By Amy Crawford

Last spring, as the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City with full force, Dr. Daniel MacGowan, a neurologist specializing in neuromuscular disease, was asked to consult in a COVID recovery ward. The 40 patients there had all been intubated and sedated, many for weeks—and although they had cleared the infection they were still too weak to leave the hospital. In addition, some were also experiencing unusual neurological symptoms. Some suffered from “foot drop,” a problem with walking that is often a sign of nerve damage, recalls Dr. MacGowan, an assistant professor of clinical neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine and a neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Others reported pain from nerve entrapment in their elbows or knees.

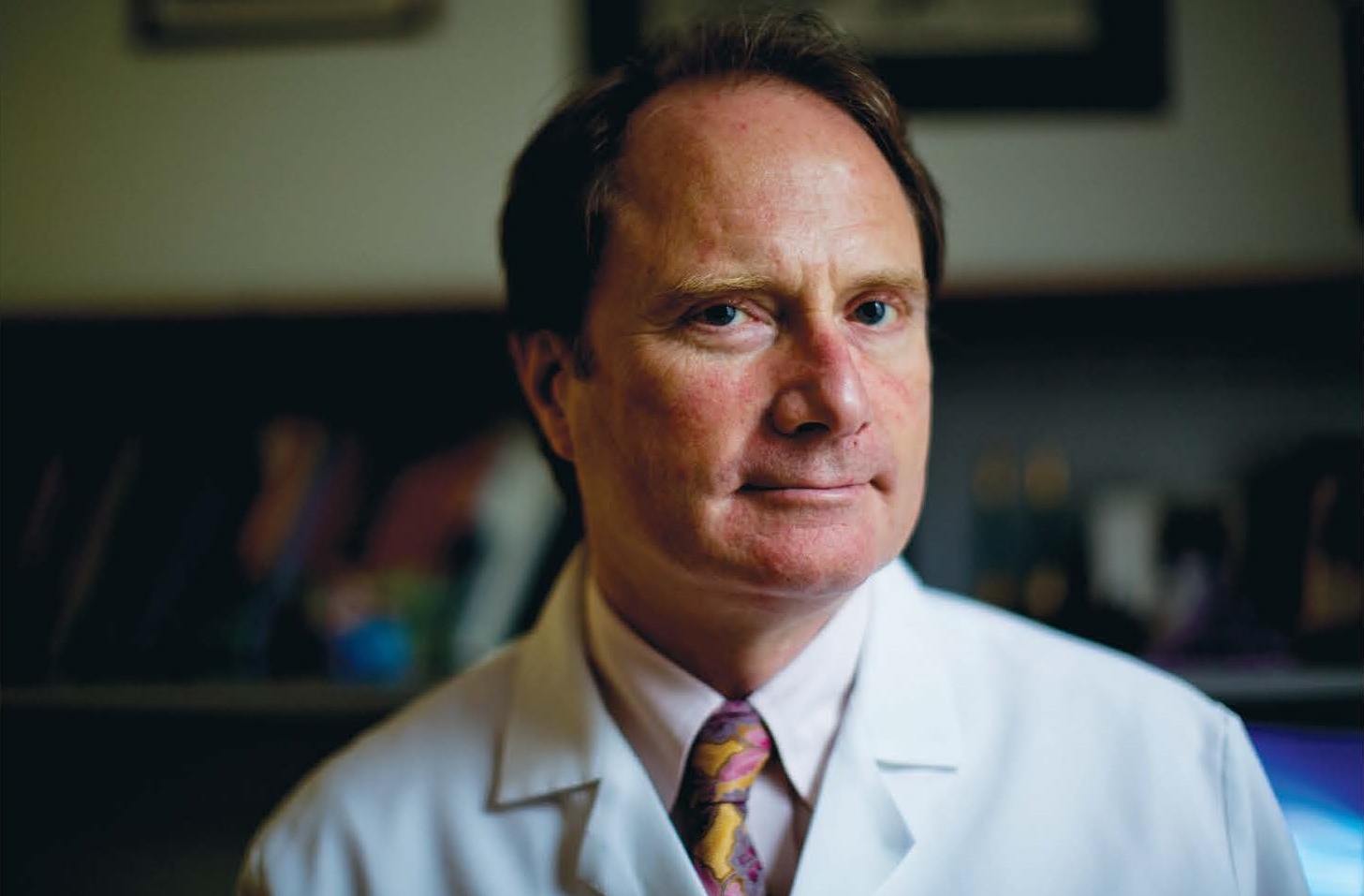

Dr. Daniel MacGowan. Credit: John Abbott

While the convalescent COVID patients’ complaints were different from what would normally be expected in people recovering from a respiratory ailment, some were likely attributable to the time they had spent immobilized in the ICU. But 14 of the patients also presented with something that surprised the veteran neurologist. “They had severe weakness in muscles connected to nerves in the brachial plexus,” Dr. MacGowan says, referring to the cluster of nerves that control the muscles and communicate sensation in the shoulder, arm and hand. “That would not be expected at all, and we assume it was due to the virus.”

