As a child, Noelle Desir, 23, suffered from severe eczema. She and her family tried everything to bring the skin condition under control, but without insurance, all they could do was visit the emergency room when she had a flare-up. Finally at age 12, her father, an immigrant from Haiti, secured health insurance for both of his daughters, making it possible for Noelle Desir to see a dermatologist. To Desir’s surprise, the doctor was Black and female, like her.

“It didn’t occur to me that a Black woman could be a doctor. I had never seen a Black physician let alone a Black woman physician, growing up in Long Island,” she said. The doctor explained eczema to Desir and counseled her on managing the condition. Not only did it improve, the experience of having a doctor who looked like her and spent time educating her as a patient also changed the course of her life.

“I made a decision in the car ride home that I was going to be a doctor, and I haven’t changed my mind since,” she said. “Too many times you have a very diverse patient population treated by physicians who all look or speak the same way. The population of physicians should be reflective of the population they’re treating.”

Desir is now working toward that goal as a first-year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College. On Aug. 20, she and 105 of her classmates in the Class of 2025 received their short white coats during Weill Cornell Medicine’s annual White Coat Ceremony. They were joined by 10 faculty members, who helped students don their coats, on The Starr Foundation-Maurice R. Greenberg Conference Center Terrace at the Belfer Research Building for an outdoor in-person ceremony while their family and friends watched the livestreamed event at home, due to ongoing social gathering restrictions.

The ceremony officially marked the beginning of their medical education, which comes at a unique time for healthcare.

“You, the Class of 2025, are beginning your medical studies at a crucial and unprecedented moment in history,” said Dr. Augustine M.K. Choi, the Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Dean of Weill Cornell Medicine. “You have been selected with great care, and we think you have what it takes to tackle the healthcare challenges we face today and make an impact. As you learn about the pathophysiology of disease and the social determinants of health, I urge you to think about ways to make our healthcare system more equitable, so that we can deliver better, more culturally-sensitive care to all.”

“The white coat itself serves as a symbol of our profession but far more importantly, the white coat is a symbol of a commitment to humanism and to the care of the patient,” said Dr. Yoon Kang, senior associate dean for education and the Richard P. Cohen M.D., Associate Professor of Medical Education at Weill Cornell Medicine. “And in the era of COVID, humanism in medicine and truly understanding individual patients’ lives and stories is more important than ever.”

