Genetics, environment, and behavior are all known to contribute to obesity. Now add in a fourth factor: human immunity.

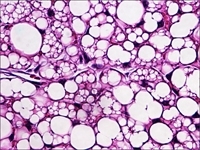

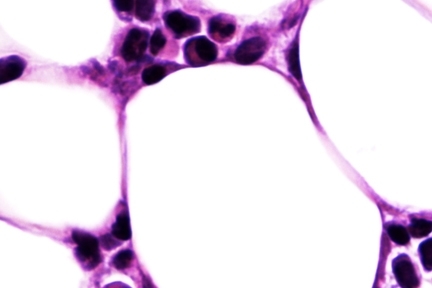

Histologic images above and below showing characteristic murine beige fat cells that are implicated in increasing caloric expenditure and limiting weight gain. Images: Jonathan R. Brestoff and David Artis

In the Dec. 22 issue of Nature, a research team, led by investigators at Weill Cornell Medical College, has found that an immune cell type appears to help burn fat and prevent the development of obesity. The findings suggest new ways of possibly preventing or treating obesity and obesity-related diseases in humans, says the study's senior investigator, Dr. David Artis, an immunologist who leads the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell.

"Understanding how the immune system regulates metabolism and the function of adipose tissue will help guide investigations into immune-based therapies to limit fat accumulation," he says. "Of course, a lot more work is needed before we get there, but this study provides significant insights into this pathway."

The researchers discovered that a subset of immune cells — called group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) — allows fat tissue to take on a metabolically active state that burns calories. This process occurs by inducing the development of a specialized fat-burning cell type called the "beige" fat cell.

Beige fat cells are thought to reduce obesity and other metabolic diseases and are correlated with leanness.

Images: Jonathan R. Brestoff and David Artis

The researchers examined white fat donated by both obese and non-obese study participants, and found decreased levels of ILC2s in obese white adipose tissue. In pre-clinical studies, the investigators found that mice that lacked normal ILC2s became obese and exhibited signs of diabetes.

"Our studies indicate that ILC2s have beneficial effects that decrease obesity and suggest that boosting ILC2s in fat should be explored as a potential therapeutic strategy to treat obesity," says Jonathan Brestoff, a Perelman School of Medicine MD-PhD student in the Artis lab who performed the studies.

While the reasons for immune system involvement in the regulation of fat tissue remain unclear, Dr. Artis says immune control of fat tissue is likely a conserved evolutionary response to body stressors. "For example, imagine that a person infected with the flu is sick, feverish and has no appetite. One can envision the value in reprogramming metabolic processes — such as holding on to stores of body fat — to help the body get through this stressful period associated with infection."

Storing fat is an advantageous response to support survival during times of famine. ILC2 regulation of fat storage may have evolved to help coordinate a switch in metabolic status as food abundance changes. In the context of obesity, however, ILC2s become defective, thereby consequently disconnecting the immune system from metabolic pathways. This might trick the body into a persistent fat storage mode and promote further obesity, Dr. Artis says.

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.