Dr. MacGowan and his colleagues could not biopsy the brachial plexus because that would cause further damage, but MRIs and physical examinations revealed that some peripheral nerves were dying or dead. The team came to the conclusion that the coronavirus had damaged the blood vessels that supply the brachial plexus as well as the sciatic nerve, which travels the length of the leg. The resulting clotting disrupted blood flow, causing sections of the nerves—called fascicles—to be starved of oxygen, killing them. “It was surprising,” Dr. MacGowan says. “I’m not aware of other viruses that cause such widespread clotting.”

A year into the pandemic, Weill Cornell Medicine clinicians and researchers are still learning new things about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. But a scientific consensus has emerged that this respiratory virus can, in severe cases, cause damage throughout the body, including to the nervous system and the brain itself. Weill Cornell scientists are now working to investigate these effects—and to find better ways to prevent and treat them.

As Dr. Matthew Fink notes, SARS-CoV-2 is not the only virus that can cause nerve damage—but it does seem to cause more damage than most. “The cognitive symptoms that sometimes result from COVID are also somewhat of a mystery,” says Dr. Fink, the Louis and Gertrude Feil Professor and chairman of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine and neurologist-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell. “And of course we were struck by the prevalence of serious strokes, which is much higher than we’ve seen in other viral diseases.”

