At what is thought to be the world’s oldest HIV/AIDS clinic, based in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, clinicians recently interviewed some longtime patients with the disease—one that’s all too common in the Caribbean nation, which has the highest infection rate in the Western Hemisphere. Among the survivors was a mother who spoke proudly of living to see her daughter attend university. Another rejoiced at being able to celebrate her grandchild’s First Holy Communion. And yet another shared plans to take a pharmacology class, with the dream of opening a drugstore one day.

Years ago, all that would have been nearly impossible for most Haitians with AIDS. Back when these patients were first diagnosed, HIV-fighting drugs weren’t available in the impoverished country, so doctors expected many to die within 12 months. But in early 2003, the Haitian Study Group on Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections—a nonprofit known as GHESKIO (its French acronym) that provides AIDS care and other services throughout the country in partnership with Haiti’s Ministry of Health and the Weill Cornell Medicine Center for Global Health—obtained funding from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to start a free treatment program for those with the illness. Over the next year, more than 1,000 adults began antiretroviral therapy, a combination of drugs that suppresses the virus and reduces the risk of transmission—and they were among the first to receive such lifesaving medication in a developing nation.

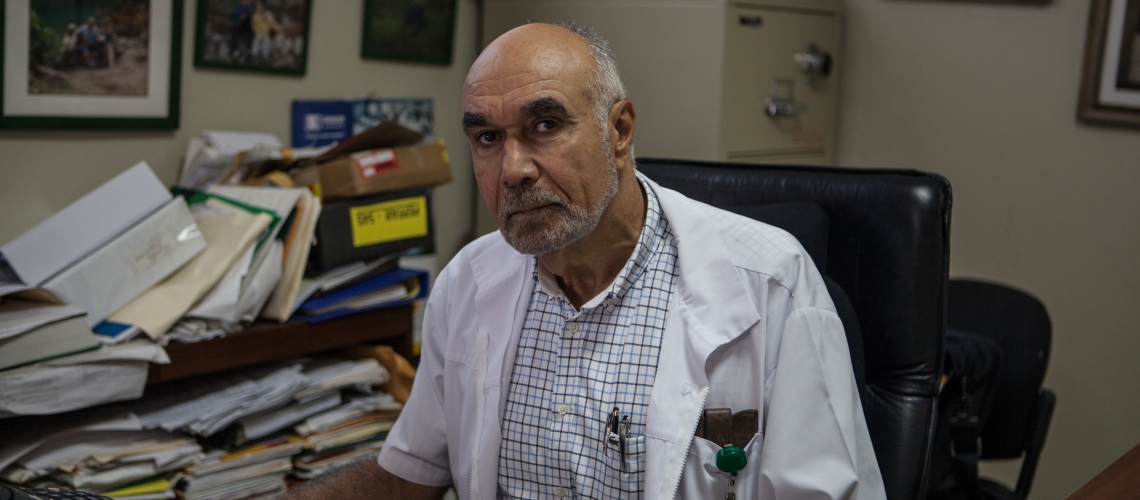

The program has proved highly successful: in a study published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators at GHESKIO and Weill Cornell Medicine reported that more than two-thirds of the initial 1,000 patients enrolled were still alive a decade later, about the same survival rate as their counterparts in the United States. “It’s had a Lazarus effect,” says co-author Dr. Jean Pape (MD ’75), the Holtzmann Professor of Clinical Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, who has directed GHESKIO since its founding in 1982. “These people have gone from certain death to actually leading a fairly normal life.”

More than half of the patients in the program already had full-blown AIDS by the time they started taking antiretrovirals. Among the participants, the median CD4 count—which measures the number of white blood cells that protect the body from infection—was 131. (A CD4 count in an uninfected, healthy person is between 500 and 1,600.) Plus, many were malnourished, suffering from other opportunistic infections like tuberculosis and living on less than $1 a day. “These people were incredibly, incredibly ill,” says senior author Dr. Margaret McNairy, the Bonnie Johnson Sacerdote Clinical Scholar in Women’s Health and an assistant professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine.

Yet Dr. Pape notes that before President George W. Bush announced the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a multi-billion-dollar global health initiative created in 2003 that largely supported GHESKIO’s therapy program, some prominent scientists argued that antiretrovirals should not be given to patients in the developing world. According to Dr. Pape, the concern was that those patients would not follow the complex treatment regimen, leading to drug-resistant strains of the disease entering the United States. “As it turned out,” says Dr. Pape, “that was not true at all.” In fact, compliance was higher than anticipated: five years after treatment began, researchers calculated that the majority of the original 910 patients in Haiti had an adherence level of 90 percent or more. Ten years later, investigators found that about 70 percent of patients had survived—a mortality rate comparable to Americans who started antiretroviral therapy when it began in the 90s. “Sick people desperately want to get better,” says Dr. McNairy, an internist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “If you’re sick, you can’t work and you can’t support your family.”

