Women diagnosed with an infectious parasitic disease prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa are at increased risk of contracting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and both men and women who had this parasitic disease developed higher HIV viral loads after becoming HIV-infected, according to a study from Weill Cornell Medicine investigators.

The research, published Sept. 25 in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, details a 10-year study investigating the interaction of the disease schistosomiasis with HIV among adults in the Lake Victoria region of Tanzania. The investigators found that women who had schistosomiasis were more likely to subsequently become HIV-infected, while men with schistosomiasis were not at increased risk. The factors placing women at risk are not fully understood, said lead author Dr. Jennifer Downs, the Friedman Family Research Scholar in Pediatric Infectious Diseases, an assistant professor of medicine and of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

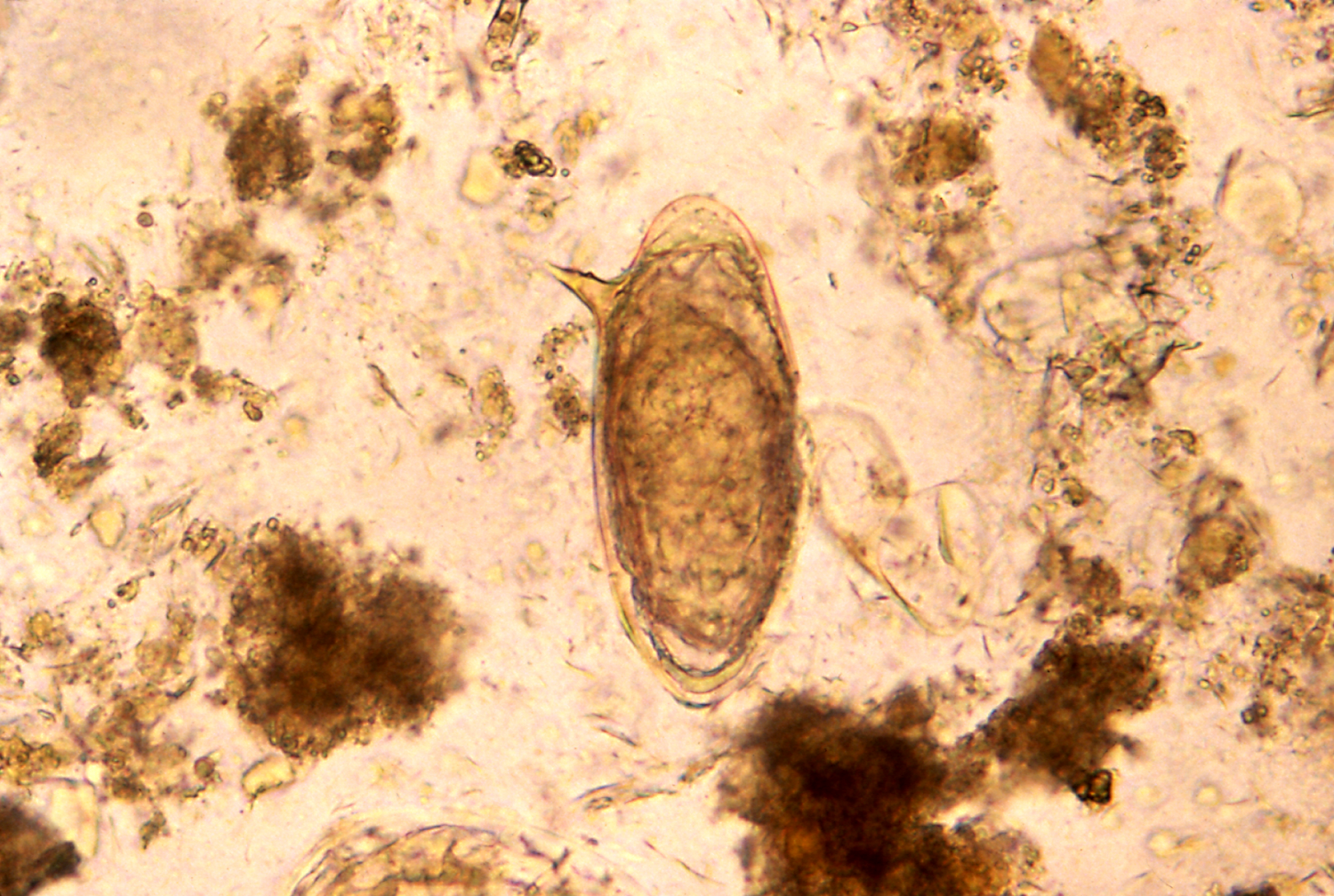

Up to 50 percent of rural Tanzanians, and more than 200 million people worldwide, live with schistosomiasis, a disease that can be contracted when people come in contact with water contaminated with the parasite. These Schistosoma worms penetrate the skin, mature in the human host and then reproduce in the infected host’s blood vessels. The worms lay thousands of eggs each day that migrate through the surrounding tissue into the urogenital and intestinal tracts. If untreated, schistosomiasis can lead to organ damage and even death.

The investigators determined the prevalence of schistosomiasis in blood collected from adults who tested positive for HIV for the first time in 2007, 2010 and 2013. They then compared those samples with blood from adults who repeatedly tested negative for HIV. The project’s success was built on long-term collaborations between investigators from the Weill Bugando School of Medicine and the National Institute of Medical Research in Mwanza, Tanzania, Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands, and Weill Cornell Medicine.

The investigators discovered that women are at greater risk of becoming HIV-infected. This is likely because parasite eggs in the female genital tract affect the cervix and vagina and they cause inflammation and bleeding there, Dr. Downs said. Eggs in the male genital tract cause damage in internal genital organs such as the prostate, which are not exposed to HIV during sexual contact.

The investigators also found that the pre-existing schistosome infection increased the HIV viral load in both men and women early in the course of the HIV infection. Higher HIV viral loads lead to faster progression of HIV disease and death.

Dr. Downs said schistosomiasis treatment in sub-Saharan Africa is primarily targeted to school children. The team’s findings indicate that physicians can put greater emphasis on treating schistosomiasis in adults as a strategy to control HIV infection in endemic areas. “We should be treating the entire community, not only the children,” Dr. Downs said. “I hope this paper will lead to a growing consensus that we need to treat schistosomiasis in everybody, and that it can have major impact for HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa.”