By Beth Saulnier

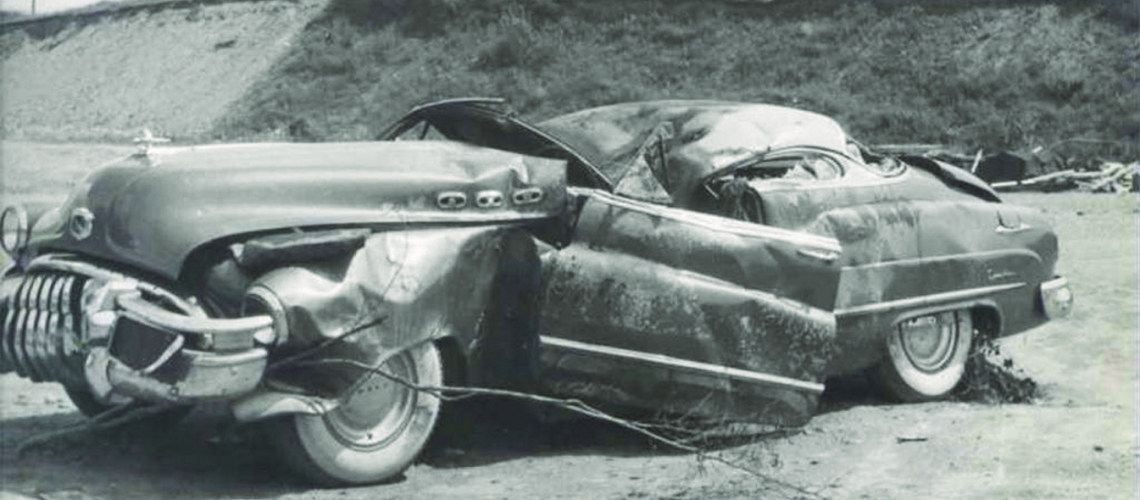

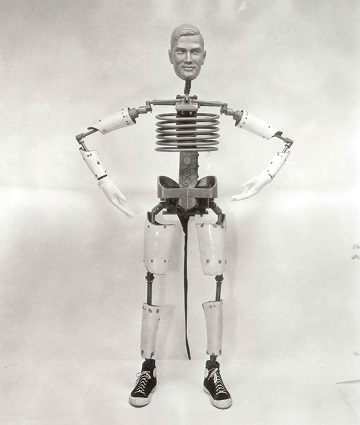

From the collected papers of automotive safety pioneer Hugh De Haven, a photo of an early crash-test dummy.

“We rarely get people who just accidentally show up,” Lisa Mix, Weill Cornell Medicine’s head archivist, says with a chuckle, “because you have to make a real effort to get here.” Located on the 25th floor of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center’s Baker Tower — and accessible only by a human-operated, limited access elevator — the archives are the repository of Weill Cornell Medicine’s history. Supported by NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine, they contain more than 7,100 linear feet of materials — primarily documents but also videos, sound recordings, physical objects and an estimated 20,000 photographs covering the medical college, the medical center and antecedent institutions such as the Bloomingdale Asylum and the Lying-In Hospital. The facility attracts researchers and scholars from both within and outside the institution, and its materials have been used in such projects as a PBS documentary on the 1918 influenza pandemic and Ken Burns’ “Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies.”

