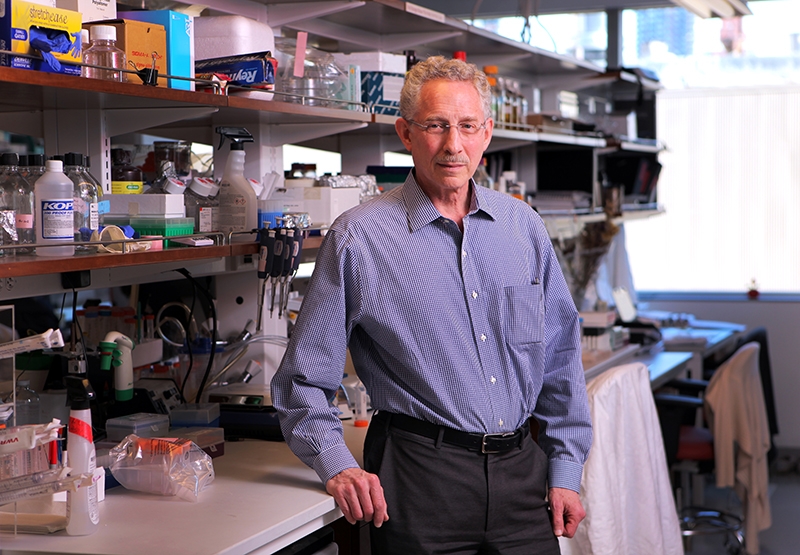

Dr. Carl Nathan

Tuberculosis is an evasive disease. Despite decades of research and increasingly sophisticated and targeted treatment options, it has survived and thrived in humans for tens of thousands of years, killing 1.5 million people and infecting another 9 million in 2013 alone, the World Health Organization estimated.

And the disease's ability to "learn enough about our immune system to survive our efforts to eliminate it" — is exactly what drew Dr. Carl Nathan, chairman of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College, to study it, he said.

Dr. Nathan, who began his career in cancer research, was long interested in how the human immune system sensed and fought tumors. As he worked in this field, he was often visited in his office by Dr. Lee Riley, an infectious disease expert at Weill Cornell who delighted in sharing his discoveries on the basic biology of the bacterium that causes TB.

After continued exposure to Dr. Riley's work, Dr. Nathan decided to shift tracks, and focus on TB, too, he said.

"It just hit me over the head that I could learn about our immune system, which did not evolve to deal with cancer, by asking TB what it learned," Dr. Nathan said.

Today, he heads Weill Cornell Medical's College's accomplished tuberculosis research program, which was recently awarded a seven-year grant worth as much as $45.7 million by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Led by Dr. Nathan, the NIH grant will support the Tuberculosis Research Unit, a research collaboration between six institutions, enhanced by a close alliance with voluntary pharmaceutical partners, that strives to better understanding the biological factors that affect the course of TB infection and treatment. Investigators in the Tuberculosis Research Unit (TBRU) hope to catalyze research findings made in the lab and at Weill Cornell's GHESKIO clinic in Haiti into new, effective agents to replace current TB therapies, which the bacteria has learned to outsmart after more than 50 years of use.

"The TBRU grant is very special, as it allows us to combine basic research with drug development over a period of seven years," said Dr. Dirk Schnappinger, who works with Dr. Nathan in the TBRU, and along with his wife, Dr. Sabine Ehrt, specializes in applying gene silencing and other genetic and genomic approaches to the development of new TB drugs.

"It allows us to work with groups that are experts in all the disciplines that are crucial for the early steps of drug development," he added. "This is a tremendous opportunity."

NIH Grant Reflects Weill Cornell's Distinguished History in TB Research

While the award recognizes the community of researchers studying all aspects of TB today, this type of work has a long and distinguished history at Weill Cornell, Dr. Nathan said.

