High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is often referred to as "good" cholesterol because it transports fat molecules out of blood vessels, protecting against stroke and heart disease. Now, researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College have discovered that HDL in blood also carries a protein that powerfully regulates immune function. Together they play an important role in preventing inflammation in the body.

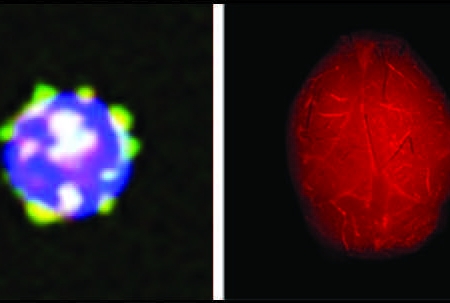

In the study, published June 8 in Nature, the investigators found that a lipid molecule called sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) that is bound to HDL suppresses the formation of T and B immune cells in the bone marrow. In doing so, HDL and S1P block these cells from launching an abnormal immune response that leads to damaging inflammation, a hallmark of many disorders including autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular disease and neuroinflammatory disease, such as multiple sclerosis.

"Our study shows that S1P that is bound to HDL helps prevent inflammation in many tissues," said senior investigator Dr. Timothy Hla, director of the Center for Vascular Biology and a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Weill Cornell. "When there is less S1P that is bound to HDL in blood, there are more B and T cells that can be activated to produce unwanted inflammation."

Dr. Hla has been studying S1P for more than two decades. He discovered that it is a key regulator of vascular function, and that about 65 percent of S1P in blood is bound to apolipoprotein M (ApoM), a member of the lipoprotein family, within the HDL particle. But until this study, the researchers did not know what specific function HDL-bound S1P served.

The team, including first author Dr. Victoria Blaho, an instructor in pathology and laboratory medicine, and researchers from the National Institutes of Health and Stanford University, studied mice that lacked HDL-bound S1P.

Dr. Timothy Hla. Photo credit: Carlos Rene Perez

Mice lacking HDL-bound S1P developed worse inflammation in a model of multiple sclerosis. The reason for this, the investigators found, is that HDL-bound S1P suppresses the formation of T and B immune cells in the bone marrow. While both immune cells help fight infection, an overabundance of these cells can also trigger unwanted inflammation.

The findings help explain why blood HDL levels are such an important measure of cardiovascular health, Dr. Hla said.

"Blood HDL levels are associated with heart and brain health — the higher the HDL in blood, the less risk one has for cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and dementia," Dr. Hla said. "The corollary is that the lower the HDL, the higher the risk of these diseases." Blood levels of ApoM and S1P have not been studied in these diseases.

The findings further suggest that molecules that mimic HDL-bound S1P could be useful in reducing damaging inflammation that has gone awry, Dr. Hla said. Such molecules are not known and will need to be developed in the future.

However, a related S1P1 receptor inhibitor called Gilenya, has already been approved for use in multiple sclerosis, a condition in which the immune system attacks nerve fibers due to unwanted inflammation, Dr. Hla said.

"The unique function of HDL-S1P could be further exploited for innovative therapeutic opportunities," he said.

For this research, Dr. Blaho received funding from the National Institutes of Health (F32 CA14211), the New York Stem Cell Foundation (C026878) and the Leon Levy Foundation (supported through the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute). Dr. Hla received funding from the NIH (HL67330 and HL89934), as well as through Fondation Leducq.