Up to 30 percent of HIV patients who are appropriately treated with antiretroviral therapies develop the chronic lung disease emphysema in their lifetime. Now, new research from Weill Cornell Medicine investigators has uncovered a mechanism that might explain why this lung damage occurs.

In the study, published May 9 in Cell Reports, investigators show how the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, binds to stem cells, called basal cells, which transform into other types of cells that line the airways. This process reprograms the basal cells, causing them to release enzymes, known as proteases, which can destroy lung tissue and poke holes in walls of the air sacs, where oxygen is exchanged.

“This research is important because although antiretroviral agents have turned HIV into a chronic, rather than deadly, disease, the viral reservoirs that remain in the lungs and other tissue continue to cause serious side effects,” said senior author Dr. Ronald Crystal, chairman of the Department of Genetic Medicine and the Bruce Webster Professor of Internal Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, and a pulmonologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Now that we have more information about how the HIV virus might cause emphysema, we can learn more about this potential enzyme target and work towards developing a therapy to prevent this lung damage from happening.”

Since antiretroviral agents have been used to treat the 18.2 million people in the world who are HIV positive and have access to these drugs—1.2 million of them in the United States—lifespans have greatly extended. But as HIV positive people have lived longer, they’ve also been diagnosed with degenerative disorders of the brain, heart and lungs at a higher rate than the general population. Many scientists have investigated how long-term HIV treatment leads to these outcomes. Some posit that the antiretroviral drugs themselves might contribute to these issues, while others have investigated the role of inflammatory cells. This study doesn’t discount earlier theories, Dr. Crystal said, but rather reveals a new mechanism by which the virus attaches itself to and reprograms basal airway cells, that should be further investigated as a possible therapeutic target.

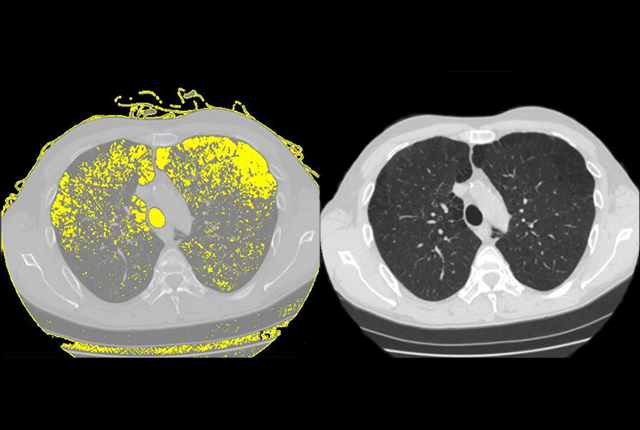

To conduct this research, investigators took normal human airway basal cells, collected from the lungs of healthy nonsmokers, and under observation, exposed them to HIV for a set period of time. Rather than entering and reproducing in the basal cells, the virus instead bonded to the basal cells’ surface and reprogrammed them to start producing an enzyme, or protease, which can break down proteins and destroy tissues, called metalloprotease-9. Because investigators know that emphysema, a disease of the air sacs, starts in the airways, this finding suggests that when basal cells take on what Dr. Crystal called a “destructive phenotype,” they start eating away at healthy tissue, which in time, results in emphysema.

“To see how a virus modifies the function of a cell is an important observation,” Dr. Crystal said, noting that the Zika virus operates in a similar manner by infecting neural stem cells and changing their function, which leads to a birth defect characterized by a smaller than normal head and abnormal brain, called microcephaly.

“Our next step is to conduct additional research to determine what the preventative therapeutic target might be,” Dr. Crystal said, adding that the protease is a likely suspect, “and then, since basal cells are so important to normal lung anatomy and lung function, determine the other side effects of this re-programming.”