Excessive iron buildup in the lungs could be a major cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Weill Cornell Medicine scientists find in a new study. The investigators also believe that they have identified the culprit for the excess: A gene they previously found to increase patients' susceptibility to the progressive lung disease.

For their study, published online on Jan. 11 in Nature Medicine, researchers examined a gene that is tasked with regulating iron uptake in cells, called iron-responsive element-binding protein 2 (IRP2). They discovered that mice that express IRP2 developed the hallmark symptoms of COPD — a condition defined by obstruction to expiratory airflows that makes breathing difficult — when exposed to cigarette smoke, while rodents that lacked the gene remained healthy. A drug given to the symptomatic mice prevented additional lung damage and even reversed COPD's effects.

The investigators say their discovery is significant because they validate the results of a 2009 study that implicated IRP2 in the disease's development and demonstrate how the gene supports COPD. The findings also illustrate that IRP2 may be a powerful therapeutic target.

"At the end of the day, we always like to have an impact on human disease, whether it's improving diagnostics, prevention or therapeutics, and this study actually gets to the therapeutic angle," said senior author Dr. Augustine Choi, the Weill Chairman of the Weill Department of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. "Not only does it validate our previous work, but it also provides us with a really good understanding of how IRP2 functions and facilitates the development of COPD."

COPD, which includes smoking-induced emphysema, chronic bronchitis and non-reversible asthma, is the third-leading cause of death in the United States, affecting more than 20 million people nationwide. It's commonly associated with smoking cigarettes and long-term exposure to air pollution, second-hand smoke, dust fumes and chemicals. But investigators have long wondered if there is a genetic predisposition to the disease.

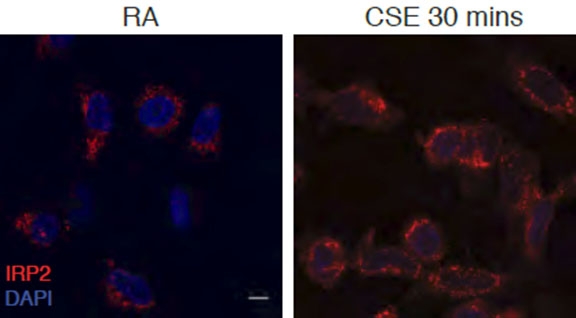

These microscopic images illustrate epithelial cells from a human airway. IRP2 is stained in red in cells exposed to room air (left) and 30 minutes of cigarette smoke (right). Image: Dr. Suzanne Cloonan

In 2009, Dr. Choi and colleagues published a study in the American Journal of Human Genetics that analyzed the genes of patients with COPD and their family members to determine if there was a common genetic link. IRP2 was one of the top hits.

To validate that finding and determine the gene's functional role, the researchers exposed two sets of mice to cigarette smoke for six months. Mice that lacked IRP2 were found to be resistant to the smoke's effects, while the rest developed first inflammation and then emphysema — two very common characteristics of COPD.

The investigators then examined the rodents' lung tissue and found that mice expressing IRP2 had an excessive buildup of iron in their cells, particularly in the cells' powerhouse, called the mitochondria. This indicated that the presence of the IRP2 gene and its corresponding protein caused an increase in iron. While iron is key to the body's metabolism, the balance is delicate – too little or too much can cause disorders such as anemia or hemochromatosis, respectively.

Dr. Suzanne Cloonan

"We think that this excess of mitochondrial iron leads to mitochondrial dysfunction," said first author Dr. Suzanne Cloonan, an assistant professor of biochemistry in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. "The mitochondria cannot behave as normal – they cannot utilize oxygen as well, they cannot make as much energy as they should, and they're stressed out."

Mitochondria are so integral to cell function that the stress caused by excessive iron buildup can lead to inflammation and damage to the lung's air sacs, as well as to cells that line the airways — all of which is common in COPD patients. To offset this imbalance, researchers tested deferiprone (DFP), an orally administered drug that binds to and removes excessive iron from the mitochondria, relocating it to different cell populations in the body for their own metabolic purposes. When given to the sick mice, the drug was able to prevent and even reverse the lung inflammation, Dr. Cloonan said.

DFP is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat the blood iron disorder beta thalassemia. This means that scientists may be able to more quickly apply these findings in COPD to the clinic, Drs. Choi and Cloonan said.

"The drugs we currently use for COPD really just relieve symptoms and don't change the course of the disease," Dr. Choi said. "Our study suggests that we may be able to affect the progression of the disease. A cure would be even better."