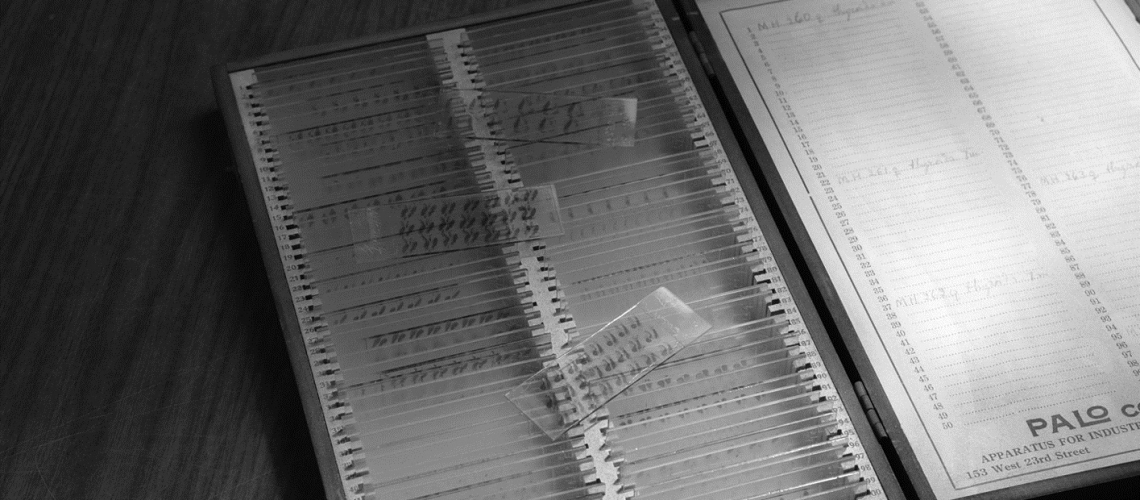

Among the archives’ most intriguing holdings are hospital casebooks containing handwritten patient records dating from 1808 to 1932. They’re the focus of a current project by Dr. Curtis Cole, MD ’94, Weill Cornell Medicine’s chief information officer, who received a $50,000 grant from the Frank Naeymi-Rad and Theresa A. Kepic Foundation to scan the pages for the purposes of research and preservation. Dr. Cole is also overseeing an effort by a computer science master’s student at Cornell Tech to develop methods of machine-learning to transcribe the records into searchable text.

“You learn a lot of medicine by transcribing an old medical record,” Dr. Cole observes. “The ways that doctors view patients and how they conceptualize a case haven’t changed — and even much of the diagnosis is still the same.” Other gems include the archives’ oldest item: the charter from England’s King George III that established New York Hospital in 1771.

