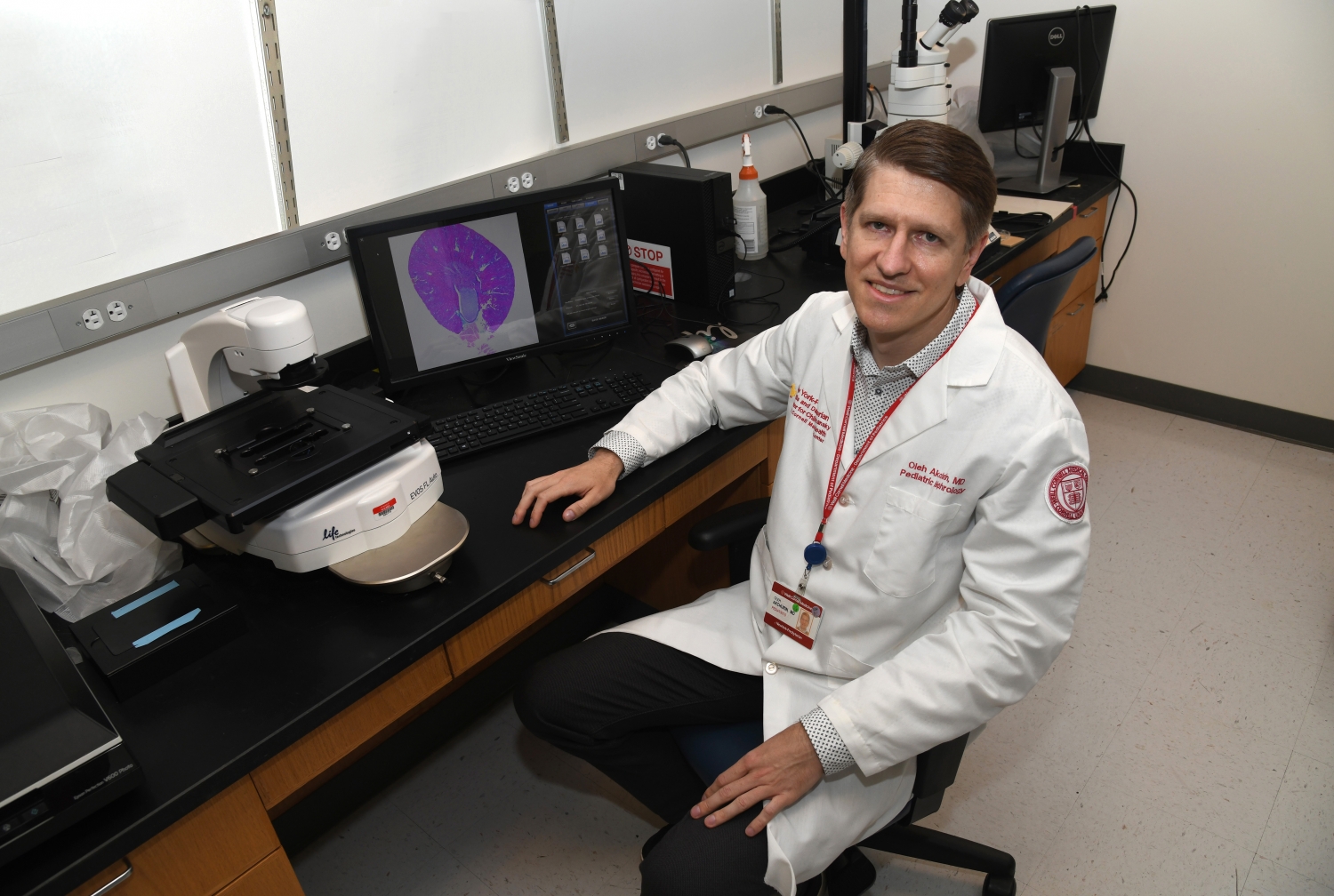

Dr. Oleh M. Akchurin, the Rohr Family Clinical Scholar and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine, has received a 2020 Hartwell Individual Biomedical Research Award from The Hartwell Foundation. The award will provide funding for three years at $100,000 direct cost per year to support Dr. Akchurin’s research project entitled “Immunophenotyping of Peripheral Blood Monocytes to Personalize Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD).”

