Investigators have long sought the answer to a vexing question: What are the biological mechanisms involved in the development of type 2 diabetes? A recent study from Weill Cornell Medical College researchers suggests that the culprit may be a lack of vitamin A, which helps give rise to the cells, called beta cells, in the pancreas that produce the blood sugar-regulating hormone insulin.

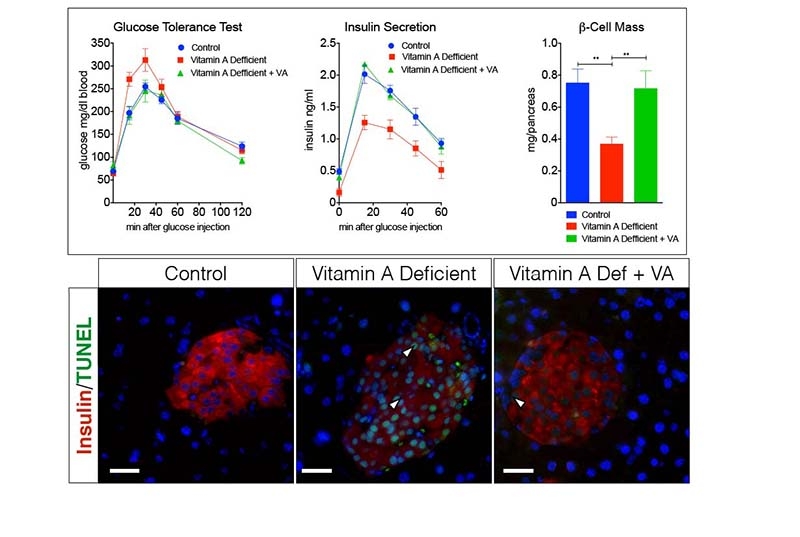

The researchers found in mice models that a lack of vitamin A spurred the death of beta cells, stunting the production of insulin, which is tasked with metabolizing sugars that come from food. These findings, published Dec. 1 in The Journal of Biological Chemistry, may offer new clues into the cause of type 2 diabetes, which is characterized by insulin-resistance, and in advanced cases, inadequate numbers of insulin-producing beta cells.

When the investigators removed vitamin A from the rodents’ diet, they found that the mice began to experience massive losses of beta cells, which resulted in drops in insulin and a big increase in blood glucose. The researchers then reintroduced vitamin A into the animals’ diet and found that the number of beta cells stabilized, insulin production was higher and that blood glucose returned to normal levels.

Because patients with type 1 diabetes and those with advanced type 2 diabetes experience a loss of beta cells, there is a strong interest in developing new treatments that either preserve or replenish them. “From a therapeutic point of view, our research is a very important contribution because there are no drugs available to do this,” said first author Dr. Steven Trasino, a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Pharmacology.

Scientists have understood that vitamin A is essential for the production of insulin-producing cells during fetal development, but whether that role continued into adulthood was not known. The researchers sought to answer that question by using both normal mice and mice that had a genetically impaired ability to store vitamin A.

"While there are thousands of publications on diabetes, there hasn’t been much research on the effects of removing vitamin A from the diets of animals, acting as a model for human disease," said senior author Dr. Lorraine Gudas, chairman of the Department of Pharmacology and the Revlon Pharmaceutical Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology at Weill Cornell. "How the removal of vitamin A causes the death of the beta cells that make insulin in the pancreas is an important question we want to answer. These beta cells in the pancreas are exquisitely sensitive to the dietary removal of vitamin A. No one has found that before."

These early-stage findings raise the question of whether vitamin A deficiency is involved in humans and animals with type 2 diabetes, either through inadequate diet or through a metabolic defect. They also spark questions about whether a synthetic analog of vitamin A could reverse the disease’s effects.

"Our study sets the platform to take these studies further into pre-clinical and clinical settings," Dr. Trasino said.