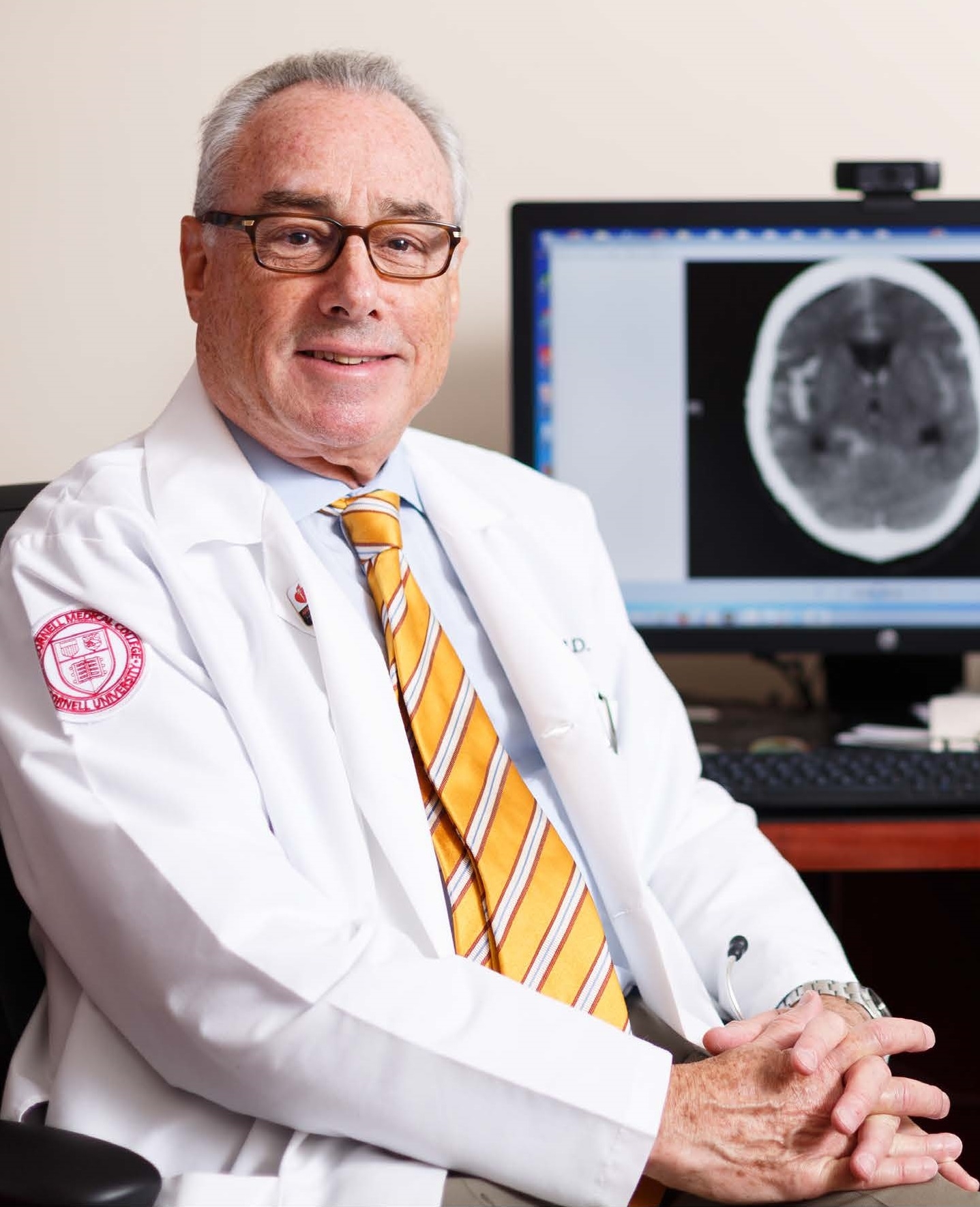

Dr. Matthew Fink . Credit: Tobyn Sharp

Dr. Babak Navi, (MD, MS ’15), chief of the Division of Stroke and Hospital Neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine and medical director of the Weill Cornell Stroke Center, treated a steady stream of COVID patients at the height of New York City’s epidemic last spring. He was familiar with the role that viruses can play in triggering strokes in patients who are already at risk, but SARS-CoV-2 appeared to be doing so at much greater rates. In fact, a study Dr. Navi and colleagues recently published in the journal JAMA Neurology showed that people who were hospitalized or visited the emergency department with COVID had a risk of stroke that was 7 times that of similar patients with influenza. The reasons why remain an open question—one that Weill Cornell clinicians and researchers are continuing to investigate. “It’s not just one thing that leads to stroke in people with COVID,” Dr. Navi observes. “It has to do with increased inflammation as well as with COVID’s effects on blood vessels and the clotting system, on the heart and other organs, and in causing organ failure in very critically ill patients. All these things come together and lead to an increased risk of stroke.”

Anticoagulation medications can help reduce that risk, and as Weill Cornell clinicians gained experience with COVID patients last spring, they developed a protocol to prevent blood clots. But these medications are not appropriate to give every patient as a matter of course, because they also increase the chance of bleeding. For that reason, anti-stroke interventions must be targeted to those who will most benefit—and that requires clinicians to determine stroke risk as precisely as possible.

