Diabetes is a disease in which the pancreas either does not produce enough insulin or cells in the body fail to respond to insulin properly. Diabetic patients experience abnormally high blood sugar levels, which can lead to heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, and eye damage. The disease, which affects more than 29 million Americans, is treated with drugs that help to keep blood sugar within a normal range. Steatosis, or fatty liver, occurs in at least half of all diabetics, though the relationship between the two diseases is not clear. Steatosis can also occur in other patients, such as those with hepatitis. It is a condition in which fat accumulates in the liver, causing inflammation and damage to liver cells. Most patients with fatty liver can only be treated with lifestyle and diet changes.

In a study published in the February issue of Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine have identified a new drug that appears to treat both of these diseases at the same time. The drug targets a specific protein, called retinoic acid receptor beta-2 (RARB2), which is critical in the development and functioning of pancreatic cells.

"This is a whole new class of drugs," said senior author Dr. Lorraine Gudas, chair of the Department of Pharmacology and the Revlon Pharmaceutical Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology at Weill Cornell Medicine. "RARB2 is a new target for diabetes treatment. We are also excited because, currently, there is no medicine that effectively treats fatty liver, so this may be a breakthrough therapy."

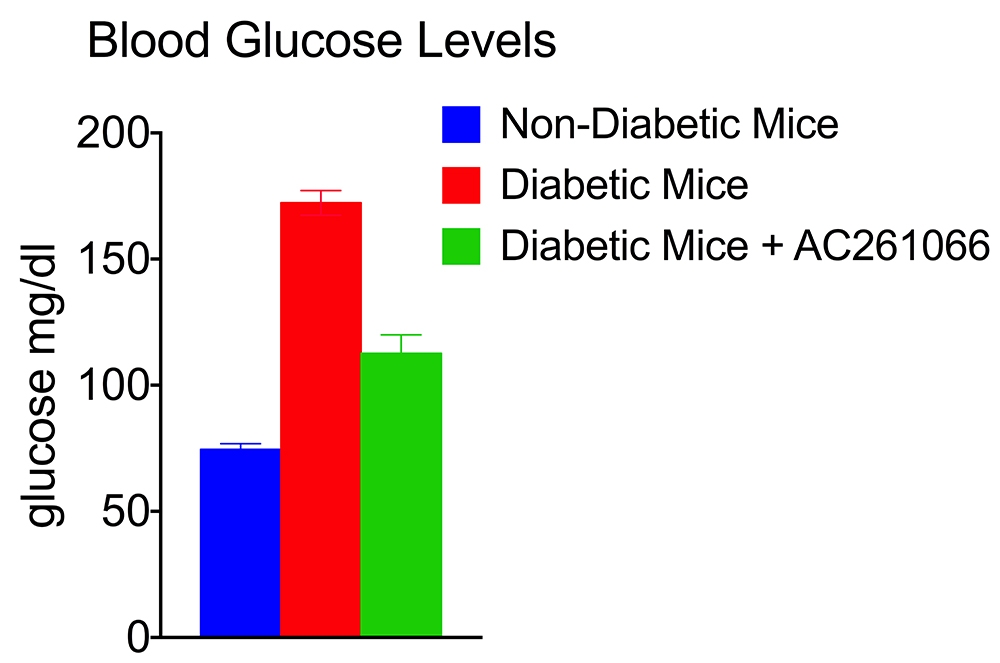

The researchers studied mice with diabetes. The mice were given the new drug in their water. "We found that this drug restored normal blood sugar levels in the mice," said Dr. Xiao-Han Tang, an assistant research professor in pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medicine, who is an author on the paper. "And we also found that it reduced fatty liver symptoms."

The new drug, which has not been tested in humans, might have several advantages over current treatments. First, it is able to be taken orally, which makes it appealing for patients when compared to injectable diabetes medications. Second, it does not cause weight gain in mice. This is critical, said first author Dr. Steven Trasino, a postdoctoral fellow in pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medicine. "Some of the most commonly used anti-diabetes drugs cause weight gain, which can eventually make both diabetes and fatty liver worse. Avoiding that is a great advantage."

The ability to treat both of these diseases at once could result in major benefits to patients. "We think that this drug is a potential, potent anti-diabetic drug for humans," Dr. Tang said. "It's very exciting." Dr. Gudas and her team, which also includes Dr. Jose Jessurun, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and co-author of the paper, are making plans to bring this discovery to the clinic.