By Beth Saulnier

In a senior center in the Bronx’s Riverdale neighborhood, the lunch tables have been pushed aside to make room for an hour-long tai chi class. Most of the participants — an ethnically diverse, predominantly female group of about 30 — are seated in orange plastic chairs, though some are in wheelchairs; at around the midway point, those who are able will stand up for the class’ more dynamic second half. A few walkers are parked at the periphery and a dozen canes line the floor, evidence of their owners’ physical challenges. Still, the students follow their instructor’s movements with energy, gusto and interest. “As you move your hands, try to feel the air,” the teacher tells them as they perform a motion called Repulse Monkey. “Imagine the air being thick. Feel it against the back of your hands, against your palms, between your fingers. The more you can feel the air as you move through it, the more attention you’re paying to the exercise. The more you’re thinking about what’s for supper, the less good the exercise is going to do.”

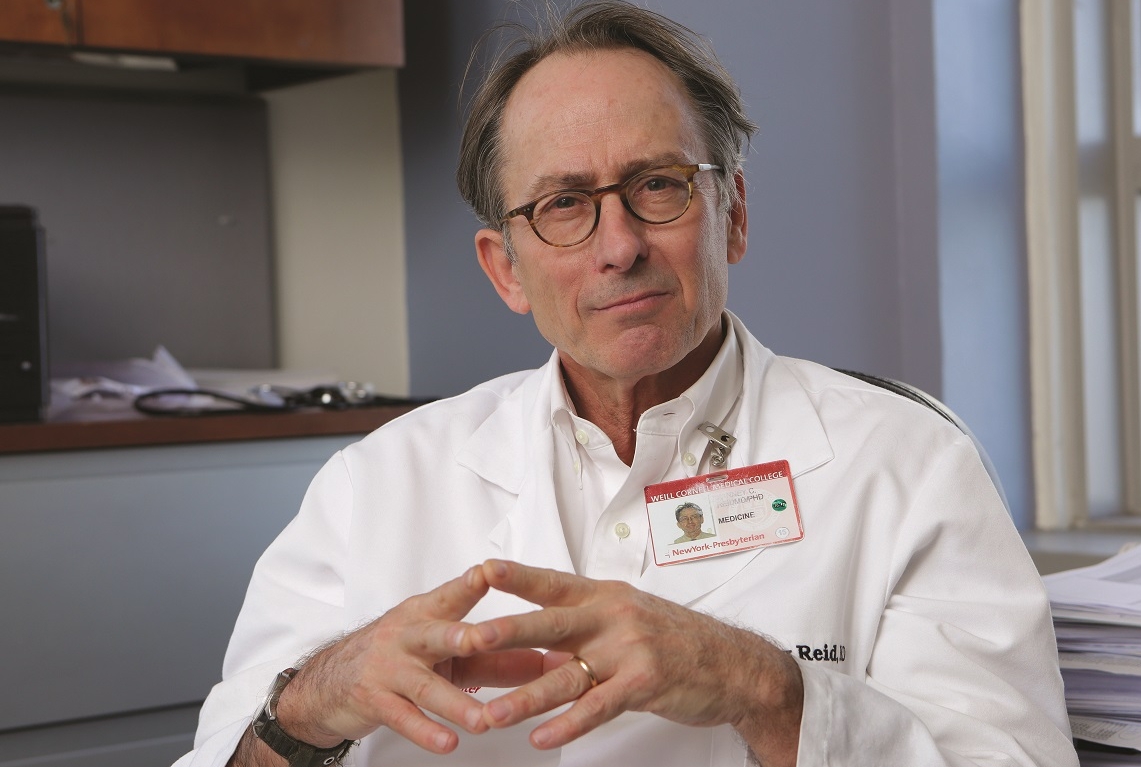

The class, held twice a week at Riverdale Senior Services, is entitled Tai Chi for Balance and Fall Prevention — but its benefits go far beyond what the name implies. It gets older adults out of their apartments and into a social setting. Its movements help make participants stronger and more limber. Its meditative aspects can lower stress and improve mood. And to top it all off, it helps combat one of the greatest ills that many older adults face: chronic pain. “We often use this haiku bullet: ‘Pain is common, morbid and costly,’” says pain expert Dr. Cary Reid, an associate professor of medicine and the Irving Sherwood Wright Associate Professor in Geriatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine. “It’s one of the most common reasons that bring people to the doctor, and we spend a lot of money — not all of it very effectively — trying to manage it.”

