By Krishna Ramanujan

Postmenopausal women who are obese have a higher risk and a worse prognosis for breast cancer, but the reasons why have remained unclear. A study by researchers from Cornell University and Weill Cornell Medical College, published Aug. 19 in Science Translational Medicine, explains how obesity changes the consistency of breast tissue in ways that are similar to tumors, thereby promoting disease.

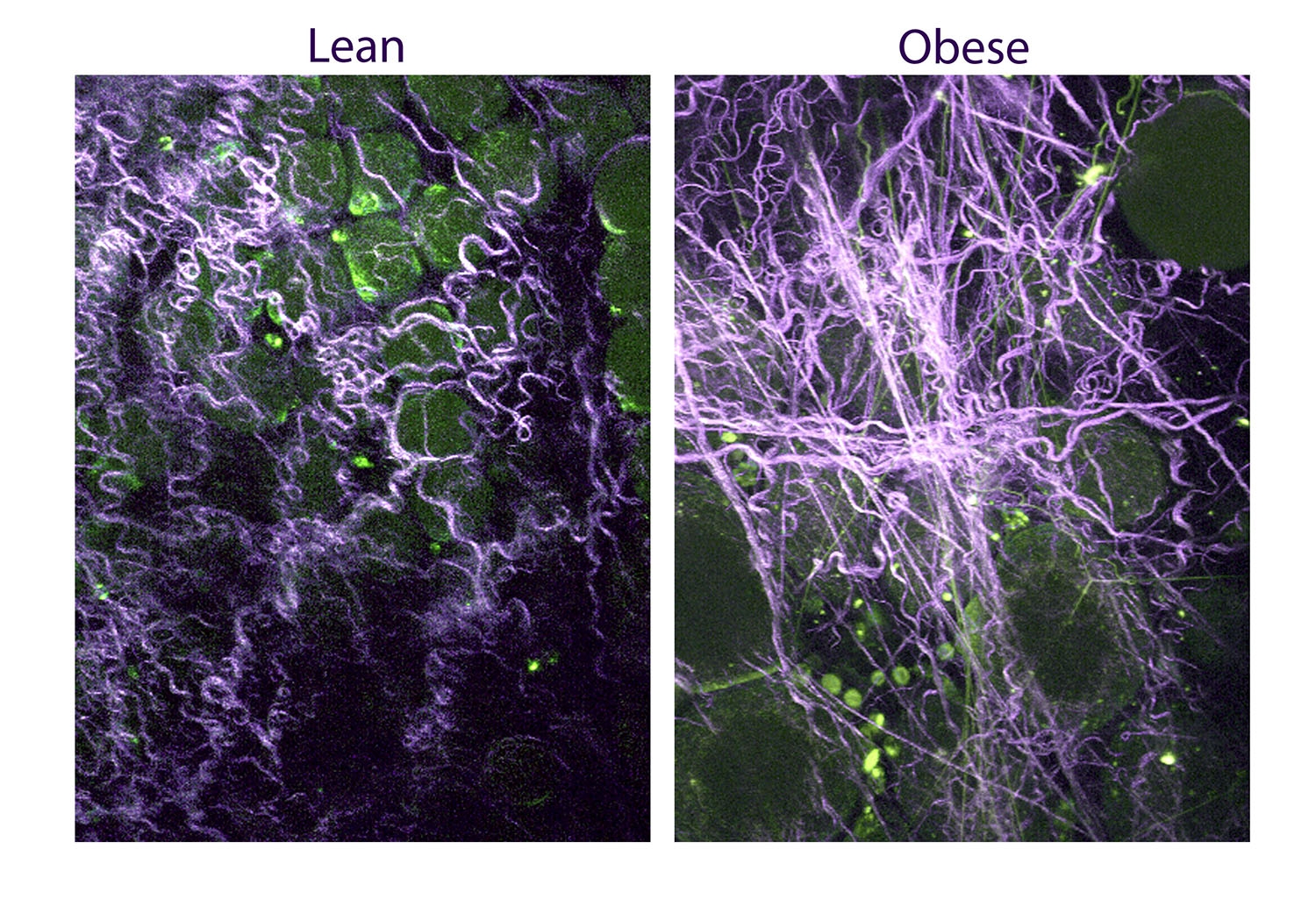

The study of mice and women shows obesity leads to a stiffening of a meshwork of material that surrounds fat cells in the breast, called the extracellular matrix, and these biomechanical changes create the right conditions for tumor growth.

