Dr. Rebecca Baergen has devoted her career to placental pathology

About five years ago, an abnormally small placenta arrived in the surgical pathology laboratory at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. A patient had suffered a miscarriage well into her second trimester, and she craved an explanation for what had gone wrong. Because the placenta controls life inside the womb — providing nutrients to the growing fetus and acting as its lungs, kidneys and immune system — many issues can be traced back to it after birth. Dr. Rebecca Baergen, chief of obstetric and perinatal pathology, was asked to see if it offered any clues.

Because the fetus had short limbs, doctors had earlier suspected skeletal dysplasia, a type of genetic dwarfism, but X-rays and other analyses had disproved this hypothesis. When Dr. Baergen inspected the placenta — which is ideally soft, spongy and beefy red — she noticed a severe loss of blood supply. This had caused some of the placenta's cells and tissue to die and indicated that the fetus hadn't received enough nutrients and oxygen.

While the placenta's appearance suggested preeclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication characterized by high blood pressure, it was ruled out because the mother had no history of the condition. So Dr. Baergen, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, recommended that the woman's doctors check her for autoimmune diseases and blood disorders — and they found that she had Protein S deficiency, a genetic condition that causes over-clotting. In the placenta, this meant that the blood vessels were abnormal, which impeded the transfer of blood and nutrients to the fetus and kept it from growing properly. Doctors treated the mother with a blood thinner, and she went on to have two healthy children. "Most pathologists don't get to talk to patients, but I work with a lot of mothers," says Dr. Baergen, author of the "Pathology of the Human Placenta," the preeminent clinical text on the subject. "It makes a big impression on me when I'm able to help somebody in that way."

Dr. Baergen is one of only a hundred or so pathologists across the country who focus on the placenta, a complex, temporary organ that develops early in pregnancy and is expelled immediately after birth. As recently as five years ago, it was thrown away post-delivery without a second thought. But in her decades-long work, Dr. Baergen has seen the organ gain importance and significance. Today, every placenta that's delivered at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell is stored in a labor and delivery unit refrigerator for one week. This procedure, which Dr. Baergen implemented soon after arriving 18 years ago, ensures that any pregnancy-, birth- or newborn-related issue can be properly investigated. Information uncovered from that research has meant improvements to maternal and neonatal care. And on a larger scale, thanks to the new $41.5 million National Institutes of Health-supported Human Placenta Project, scientists are now studying the organ in a major way. "The placenta is the chronicle of intrauterine life, and it can tell you so much," Dr. Baergen says. "It can be the problem, it can reflect the problem — or even if it's normal, it can help doctors rule things out. It's really important."

About six or seven days after fertilization, the placenta starts forming when the hundred or so cells that form the pre-embryonic mass, called a blastocyst, start differentiating. At that time, the outer layer of cells (called trophoblasts) invades the uterine wall and by day nine develop a primitive support network of vessels, which ultimately becomes the placenta.

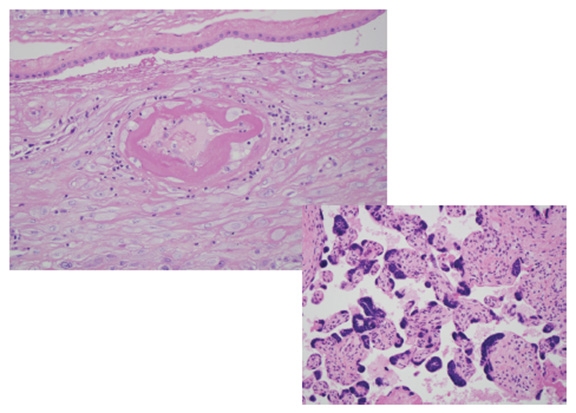

Microscopic analysis: Evidence of maternal vascular disease (above). Right: Overly small chorionic villi, the functional units of the placenta. Photo credit: Dr. Rebecca Baergen

As the blastocyst grows and becomes an embryo, then a fetus, the placenta grows too. By the end of the first trimester, a seamless exchange of nutrients and oxygen takes place between mother and child. Deoxygenated blood is pumped from the fetus through two umbilical arteries to the placenta; there, the arteries subdivide and burrow deep within it, where they continue to spread and multiply — "like branches on an upside-down tree," Dr. Baergen says. Eventually, they become tiny capillaries, which feed into the functional units of the placenta, called chorionic villi. The villi control the nutrient, fluid and oxygen exchange, which takes place between fetal blood from the capillaries and maternal blood being pumped into the placenta from underneath it. This process happens naturally throughout pregnancy; after delivery, contractions force the placenta, which weighs about a pound, to detach from the uterine wall to be delivered as well. "But there are a million things that can go wrong," Dr. Baergen says, and if they do, the health of the fetus and the mother are at stake.

Dr. Baergen came to Weill Cornell Medicine in 1997 from the University of California, San Diego, where she worked with her mentor, Dr. Kurt Benirschke, known as the father of placental pathology. At NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell, she sees the placentas of every patient who has experienced complications during pregnancy or delivery, or whose babies had problems immediately after birth. Through her work, she has uncovered genetic disorders, infections, and a host of other conditions that impede the transfer of nutrients within the organ. She also studies physical problems that can cause fetal death, including cords that are too long, twisted restricted, or inserted into the wrong part of the placenta. Some of these are just random flukes; others, like clotting issues, can be better managed in future pregnancies once discovered; still others are of unknown origin and require further study before they can impact clinical decisions. "Because this discipline is relatively new, there are still so many basic aspects of the placenta to study," Dr. Baergen says. "It's an amazing organ."

—Anne Machalinski

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Vol. 15, No.1.