BODY AND MIND: The twice-weekly tai chi class at Riverdale Senior Services in the Bronx routinely draws dozens of participants. Photo by John Abbott

Activities like the tai chi class trace their roots to a collaborative project between Riverdale Senior Services and a research group that Dr. Reid directs, a Cornell University-based organization dedicated to exploring ways to alleviate pain in older adults. Called the Translational Research Institute on Pain in Later Life (TRIPLL), it’s one of the most active and long-standing collaborations among the Cornell campuses — comprising researchers and graduate students in Ithaca, at Weill Cornell Medicine and at Cornell Tech, plus dozens of community organizations serving seniors in New York City. “It’s a very broad and deep collaboration,” says co-director Dr. Karl Pillemer, a professor of human development on the Ithaca campus who holds an appointment as a professor of gerontology in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Because of our use of video conferencing, Skype and frequent meetings, it’s honestly not much different than if we were all in the same building. A number of us work with our TRIPLL colleagues even more than with people on our own campuses.”

Dr. Karl Pillemer. Photo by Chris Kitchen/CMG

Founded in 2009 with a five-year grant from the NIH’s National Institute on Aging (which was renewed in 2014), TRIPLL is one of 12 federally funded Edward R. Roybal Centers for Translational Research on Aging nationwide, each of which focuses on a different aspect related to the health and well-being of older Americans. With a concentration on non-pharmacologic methods of pain relief, TRIPLL brings together faculty from a variety of disciplines, including clinical medicine, epidemiology, gerontology, the social and behavioral sciences, computer science, and more. “Pain is a huge problem — it’s one of the things that keeps people homebound,” says Riverdale Senior Services director Julia Schwartz-Leeper, who regularly consults with Dr. Reid and uses the institute’s webinars to train her staff. “The work that TRIPLL does is critically important.”

A Growing Problem

Given America’s aging demographics, the issue of treating pain in older adults is only getting more pressing. TRIPLL co-director Dr. Elaine Wethington, a medical sociologist who’s a professor of human development on the Ithaca campus, notes that one-third of older adults has chronic pain — “and the majority of those find inadequate relief.” Dr. Wethington goes on to point out that rising obesity rates will only make the problem more dire. “Pain is more prevalent among people who are overweight or obese,” she says, “and Baby Boomers are more likely to be overweight and obese than the generation before.”

Dr. Elaine Wethington. Photo by Jason Koski/Cornell Marketing Group

Effective, evidence-based alternatives to pharmaceuticals are sorely needed, TRIPLL researchers say. One reason is that older adults may have pre-existing conditions, such as heart failure or kidney problems, that analgesics frequently exacerbate; they are also often on multiple medications with which pain drugs interact. Older adults with cognitive issues may have trouble adhering to a dosage regimen. “Being80 with pain is different than being 40 or 12, because of the other conditions that people often have as a consequence of getting to 80,” Dr. Reid says. “So these co-morbidities begin to constrain treatment choice.”

The epidemic of opioid abuse also complicates matters. Fear of addiction, even if unfounded, may discourage older people from taking pain drugs, or may make their adult children wary. And, Dr. Pillemer points out, reducing the number of opioid prescriptions can have larger benefits — by, say, keeping the drugs out of a medicine cabinet where they could be misused by family members or others. “Our inability to deal with chronic pain through non-drug methods is a huge problem,” says Dr. Pillemer, who adds that research on eldercare issues has shown that watching a loved one suffer untreated pain takes a marked toll on caregivers. “In terms of an issue that makes the largest number of people miserable, chronic pain is at the top. But it’s not a high-profile problem that has an easy cure, so it doesn’t attract as much research funding.”

With the aim of countering that, TRIPLL awards grants for pilot studies; holds monthly ‘work in progress’ seminars linking researchers on the various campuses; mentors grad students, post-docs, fellows and junior faculty; and serves as a resource to New York City community service agencies, whose tens of thousands of clients provide a deep bench of volunteers for research studies. “For years there’s been a consensus among researchers that pain is not just a biological phenomenon, it’s also a social and a psychological one, but there are few centers in the United States that look at pain from this biopsychosocial perspective,” says Dr. Wethington, who also holds an appointment as a professor of gerontology in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Our commitment is to understand these aspects as completely as we can — to get really smart people working on them, to publish papers in places where they’ll have an effect on practice.”

