An artificial intelligence program developed by Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian researchers can distinguish types of cancer from images of cells with almost 100 percent accuracy, according to a new study. This new technology has the potential to augment cancer diagnosis techniques that currently require the human eye.

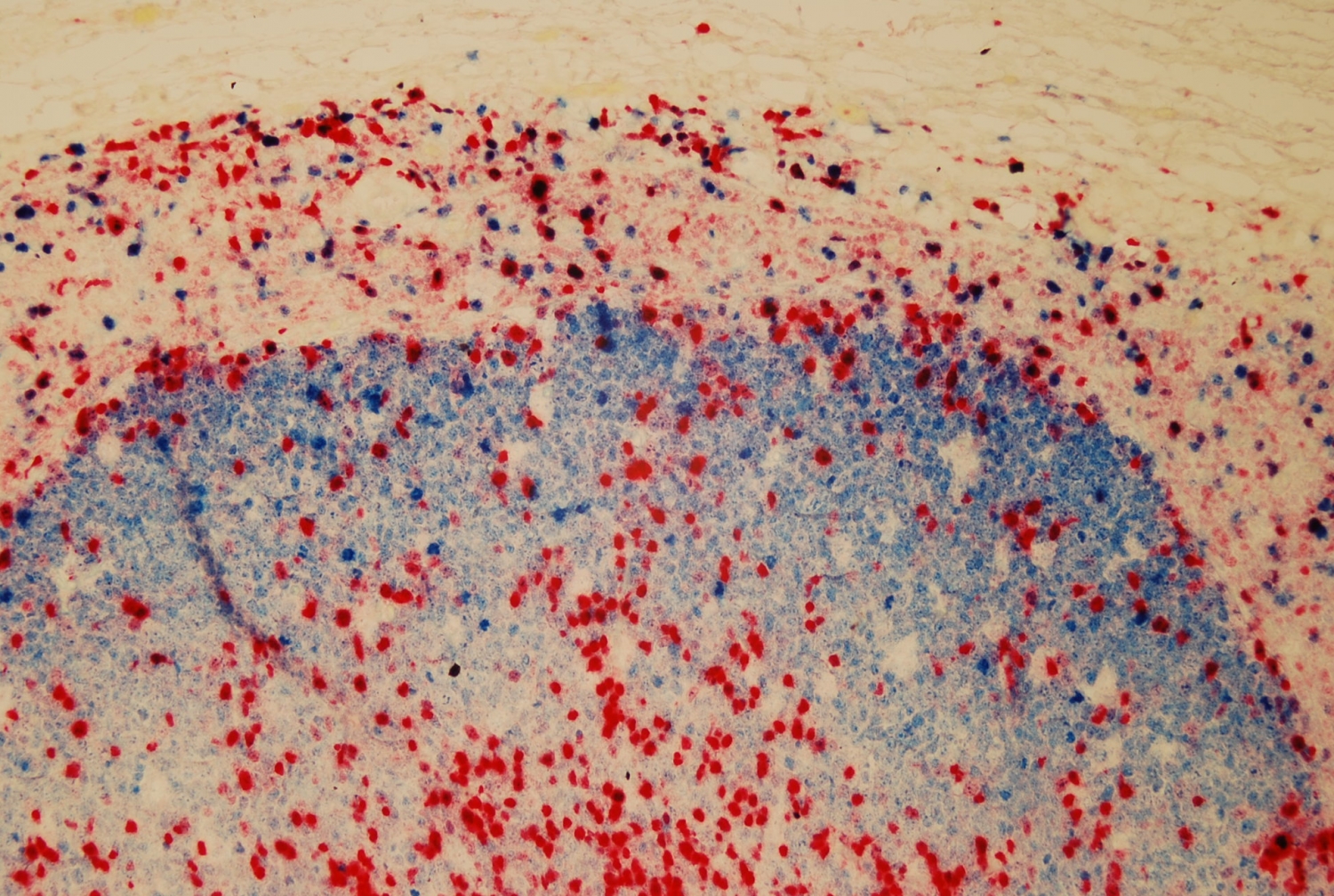

Currently, cancer is diagnosed by visual examination of tissue samples under a microscope. Pathologists consider variables like cell shape, number, mass and appearance when determining whether tissue appears malignant or benign. While accurate analysis is critical to making the right diagnosis, the process can become complicated.

Dr. Olivier Elemento. Photo credit: Travis Curry

“The diversity among cancer cells is very high,” said co-senior author Dr. Olivier Elemento, director of the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, who also leads joint precision medicine efforts at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Things like the morphology of cells, the arrangement of cells within a tumor and the genetic diversity of cancers all make it difficult to see every variation with the naked eye.”

In order to further improve the accuracy of cancer diagnosis, Dr. Elemento and colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian developed an artificial intelligence computer program that analyzes pathology images and determines whether they are malignant and if so, what type of cancer is present. Their results were published Dec. 28 in EBioMedicine.

Dr. Iman Hajirasouliha. Photo credit: Nima Hajirasouliha

The researchers developed what they dubbed a convolutional neural network (CNN), a computer program that is modeled on a human brain. “Just as a human would look at a lot of images and learn to distinguish certain characteristics of a cancer cell, our neural network did the same thing,” said co-senior author Dr. Iman Hajirasouliha, an assistant professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine. In order to “train” the CNN, the team exposed the computer program to thousands of pathology images of known lung, breast and bladder cancers.

In order to test the CNN’s learning, the investigators—including co-first authors Dr. Pegah Khosravi, a postdoctoral associate in computational biomedicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Dr. Ehsan Kazemi, a postdoctoral associate at Yale University—obtained more than 13,000 new pathology images of lung, breast and bladder cancers and ran them through the algorithm. They found that the neural network was able to distinguish the type of cancer in the samples with 100 percent accuracy. In addition, the program was able to discriminate lung cancer subtype with 92 percent accuracy and detected biomarkers for bladder and breast cancer with 99 and 91 percent accuracy, respectively.

“We have demonstrated that an artificial intelligence can have extremely high accuracy and efficiency in distinguishing between cancer types and subtypes,” said Dr. Hajirasouliha, who is also an assistant professor of computational genomics in computational biomedicine in the HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a member of the Englander Institute for Precision Medicine.

The team stresses that artificial intelligence will not replace human pathologists any time soon. Rather, they hope that this technology will help pathologists improve accuracy and speed of cancer diagnosis.

“The neural network can do a lot of work for pathologists,” said Dr. Elemento, who is also associate director of the Institute for Computational Biomedicine, co-leader of the Genetics, Epigenetics and Systems Biology Program in the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center, and an associate professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine. “It can pick up patterns that are very hard for even highly-trained experts to see. But we still need humans to interpret the data and communicate with patients and their treating physicians. Our hope is that this technology makes pathologists more productive and more accurate.”