Neurology tends to be a tough specialty. I remember our first day of residency at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, Dr. [Jerome] Posner and Dr. [Fred] Plum [MD ’47] said, ‘For neurological patients, you are their last line of defense. Most people don’t understand neurological disease. They are afraid of it. It’s hard to deal with, and this is your job.’

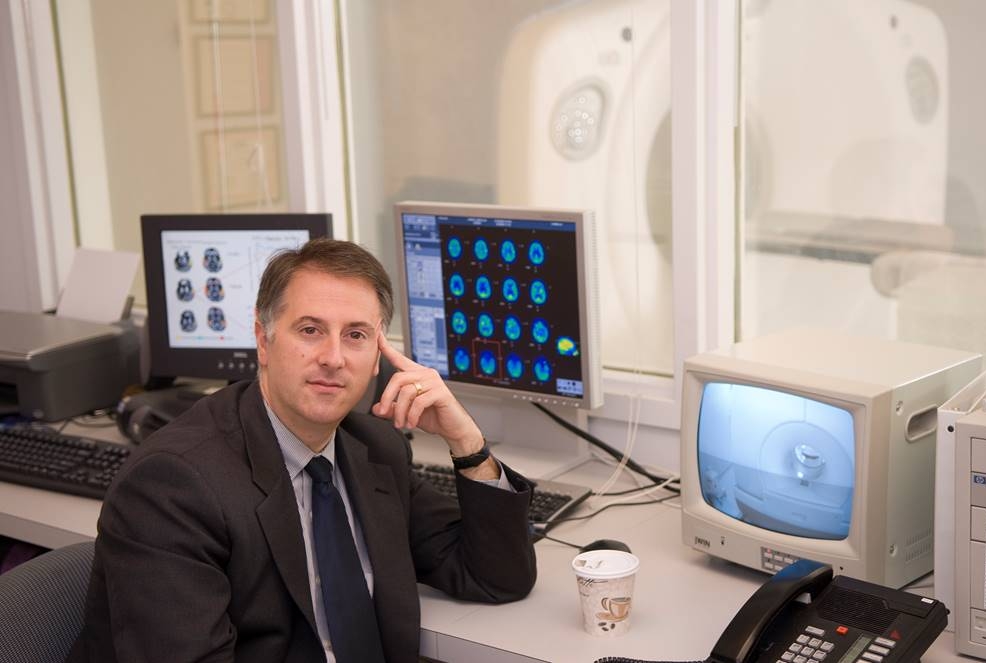

“As an undergraduate at Stanford studying the history and philosophy of science, I got interested in research on modeling areas of the brain that are important to maintaining consciousness. I later became interested in problems of epilepsy that impair consciousness, and I saw it had an intersection to fundamental questions about what we are, how we come to be, and how we’re aware of the world around us. As a medical student I worked on mathematical analysis of electrical activity in the brain, and as a resident, I was putting all those ideas together with observations about brain stimulation in certain patients; for example, you could pour cold water in one ear and restore motor function or speech in some stroke patients. I thought that was fascinating. It suggested that there might be a circuit-level repair mechanism in the injured brain.

“I’ve seen things in my work that most people would never believe. I’ve seen the look of stunned recognition in a family member who has gotten someone partially back—or in some cases nearly fully back—who they were told would never regain any semblance of consciousness. That happens often enough to keep me going. But the frustration is how little this knowledge has been generalized to common, everyday medical practice. Given how fast the science is, it’s going too slowly. There’s still very little infrastructure allocated to helping people with these disorders of consciousness, and things that were considered common knowledge 25 years ago continue to color how this problem is approached.

“When I started clinical practice, there was no ‘minimally conscious state’; it wasn’t a category. Now population studies say that 20 percent of people who remain minimally conscious for months after coma will go back to work within five years. That’s what the science of this is going to do—to allow us to support good outcomes when they’re possible. It could be recovery in someone who isn’t able to live an independent life but can interact with their family— and we’ve seen that. Or it could be a patient who looked like they’d never recover consciousness, getting on an airplane and traveling to a foreign country. And we’ve seen that too.”

This story first appeared in Weill Cornell Medicine, Vol. 17. No. 2