These images reveal curly collagen fibers in normal weight mice (left), but a stiffer meshwork of straight fibers in obese animals. Collagen fibers are labeled magenta, and adipocytes (fat) and inflammatory cells are green. Image credit: Fischbach Lab

The findings suggest clinicians may need to employ finer-scale imaging techniques in mammograms, especially for obese women, to detect a denser extracellular matrix. Also, the results should caution doctors against using certain fat cells from obese women in plastic and reconstructive breast surgeries, as these cells can promote recurring breast cancer.

"We all know that obesity is bad; the metabolism changes and hormones change, so when looking for links to breast cancer, researchers almost exclusively have focused on the biochemical changes happening. But what these findings show is that there are also biophysical changes that are important," said Dr. Claudia Fischbach-Teschl, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and the paper's senior author. Bo Ri Seo, a graduate student in Dr. Fischbach-Teschl's lab, is the paper's first author.

"These findings provide important new mechanistic insights into the connection between obesity and breast cancer," said Dr. Andrew Dannenberg, a professor of medicine and associate director of cancer prevention in the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medical College and a co-author of the study. "Importantly, the current results are also likely to be relevant to other obesity-related cancers. A significant challenge and opportunity will be to develop new noninvasive strategies to identify women with abnormal extracellular matrix."

Fat tissue in obese women has more cells called myofibroblasts, compared with fat tissue in normal- weight women. Myofibroblasts are wound-healing cells that determine whether a scar will form. All cells secrete compounds to create an extracellular matrix, and they remodel and grab onto this meshwork to make tissue. But when myofibroblasts make an extracellular matrix, they pull together — the action needed to close a wound — stiffening the tissue.

But "these are cells in our body regardless of injury," Dr. Fischbach-Teschl said. In obese women, there are more myofibroblasts than in lean women, which leads to scarring and stiffening without an injury in the extracellular matrix. Tumors also recruit more myofibroblasts than are found in healthy tissue, which also leads to stiffer extracellular matrix.

In the study, the researchers studied obese mice and found scarred and stiffer extracellular matrices in the absence of tumors. They also examined tumor-free human breast tissues and found the same pattern of stiffness in the matrices of obese women compared with normal-weight women.

Fat tissue is made up of adipose (fat) cells and adipose stromal cells that also contain myofibroblasts. The researchers isolated adipose stromal cells from the breasts of lean and obese mice and used these cells to make matrices. When tumor cells were added onto the matrix from the obese cells, they grew. Through experiments, the researchers proved the stiffness of this matrix changed a cell's behavior and promoted tumor growth.

They also found that when calories were restricted in obese mice, myofibroblast content in the mammary fat decreased, suggesting a possible therapy for obesity-related cancer.

Many obese women get regular mammograms but signs of disease don't show up because detecting their dense extracellular matrix between the fat cells requires a finer-scale resolution. The findings "may inspire use of higher resolution imaging techniques to detect those changes," Dr. Fischbach-Teschl said. "Right now, people don't look for [stiffer extracellular matrices] as a clinical biomarker."

During plastic or reconstructive surgery following mastectomy in breast cancer patients, doctors may inject adipose stromal cells from obese donors to regenerate tissue. "What our data suggests is that it is really important where these cells are being taken from," Dr. Fischbach-Teschl said. "If you use these cells from an obese patient, they are very different and you may actually be driving malignancies if you implant them."

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Botwinick-Wolfensohn Foundation.

Krishna Ramanujan is the life sciences writer for the Cornell Chronicle.