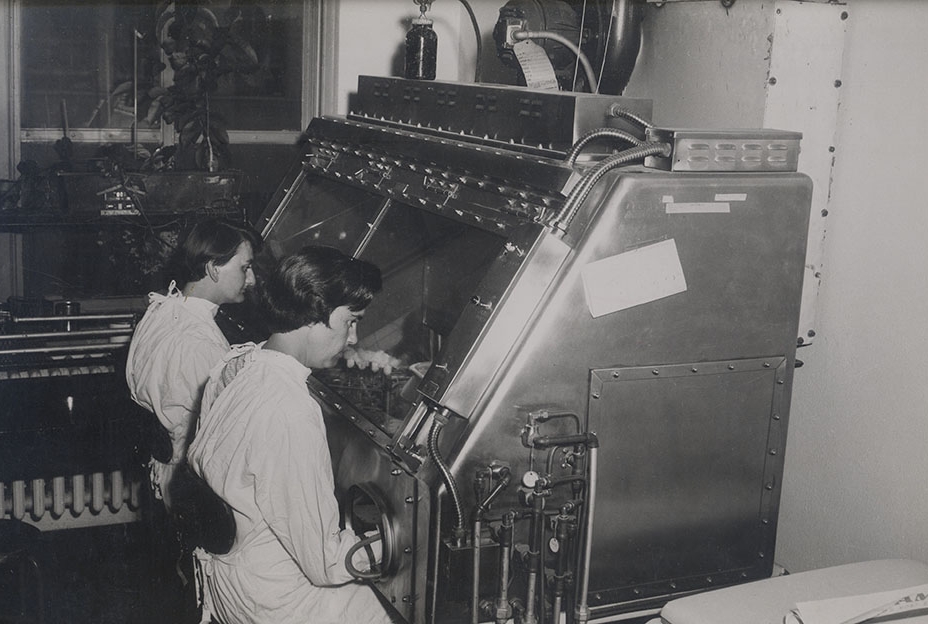

Interest in the disease and tropical medicine began at the medical college in the 1950s, when Dr. Walsh McDermott, a physician who was himself afflicted with tuberculosis, sometimes conducted research on the disease from his hospital bed when the infection flared.

Dr. Walsh McDermott. Photo credit: Peter Erik Winkle

Dr. McDermott was the first to introduce a U.S.-based treatment for TB using isoniazid, a drug that continues to be the first defense against the disease today. He also invented an experimental technique, known far and wide as the "Cornell Model," that tests the limitations of this treatment in mice. Using this model, Dr. McDermott discovered that even the combination of isoniazid and another drug did not treat persistent TB, which is characterized by bacteria that survive despite drug therapy.

"This exposed a shortcoming of combination chemotherapy, an approach that was introduced to medicine in the treatment of TB," said Dr. Nathan, who is also the R.A. Rees Pritchett Professor of Microbiology and the director of the Abby and Howard P. Milstein Program in Translational Medicine at Weill Cornell. "This is where it started, and this is how combination therapy made its way into treatment for cancer, HIV, and many, many disorders."

In 1955, Dr. McDermott was awarded one of medicine's highest prizes, the Albert Lasker Award, for his work on the development of isoniazid.

TB research continued after Dr. McDermott's death in 1981 under Dr. Benjamin Kean, a well-known expert on tropical and rare diseases, and with the subsequent appointment of Dr. Riley, who served as Dr. Nathan's gateway into TB research and is now the chair of the Division of Infectious Disease and Vaccinology at the Berkeley School of Public Health.

In his tenure, Dr. Nathan has maintained and enhanced the medical college's focus on the disease, and has gathered what he calls a "community" of investigators. Together, they're working in the lab to identify potential agents that could solve the issues of persistence and latency. A portion of the TBRU grant will support this bench research.

A "Dream Team" of Scientists in Haiti

TBRU's other focus is on understanding TB biology in infected patients. The center of this work shifts to Haiti, where many strains of TB, including those with drug resistance, exist — representing a microcosm of the world.

At GHESKIO, Dr. Daniel Fitzgerald, co-director of Weill Cornell's Center for Global Health, Dr. Jean William Pape, the Howard and Carol Holtzmann Professor of Clinical Medicine and a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell, Haitian clinical researchers and scientists from the tri-institutional TBRU will engage in clinical investigations on how the bacteria establish and maintain infection in the human body. This part of the grant will be co-directed by Dr. Nathan and Dr. Michael Glickman of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The TBRU grant assembles what Dr. Fitzgerald calls a "dream team" of scientists from New York's three premier research institutions and clinical researchers in Haiti, who will together strive to "address a disease of global importance."

"In most places of the world, we are still using 100-year old diagnostic tests and 50-year-old drugs," Dr. Fitzgerald said, "leading to multidrug resistance that requires two years of treatment with toxic drugs that are not very effective."

TBRU clinical researchers will be empowered to utilize genomic testing and other advanced research methods to discover the molecular underpinnings of TB resistance, as well as to investigate why some but not all patients develop the disease years after being infected. Researchers will accomplish this in a new, 35-room open-air clinic scheduled to open in March.

Each investigator from the numerous participating institutions "brings something special to the table," Dr. Ehrt said. "This is exciting — it's a great opportunity to make a difference."