With medical Spanish lessons, future clinicians can ask, "¿Cómo está?"

During a hospital preceptorship his first year at Weill Cornell Medical College, Patrick DeGregorio '18 got a glimmer of how a language barrier can impede a doctor's work. After a Spanish speaker, patched in by telephone, helped an attending communicate during an exam, the patient thanked the interpreter -- but not the doctor. For DeGregorio, that small moment underscored the distance that the inability to speak directly can create between patient and physician, and he found the implications worrisome. "It might preclude you from asking the question you need to ask," he says, "and getting a candid answer from your patient about their history."

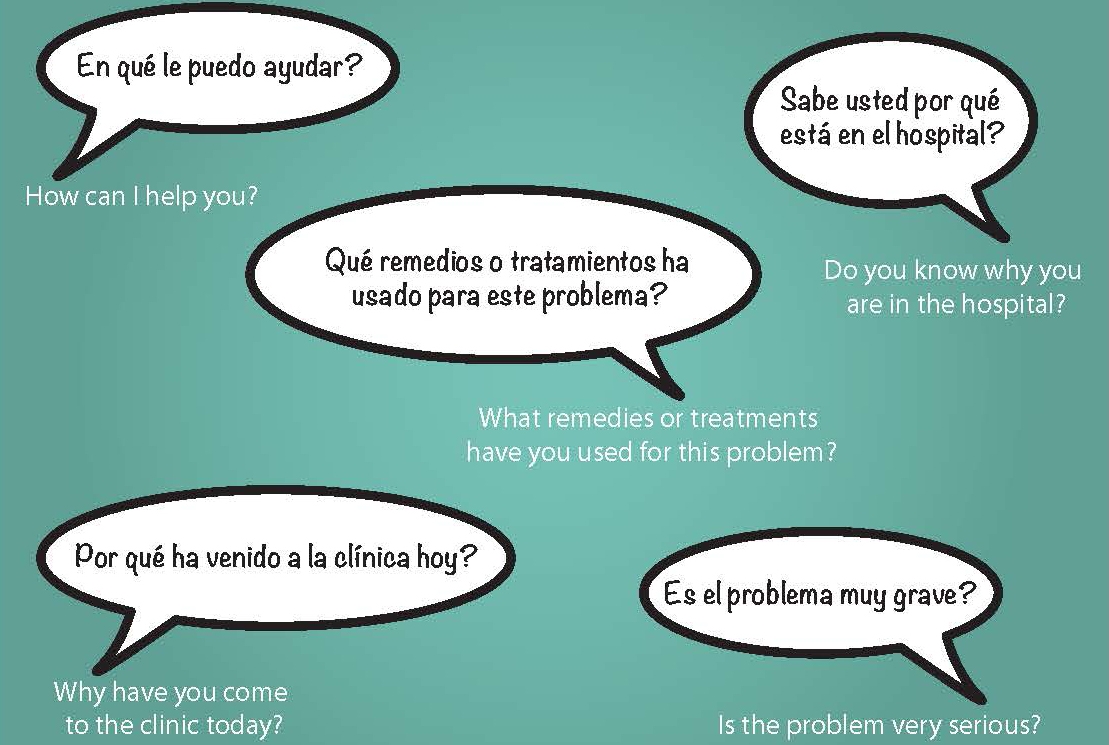

That's why DeGregorio, along with about 50 other students in the M.D. and physician assistant programs, took medical Spanish last semester. The nine-week courses -- divided into beginning, intermediate and advanced sections -- have been offered since 1998. In the introductory group, students learn the terms for many body parts, plus key phrases and common verbs needed for taking histories. In probing cardiovascular issues, for instance, they learn how to ask whether the patient is experiencing shortness of breath ("falta de aire con actividad") or whether they suffer from sleep apnea ("despertarse durante el sueño con falta de aire").

A few weeks into the intro Spanish course, which was held on Wednesday evenings in spring 2015, students sit at desks arranged in a horseshoe shape, trying to reply to Shane's conversational prompts. The atmosphere is designed to be relaxed and non-judgmental, says course organizer Luis Romero '18. "To learn a language you have to stop being so nervous about making yourself look foolish," says Romero, a Cuban native eager to expand his grasp of colloquial variations among Hispanophones. "Here, we all make ourselves look like fools from time to time. If you don't, it means you aren't pushing yourself hard enough."The ability to speak medical Spanish is in high demand in New York City, where Hispanics make up more than a quarter of the population. And as instructor Michael Shane tells his students, a little conversation can go a long way. "I've never heard of anybody saying a patient got angry because their doctor tried to speak Spanish," says Shane, a medical Spanish specialist who also teaches at Columbia and New York Medical College. "They might giggle, but they are more likely to try to teach you."

At the course's intermediate and advanced levels, students not only delve more deeply into the language, but talk about cultural norms. Establishing rapport with patients, they learn, can often be a matter of small courtesies, like asking where someone comes from. ("¿De dónde es usted?") And with more and more students interested in language proficiency, such offerings may someday be expanded to include other tongues such as French and Mandarin, says faculty advisor Dr. Madelon Finkel, a professor of clinical healthcare policy and research. "Anything that will help patients feel comfortable is a good thing, so even with pathetic Spanish you're showing that you're trying to speak," says Paul McClelland '18. "As a medical professional, obviously you're competent at what you do -- but even super-smart doctors can't speak every language."

-- Ken Stier

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine,Vol. 14, No. 2.