Preliminary data, Dr. Navi says, suggests that older, male COVID patients who suffer from cardiovascular comorbidities are most vulnerable—not surprising, as these demographic characteristics have long been connected to stroke risk. But to further refine risk calculations, Dr. Navi and his colleagues are using a $96,000 seed grant from Weill Cornell Medicine to develop a predictive scoring system that will identify COVID patients who could most benefit from anti-stroke interventions. The project is a partnership with the American Heart Association, and it will use the organization’s nationwide data set of thousands of people who have been hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Navi hopes the new tool, along with the findings from other research prompted by the association between COVID and stroke, will have benefits long after the pandemic is over. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, stroke affects nearly 800,000 Americans a year. It’s the fifth leading cause of death and a major cause of disability. And stroke also continues to affect people who don’t have COVID—which is why Dr. Navi takes every opportunity to remind people that fear of the novel coronavirus should not prevent anyone who thinks they may be having a stroke from going to the ED or calling 911. Says Dr. Navi: “So many people who would have been eligible for proven acute interventions are now not receiving them because they don’t seek medical attention quickly enough.”

Dr. Babak Navi. Credit: Studio Brooke

Emergency treatments for stroke are well established, Dr. Navi notes, and long-term risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease, are well known. But what’s missing from our understanding is the short-term risk factors—why someone develops a stroke on a particular day, as opposed to sometime the previous month or the following year. It’s there that knowledge gleaned from the current pandemic could help. “Something has to be that trigger, the thing that puts the patient over the edge,” Dr. Navi says. “I think COVID is a trigger in a lot of these patients, and our experience with it is driving home the point that there are things that happen—whether they’re viruses, extremes of stress, pollution in the air, or dehydration—that tip the patient over and lead to the event occurring that day. Perhaps in the future, we can start investigating the utility of preventive strategies in the short-term—for example, starting that patient on aspirin for a week or two—when a short-term risk factor like COVID arises.”

Even patients who don’t experience acute events like stroke sometimes display unusual neurological symptoms. In April, the first wave of patients who had survived serious bouts with COVID began coming off ventilators. Ventilation requires patients to be in a medically induced coma, and in theory they should regain consciousness shortly after anesthesia is stopped—but between a quarter and a third of the COVID patients did not wake up within twenty-four hours. “We were getting three, four, five, sometimes more, consult requests about this every day,” says Dr. Nicholas Schiff, (MD ’92), the Jerold B. Katz Professor of Neurology and Neuroscience in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute (BMRI) at Weill Cornell Medicine, who served as an attending neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell during the height of the pandemic’s first wave. Coincidentally, Dr. Schiff had recently co-authored a paper in Annals of Neurology about a handful of patients who had been sedated and ventilated as they recovered from cardiac arrest—and who, like these COVID patients, had unexpectedly taken weeks to wake up. “They all made good recoveries, and that was a big surprise,” Dr. Schiff says. “One person was still in a coma 6 weeks later, and the chances of them having a reasonably bright outlook were zero in our minds. We just didn’t know it was possible.”