CKD is a gradual loss of kidney function formerly known as kidney failure. Children with kidney failure grow at a slower rate than their peers, endure poor appetite, anemia, bone fractures and face significant behavioral challenges that may affect learning and social development. The incidence of childhood CKD has been increasing steadily over the last 20 years and while its exact prevalence in the United States is unknown, it is conservatively estimated to exceed 200,000 children. CKD has no cure and inevitably progresses to end-stage kidney disease, which requires dialysis or kidney transplantation. Dr. Akchurin seeks to identify novel cellular and molecular basis of the disease which he believes will inform clinical therapy that can be customized for each patient.

“Currently we don’t have biomarkers that will reliably inform us early on that something is wrong with the kidneys,” Dr. Akchurin said. “Until you lose more than half of your overall kidney function, your tests are still normal. That is the problem.”

Multiple factors contribute to the progression of CKD in children. The disease is frequently complicated by anemia, alterations in iron metabolism, hypertension, and other systemic conditions, each of which requires its separate treatment. Emerging data suggest that some of these treatments may have unanticipated effects on the kidney function and on disease progression in children with CKD. This could be explained by the previously unrecognized action of these therapies on kidney fibrosis, which is the replacement of functioning kidney structures by scar tissue.

For example, oral iron therapy is the most common treatment for anemia in children with pre-dialysis CKD. However, “certain oral iron preparations were unexpectedly found to negatively affect kidney fibrosis in mice in our experiments,” Dr. Akchurin said.

Patients can receive kidney transplants to replace damaged kidneys, but there are currently no therapies to reverse renal fibrosis. “What we can do is try to slow down disease progression,” Dr. Akchurin said, “and one of the ways to do that is to individualize the selection of treatments for children with CKD to minimize adverse and maximize the beneficial effects of these treatments on kidney fibrosis.”

Currently available laboratory tests for kidney function are not sensitive to the timely progression of kidney fibrosis and only signal very advanced kidney damage. Tissue biopsy can provide direct assessment of disease but due to its invasiveness (bleeding and potential loss of the kidney), it is rarely performed in children. To address the unmet need to monitor CKD and guide existing therapies in children, Dr. Akchurin hypothesizes that certain circulating white blood cells, called monocytes, are responsible for the progression of kidney fibrosis. Preliminary data suggests such cells may become protective against renal fibrosis after they take up iron.

Using cutting-edge single-cell transcriptomic approaches, Dr. Akchurin hopes to identify novel monocyte populations that are unique for children with CKD. This may in turn enable development of “liquid biopsies,” which are minimally invasive, as they only require a blood draw to sample the circulating monocytes.

“The process to identify monocytes that will protect against kidney fibrosis can range from either exposing the cells to certain growth factors or medications (including iron) in a cell culture dish to genome editing, which could involve silencing or activating certain genes, and then infusing them back into the body where they will go to the kidney and protect it against fibrosis,” Dr. Akchurin said.

“I was very happy to receive this award,” Dr. Akchurin said. “This will be an exciting project and we are thrilled that The Hartwell Foundation is interested in devoting resources to improve children’s health. I am appreciative of the support from my mentors and peers, who helped make this possible. Dr. Mary Choi, professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, is a great mentor and her contribution to the development of this proposal was instrumental. This really wouldn’t be possible without her.”

Since 2006, The Hartwell Foundation has funded early-stage biomedical research with the potential to benefit children in the United States. The foundation’s goal is to select researchers who have not yet qualified for significant funding from outside sources. In 2020, the foundation selected 12 researchers from 11 institutions. Dr. Akchurin’s Individual Biomedical Research Award also qualifies Weill Cornell Medicine to designate a Hartwell Fellowship to fund one postdoctoral candidate who exemplifies the values of the Foundation, has completed a Ph.D. or equivalent doctorate, and is still in the early stages of career development. The postdoctoral candidate will receive funding for two years, at $50,000 direct cost per year.