Although GHESKIO tracked follow-up appointments and assigned field workers to locate people who missed check-ups, participants were responsible for taking their daily medication unsupervised. And unlike AIDS patients in more developed nations, those in Haiti faced astounding obstacles including extreme political unrest, a cholera epidemic and the devastating 2010 earthquake. “It’s like the sky falling on your head,” says Dr. Pape. “When you have all of these odds against you, and you can make it 10 years? It’s really incredible.” That high survival rate has had a ripple effect, too. “It’s amazing to see almost a generation that’s been protected,” says Dr. Daniel Fitzgerald, director of the Center for Global Health and a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases. “It has not only helped the many people who received treatment for HIV, but the many families that were spared the loss of a loved one.”

Challenges Remain

Still, the crisis is far from over. Yes, infection rates have been falling: statistics from the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) show the percentage of HIV-positive Haitian adults has dropped from 6.1 percent in 2001 to less than 2 percent today, thanks to prevention programs, education efforts, and treatment services like GHESKIO’s. But the country still leads Latin America and the Caribbean region with the most overall cases of HIV—in 2015, there were 130,000—and AIDS-related deaths (8,000 in 2015). Among the hardest to reach are 10 to 24-year-olds, particularly girls and young women. According to UNAIDS, adolescents and youth account for 40 percent of new HIV infections every year around the world, with deaths among that group having increased by 50 percent over the last decade. “Adolescents are a highly vulnerable group that has been neglected in the past with little dedicated interventions for them,” says Dr. Vanessa Rouzier, GHESKIO’s head of pediatrics and nutrition. “We now recognize that we urgently need adolescent specific strategies to help these vulnerable youth cope and thrive with this disease, as well as prevent new infections in that group.

Dr. Rouzier oversees Haiti’s largest pediatric AIDS clinic; since joining GHESKIO in 2009, she has noticed a dramatic reduction in the number of babies infected at birth, which she attributes to more support programs for pregnant women and an increased number of HIV-positive mothers on antiretroviral medication. But unfortunately, she says, young people are still at risk—with many contracting the disease later on through sexual contact. “If we want to end the AIDS epidemic, we need to have everyone on board—not only adults but adolescents and children as well,” says Dr. Rouzier. “Different age groups need different strategies.”

One of the difficulties is that young Haitians—most of whom live in extreme poverty and have low levels of education—are more likely to engage in risky behavior, though organizations like GHESKIO are promoting HIV prevention methods including condom use. Another problem is that for those who already have the disease, few realize that they’re infected. In fact, UNICEF estimates that only nine percent of adolescent females and four percent of adolescent males in Haiti who are living with HIV know their status. Among the barriers to getting tested: children and young adults don’t think they’re at risk for contracting the disease, clinic hours often conflict with school, and there’s a stigma associated with visiting an HIV clinic. Dr. Fitzgerald says these challenges aren’t restricted to Haiti, and he believes the lessons learned there can be applied elsewhere. “HIV is slowly becoming a disease of teenagers around the world,” he says. “Learning how to adapt our care for that demographic is going to be critical.”

Dr. McNairy is working with Dr. Rouzier and her colleagues on new ways to increase testing among vulnerable youngsters. For nine months starting in December 2014, GHESKIO ran a community-based campaign in seven impoverished neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince, setting up booths that offered a comprehensive package of healthcare services for 10 to 24-year-olds, including same-day testing for HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy and screening for tuberculosis. This way, HIV/AIDS wasn’t singled out for testing—and the strategy worked. Of 3,425 young people, with a median age of 19, 98 percent agreed to an HIV test. The results, published last year in the journal AIDS Patient Care and STDs, confirmed that these adolescents and young adults were an important high-risk population. “We found a prevalence rate among adolescents and youth that was up to six-fold higher than the national rate,” says Dr. McNairy, who led the project, which was supported by the MACAIDS Foundation and led the way to additional NIH funding.

Teens who tested positive were taken to GHESKIO’s HIV clinic right away for treatment and counseling. But as Dr. Rouzier stresses, “Getting them to come get tested is just the first thing. Getting them to stay in care—and eventually take their medication—is the other challenge.” So she, Dr. McNairy and others set up a pilot program to address that obstacle. Rather than continuing to see each patient individually at the main adolescent clinic, GHESKIO established a branch at a local community center, where groups of five to eight youths would meet every month for check-ups by a nurse and to receive support from their peers. “It decreased the stigma and normalized having the disease,” says Dr. McNairy. “And it created this incredible surrogate family that provided much-needed social support and a sense of belonging.” Preliminary outcomes from the program are promising. Dr. McNairy says that 90 percent of participants were still in care for a year after they tested positive, compared to only half of those youngsters seen at GHESKIO’s main clinic. Her team recently received a $2 million, four-year NIH grant—entitled FANMI, which is Creole for “family”—to further study the effectiveness of a community-based peer group strategy in a randomized clinical trial.

Overall, Dr. Pape says, there are currently more than 80,000 people in Haiti receiving treatment—one-third of them through the GHESKIO network—and he expects more potent new drugs to soon become available. “That will be even more significant in reducing the amount of the virus in the blood,” he says. Dr. McNairy adds that, moving forward, the programs in Haiti can be an especially helpful model for other underdeveloped places around the globe, such as parts of Africa where adult HIV prevalence rates are as high as 30 percent. “This work isn’t a Band-Aid solution to ending the HIV epidemic,” says Dr. McNairy. “We’re making a real difference.”

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Vol. 16. No. 4