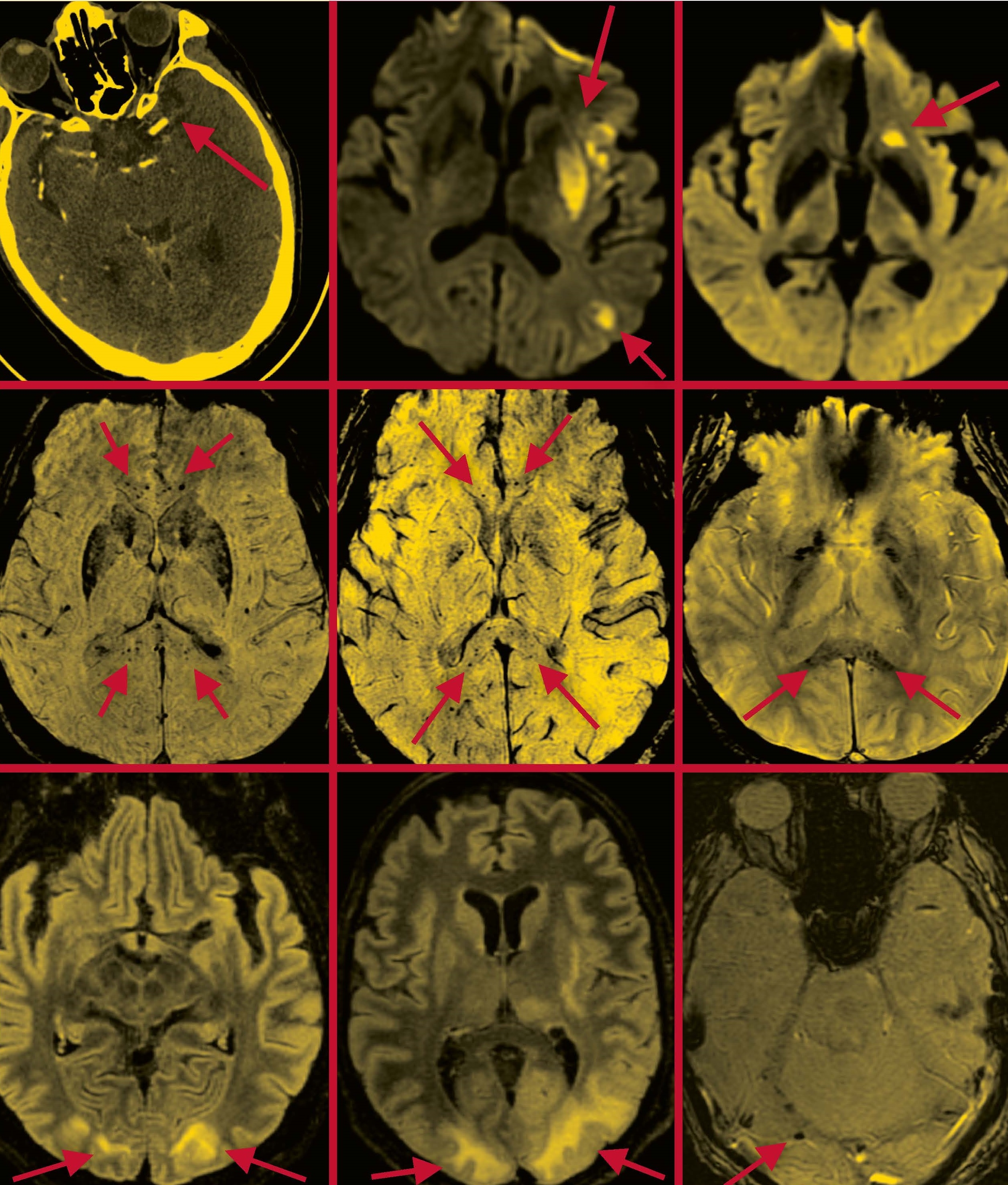

Severe Effects: Scans that appeared in a paper Dr. Navi co-authored in the American Journal of Neuroradiology depict the brains of COVID-19 patients suffering from stroke (top row); microhemorrhages in the corpus callosum region (middle row); and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (bottom row), which is characterized by such symptoms as headaches, seizures, and altered mental status. Arrows in each scan indicate areas of concern. Scans provided

With the cardiac arrest patients’ experience in mind, Dr. Schiff approached the COVID cases with more optimism. MRI scans showed that they did not have brain damage, and over time they started to regain consciousness without any medical interventions—and, despite concerns about long-term effects, they showed slow and continued recovery of consciousness. Dr. Schiff and his colleagues believe it’s important to understand what happened, why some patients might be more at risk, and how waking might be facilitated. “If doctors are not expecting this, it can affect their thinking about whether a patient is going to recover,” he says. “Doctors need to make sure that they don’t decide that the fact that a patient is not regaining consciousness right away means they should be treated with less aggressiveness. If there’s no evidence of an injury to the brain, then we just don’t know yet.”