Community Focused

Dr. George Kaufman has treated pain as a physician — and experienced it as a patient. Now 85, the Riverdale internist retired in 2000; around that time he developed severe pain in his neck, which was traced to spinal stenosis. “I went through all kinds of stuff including three epidurals, which did nothing,” says Dr. Kaufman, chatting at Riverdale Senior Services on a Wednesday in November. “I was on a series of drugs including oxycontin and fentanyl, which didn’t do a lot for me. I wound up mostly using acetaminophen and codeine, six to eight pills a day.” Eventually, Dr. Kaufman adopted a daily regimen of mindfulness meditation, which has allowed him to reduce his use of drugs. “I start breathing into the area of my neck, trying to soften that area, to relax it,” he explains. “As I breathe out I focus on letting the toxins in my neck go out. I keep doing that and get into a meditative state. It really does help — not all the time and not perfectly, but I’m down to four codeines a day.”

Given Dr. Kaufman’s personal and professional interests, he was an eager participant when researchers from TRIPLL — then in its earlier incarnation, the Cornell Institute for Translational Research on Aging — came to the senior center in 2008 seeking participants for a study. Called Taking Community Action Against Pain, it evaluated the efficacy of an Arthritis Foundation pain control program, which included strategies and exercises for stretching, endurance and relaxation. Dr. Reid, Dr. Pillemer and other colleagues were studying the program’s efficacy at three senior centers with different client bases: the Riverdale one, whose members are largely white and Jewish; one in Harlem that predominantly serves African Americans; and another in the Bronx with a heavily Latino and Latina client base.

STAYING ACTIVE: Research participant and retired internist Dr. George Kaufman at Riverdale Senior Services. Photo by John Abbott

The study, which found that the program had clear benefits across all ethnicities, helped forge strong partnerships between the researchers and the agencies — and even the participants themselves. Dr. Kaufman, for one, was inspired to found a pain support group that he ran for several years. “The TRIPLL people have been tremendously helpful,” says Andria Cassidy, deputy director of Riverdale Senior Services. “They were the impetus for us addressing pain management, period. We as a community resource need to integrate pain management into everything we do. Even having lunch with friends and socializing — that can be a distraction from your pain.”

The TRIPLL researchers stress that their relationships with community partners are a two-way street: The agencies provide not only research participants but invaluable front-line experience on the realities of pain in older adults. Meanwhile, TRIPLL offers resources like expert advice and evidence-based assessments of how well particular programs work. “We know what we do is helpful,” says Schwartz-Leeper, “but in terms of getting funding, we’re always working to have real data for the impact we have on people’s lives.” In the eyes of Dr. Evelyn Laureano, the TRIPLL project had another, less tangible benefit. Dr. Laureano is president and CEO of the Neighborhood Self-Help by Older Persons Project, the agency that runs Casa Boricua, the other Bronx senior center that participated in the Arthritis Foundation program study. To her, having investigators from an Ivy League university eager to understand the needs of her clients — who come from underserved minority communities — was profound. “People who had very low education and literacy levels were being asked by these Cornell researchers what they thought about these programs,” she recalls. “They were involved in town hall meetings in which Dr. Reid and his staff presented their findings and asked for their opinions. This collaboration had an amazing impact on their sense of self-esteem and empowerment. It was a real give and take, and it did a lot to help the seniors understand that their voices are being heard.”

Seed Funding

TRIPLL funds three or four pilot projects annually, providing $5,000 to $25,000 in support with the aim of nurturing findings that will lead to larger grants from the NIH and elsewhere. That’s what happened for Dr. Carol Mancuso, a professor of medicine who won a grant to study how expectations of relief of back pain correlate with patients’ perceived outcomes of spinal surgery. The project garnered additional funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and an internal award from Hospital for Special Surgery; Dr. Mancuso published in the Clinical Journal of Pain and presented at meetings worldwide.