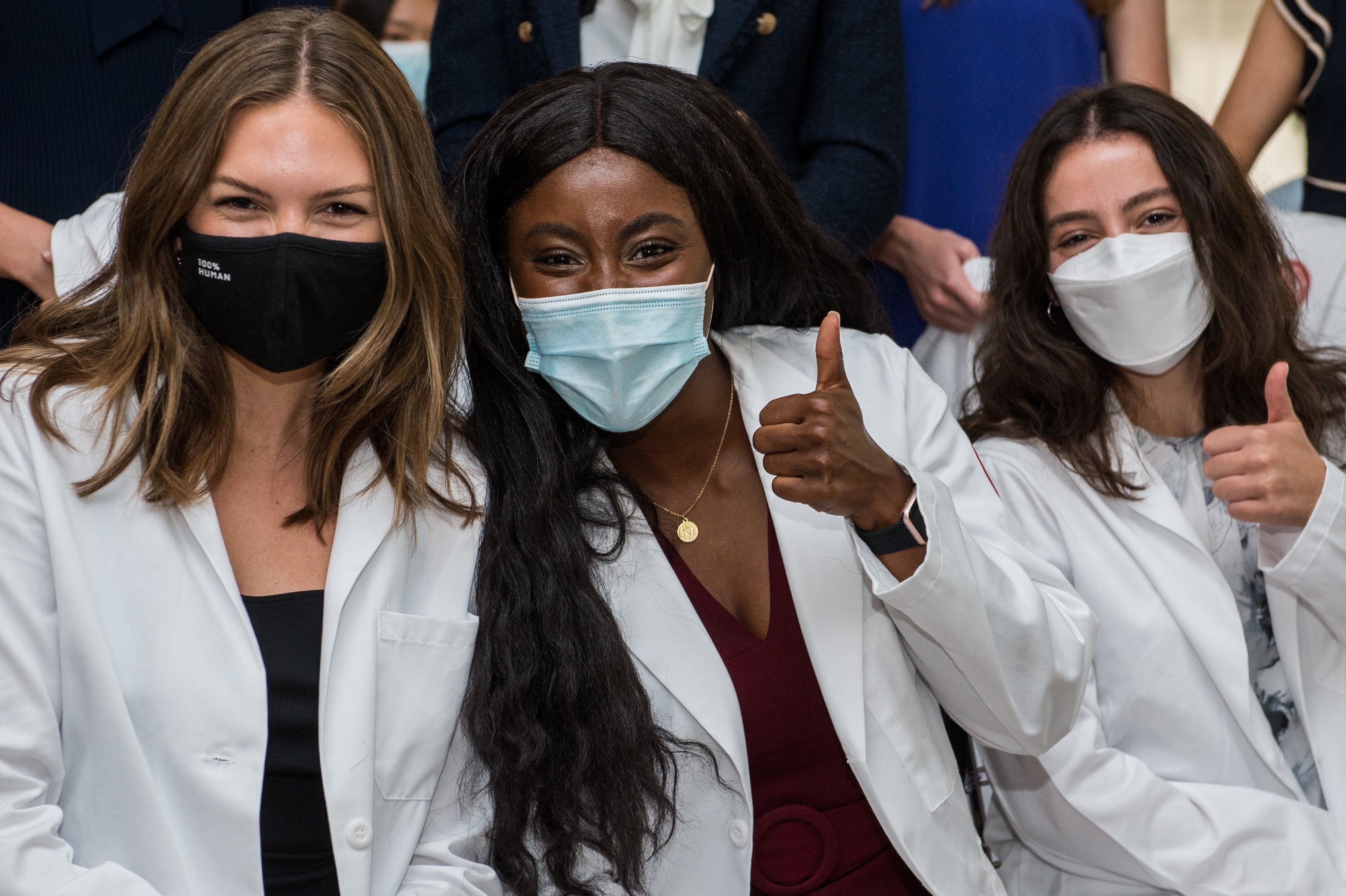

Students in Weill Cornell Medical College's Class of 2025 celebrate during the annual, outdoor and in-person White Coat Ceremony Aug. 20.

When Jalen Matteson, 22, and his brother began acting as interpreters for their two deaf parents at medical appointments, he discovered how much was lost in translation in healthcare settings—where sign language translation often wasn't available. This included that his father had a chronic medical condition—information he hadn’t learned before having Matteson as an interpreter.

“A lot of deaf people learn to just nod their heads and say yes,” said the Rochester, N.Y. native. “I saw from a very young age their struggle to get care from doctors who wouldn’t take the time to help my parents fully understand what they were saying.”

That experience inspired him to become a doctor. Weill Cornell Medicine’s expanded scholarship program, which provides debt-free education to all medical students with demonstrated financial need, will make it possible for Matteson, a first-generation college graduate, to realize that aspiration.

“After I finish my education and begin practicing medicine, I hope to work with the deaf community, and I won’t need to ask for the best insurance or be in a high-paying specialty—which is important because often deaf patients are on Medicaid, Medicare or uninsured,” he said. “I can be a doctor who can help people like my parents understand their health and navigate the healthcare system.”

The Class of 2025 adds to Weill Cornell Medicine’s diverse community. Its students hail from 15 different countries. Women comprise more than half the class, a quarter are from groups underrepresented in medicine and 14 percent are first-generation college graduates. Four students are graduates of the institution’s summer research programs, which provide undergraduate students from underserved racial and ethnic groups or socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds the opportunity to gain deeper insight into science and medicine. Collectively, the incoming class attended 52 different colleges, with six alumni of Cornell University.

First-year medical student Hajirah Gumanneh, center, celebrates during Weill Cornell Medical College's annual White Coat Ceremony, hosted outdoors on Aug. 20, 2021.

While medical school white coat ceremonies only began in 1993, they represent the importance of beginning one’s journey in the field of medicine, said keynote speaker Dr. Anthony Hollenberg, the Weill Chair of the Joan and Sanford I. Weill Department of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

“Donning the coat is a privilege, and with it comes great responsibility,” he said. “Indeed, one cannot overstate the significance of the education you are beginning or the career you will be embarking upon. It is a career and profession steeped in tradition but welcoming change based on new science, understanding past mistakes and inequities, and looking for innovation that will challenge and meet unmet medical need.”

Ana Paola Garcia, 25, knew from an early age that she wanted to work in medicine in her community of Laredo, Texas, a border town of Mexico. Growing up, she helped her parents—who trained as doctors in Mexico and worked in healthcare when they immigrated to the United States—with a makeshift clinic they ran at home. There, they provided care for people who were un- or under-insured. While in college, Garcia participated in Weill Cornell Medicine’s Traveler’s Summer Research Fellowship Program, which exposed her to mentorship from physicians who worked in underserved communities.

“I don’t think I knew what advocating for a community in medicine meant until I did Traveler’s,” she said. “It was nice to see people who looked like me who were physicians.”

Now a first-year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College, she plans to get involved in the Traveler’s program, this time as a mentor. And eventually hopes to return to her hometown to work in her community.

Said Garcia: “I feel like that would make my story come full circle.”