Dr. Schiff and colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine, in collaboration with Columbia University Irving Medical Center and Massachusetts General Hospital, have received a grant from the James S. McDonnell Foundation to research the phenomenon. They do not attribute the extended waking time to the virus itself, he points out; rather, the many patients ventilated during the COVID pandemic have made common what might once have been rare, offering the team hundreds of patient records to pore over. “We’re doing a deep dive across the three medical centers, looking at all the factors,” Dr. Schiff says, noting that these include patient age, comorbidities, and courses of treatment. “As we build a better understanding of what we think is happening here, it will direct our efforts in finding ways to accelerate the recovery process.”

Of course, recovery from severe COVID does not end once a patient is discharged from the ICU, and it can take a while for patients’ brains and minds to heal. Dr. Abhishek Jaywant, an assistant professor of neuropsychology at Weill Cornell Medicine and a neuropsychologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell, served as the attending psychologist on Weill Cornell Medicine’s COVID recovery units, where his role was to assess patients’ cognition and mood, as well as to help them navigate the complex emotions of recovering from a serious illness. “There was a lot of anxiety and loneliness, from the isolation,” he recalls. “But there was also a lot of resilience, people talking about having a second chance at life and really motivated to work hard at rehab so they could go home.”

In addition to physical rehabilitation, the patients were also working to overcome cognitive deficits including difficulty concentrating and issues with executive function and memory. As with other long-term impacts, it remains unclear to what extent the patients’ cognition was affected by prolonged periods of intubation and sedation, as opposed to the virus itself. Dr. Fink, who has seen an increase in patients complaining of “brain fog,” also believes the stress of isolation is a factor. Dr. Costantino Iadecola, director of the Feil Family BMRI and the Anne Parrish Titzell Professor of Neurology, agrees with the need to carefully monitor COVID patients for cognitive symptoms that persist for weeks or months. Based on his knowledge of the effect of immunity on cognition, he and his coauthors suggested in a paper published in Cell in August that the profound disruption in the immune system associated with COVID may produce lingering, low- grade brain inflammation that could cause anxiety, depression, and cognitive dysfunction.

Dr. Faith Gunning. Credit: Travis Curry

Regardless of the underlying causes, Weill Cornell Medicine psychiatrists and psychologists are committed to helping patients regain as much cognitive function as possible. Dr. Faith Gunning, associate professor of psychology in psychiatry, is conducting ongoing research into the effectiveness of an iPad game developed as an intervention for older adults experiencing cognitive weakness—especially in executive function, a set of processes that include attention, working memory and multi-tasking. Dr. Gunning’s previous research indicated that the technology can help older adults whose cognitive decline is associated with depression. Now, she and her colleagues are hoping to study the technology among patients recovering from COVID. “Given the demographics of our COVID patients, who are often low-income and older, they need to have something they can do at home, so they don’t have the added burden of having to come into the hospital,” she says. “But it’s also not just older patients—many are younger and no doubt would like to be able to return to the workforce.”

As COVID survivors from the first few months of the pandemic returned home and worked to restart their lives, New York, along with the rest of the world, was nervously anticipating further surges of the disease. But in the face of subsequent waves of infections, Weill Cornell Medicine clinicians and researchers will come to the fight knowing much more about the virus, and about how to mitigate and treat its neurological and psychiatric impacts. “Physicians and scientists around the world are working together, collaborating to try to beat this thing,” says Dr. Fink. “Here at Weill Cornell we took care of a huge number of patients—thousands of them. We developed a vast experience, and we’re confident that outcomes and recoveries are going to continue to improve.”

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Winter 2021