Dr. Carol Mancuso

“At TRIPLL, there’s a wonderful point-counterpoint repartee of ideas,” she says. “That’s valuable compared to the traditional model, where a clinical investigator like myself might partner with only one psychologist or pain management expert.” Dr. Emanuela Offidani, a postdoctoral fellow at Weill Cornell Medicine’s Center for Integrative Medicine, is partnering with the Well Cornell Medicine-affiliated Rogosin Institute to evaluate the efficacy of meditation to relieve pain in older patients undergoing kidney dialysis. Dr. Dimitris Kiosses, associate professor of psychology in clinical psychiatry, is developing a psychosocial intervention for older adults experiencing pain and negative feelings.

Dr. Dimitris Kiosses

“It’s based on the assumption that chronic pain contributes to negative emotions such as anxiety, sadness, discouragement and helplessness,” says Dr. Kiosses, “and vice versa, that negative emotions may modulate or alter pain perception.” Dr. Yuhua Bao, associate professor of healthcare policy and research, used a pilot grant to study pain management and outcomes in older patients receiving hospice care, using a large national data set.

The work, published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, inspired another line of investigation into prescription drug monitoring programs and their impact on physician prescribing. “As I was reviewing the literature, I realized that unsafe and inappropriate prescribing had become a population-level issue that directly contributed to the opioid epidemic,” she says. “So the TRIPLL pilot funding jump-started another area of my research.

Tech Solutions

Thanks to collaboration between Weill Cornell Medicine researchers and counterparts on the Ithaca and Tech campuses, a number of TRIPLL projects are harnessing technology to assess, prevent and ameliorate pain. Ithaca-based information science professor Dr. Geri Gay directs the Interaction Design Lab, which is developing a prototype for a device — worn as a pendant — that users squeeze to report pain, gathering more accurate data than if patients are asked to recall how they felt. “It will be with you all the time,” she says, “and you can assess in the moment how you’re feeling — when you’re walking, going upstairs, trying to sleep.”

Dr. Gay’s lab is working with Ithaca-based associate professor of information science Dr. Tanzeem Choudhury, and mobile health expert Dr. Deborah Estrin, on ways to use cell phones to assess — both actively and passively — how pain is impinging on an older person’s daily life.

Dr. Geri Gay. Photo by Jason Koski/CMG

“One of the big problems is measurement,” says Dr. Estrin, a professor of computer science at Cornell Tech and of public health at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Pain is experienced so individually from one person to another; it’s difficult for people to give accurate quantitative feedback. It’s important to come up with measures that do a good, objective, and sensitive job of helping people report pain, so you can assess if you’re on the right track with a therapy.” Dr. Estrin and colleagues are developing an app that uses a phone’s GPS and accelerometer to see how mobile a person is — say, whether it takes them longer than usual to get out of the house. And with a simple, image-driven interface, users can report whether

“One of the big problems is measurement,” says Dr. Estrin, a professor of computer science at Cornell Tech and of public health at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Pain is experienced so individually from one person to another; it’s difficult for people to give accurate quantitative feedback. It’s important to come up with measures that do a good, objective, and sensitive job of helping people report pain, so you can assess if you’re on the right track with a therapy.” Dr. Estrin and colleagues are developing an app that uses a phone’s GPS and accelerometer to see how mobile a person is — say, whether it takes them longer than usual to get out of the house. And with a simple, image-driven interface, users can report whether pain is interfering with daily activities. “You can’t find out through the phone that they’re having trouble loading the dishwasher because bending over hurts their lower back, so you want people to self-report,” she says. “Instead of asking the same standardized questions, we want to do this in a more personalized way. If somebody doesn’t have steps in their building, you don’t need to ask them about that.” Ithaca-based information science postdoc Dr. Hane Aung, and former graduate student Dr. Mashfiqui Rabbi, PhD ’15, have completed a TRIPLL-supported feasibility study on an app to encourage physical activity in people with chronic back pain. The app creates personalized activity suggestions — such as, “Why don’t you go for a walk around the Central Park Reservoir?” — that are based on a user’s habits, which are automatically tracked by the smartphone’s sensors. Initial data from a small study indicates that targeted suggestions are adopted more often than generic ones, Dr. Aung says, and a larger study is in the works.

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 1.