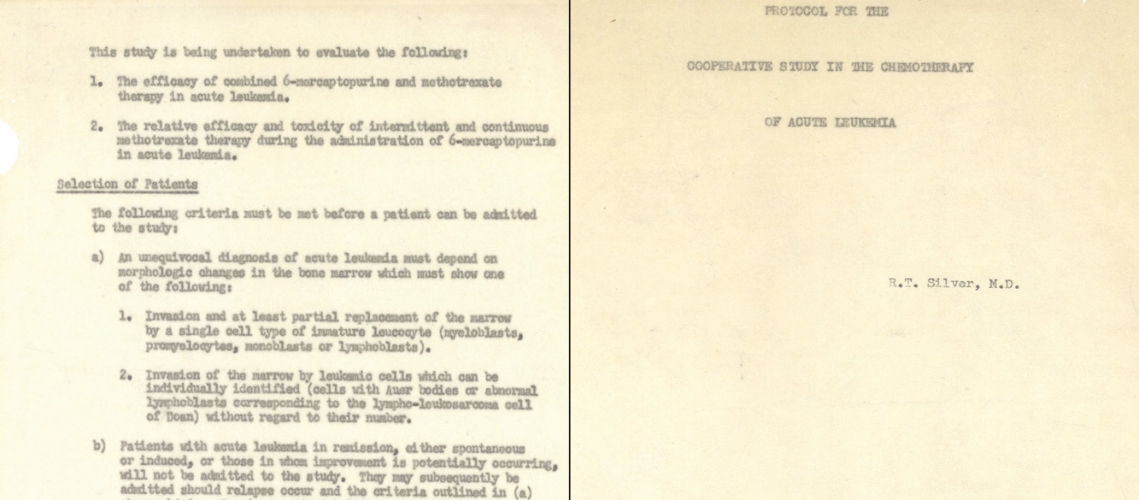

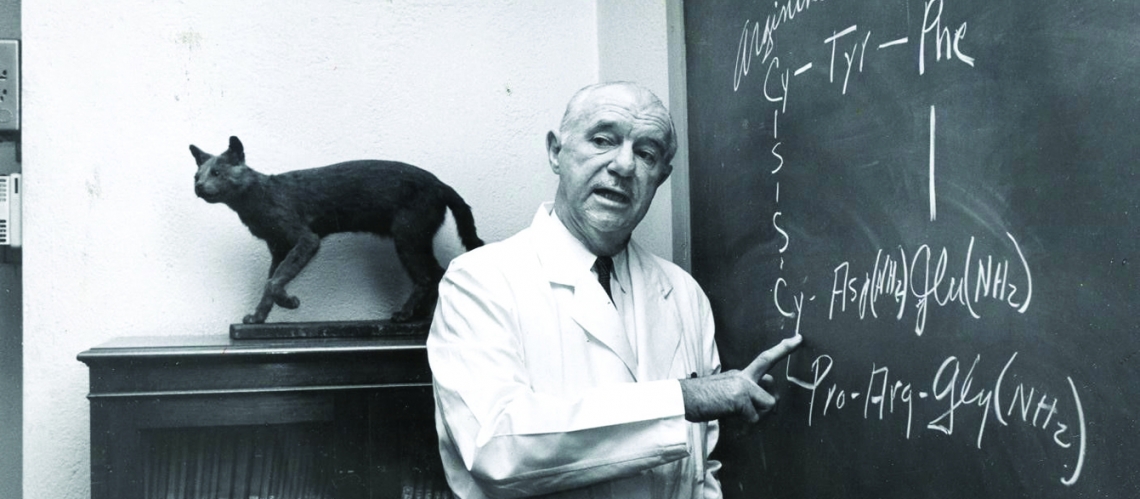

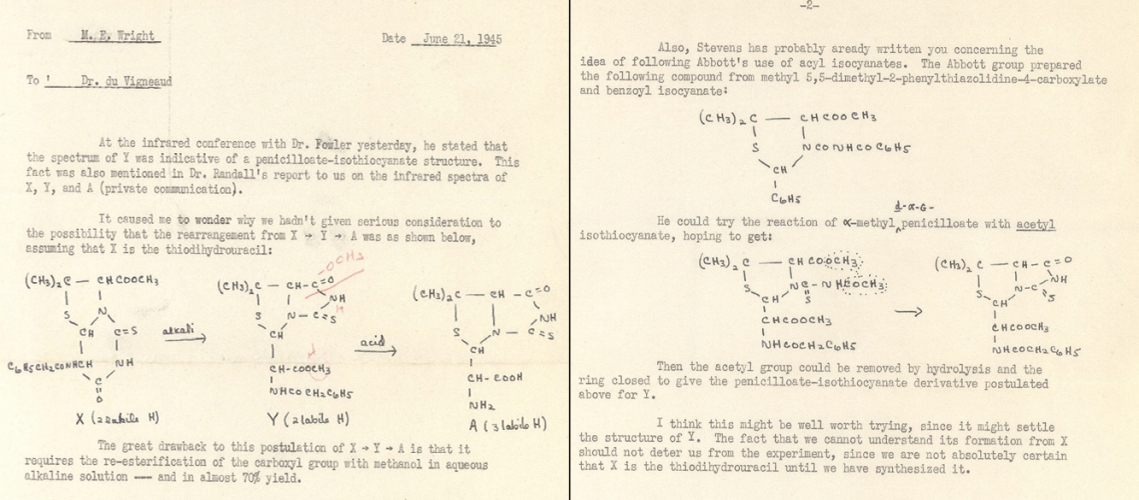

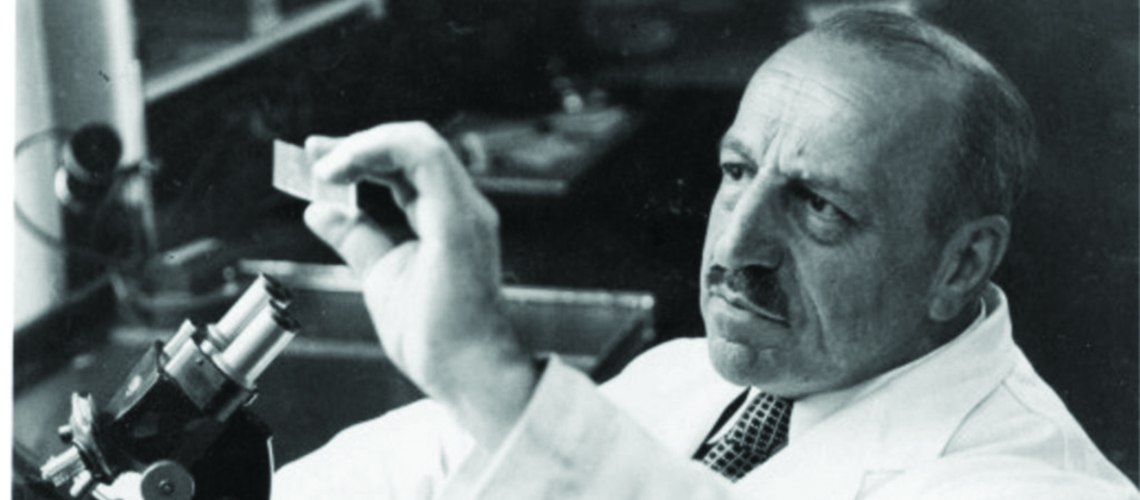

Part of Weill Cornell Medicine’s Samuel J. Wood Library, the archives are also home to the collected papers of numerous Weill Cornell Medicine researchers, chronicling their decades of discovery. The following pages showcase a sampling of those holdings, documenting work in fields from cancer to automotive safety. “The archives are a very special place,” says Dr. Cole. “It really is the crown jewel of the library.”

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Vol. 16. No. 2