, and director of transfusion medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, strategically analyzed a database compiled by the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. The study evaluated 750,937 patients who underwent surgery in 2014. Of these patients, 47,410, or 6.3 percent, received at least one RBC transfusion. Of the 750,937 patients, VTE occurred in 6,309 (0.8 percent) of them within 30 days of surgery. Deep vein thrombosis developed in 4,336 (0.6 percent) patients, 2,514 (0.3 percent) had pulmonary embolism and 541 (0.1 percent) encountered both.

After conducting a risk analysis, the researchers found that patients who received RBC transfusions were twice as likely to develop clots than those who did not undergo the procedure. This was true for VTE, DVT and PE.

“We also saw this risk across different surgical disciplines, ranging from neurosurgery to cardiac surgery,” Dr. Tobian said. Moreover, when the researchers analyzed data adjusting for other risk factors, RBC transfusions still increased the odds of a blood clot by two-fold.

In addition, the researchers found that the risk of a blood clot increased with the number of RBC transfusions a patient received. Those who underwent two transfusions had a 3-fold risk of a blood clot, while those who underwent three or more transfusions had a 4.5-fold risk.

“This retrospective study demonstrates that there may be additional risks to blood transfusion that are not generally recognized in the community,” Dr. Tobian said. “While, additional research is need to confirm these results. The findings reinforce the need to limit blood transfusions to only when necessary.”

Fortunately, there are alternatives to red blood cell transfusion, Dr. Goel said. To increase hemoglobin levels, doctors can give iron or the drug erythropoietin, which encourages red blood cell formation. Ideally, these options should be used two to four weeks before surgery, making them a practical option for patients who are undergoing elective surgery, she said.

Patients who need to undergo more urgent surgical procedures should receive anti-clotting medications such as heparin before or after their operation to prevent clotting, and be closely monitored for blood clots, Dr. Goel said.

Overall, the rate of RBC transfusions is declining, Dr. Goel said, referring to a paper published Feb. 27 in JAMA that she led as the primary author.

“It is very encouraging that we have nationwide evidence supporting the overall decreasing use of blood products and the adherence to evidence-based transfusion practices,” she said. “Doctors are learning that less is more. If they order a transfusion, they can use the bare minimum that is necessary.”