Estrogen-based menopause hormone therapy for women in mid-life should be investigated more thoroughly as a potential strategy for preventing Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, according to a new analysis from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The researchers, whose findings appear Oct. 23 in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, performed a meta-analysis of 6 clinical trials and 45 observational studies, encompassing over 6 million women, in which women were given estrogen-based therapy. The findings suggest that women who took hormones in mid-life to treat their menopause symptoms were less likely to develop dementia than those who hadn’t taken estrogen. On the other hand, women taking estrogen at ages 65 and up did not have a lower chance of an eventual dementia diagnosis compared with peers who did not receive hormone therapy.

“These findings highlight the fact that we need more conclusive research on the possible Alzheimer’s-preventing effect of menopause hormone therapy for women in mid-life,” said study senior author Dr. Lisa Mosconi, director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program and of the Women’s Brain Initiative and an associate professor in the department of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The study’s first author is Dr. Matilde Nerattini, a visiting fellow in neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The estimated lifetime risk for Alzheimer’s disease for a 45-50 year-old woman is approximately 1 in 5 (20 percent) compared with 1 in 10 (10 percent) for a man of the same age. The risks for both sexes are slightly higher at age 65: 21 percent for women and 11 percent for men. Research suggests that estrogen has a protective effect on the brain, and the loss of this protection as estrogen production wanes during menopause may partly explain why females with Alzheimer’s disease outnumber their male counterparts.

But does replacing estrogen reduce women’s Alzheimer’s risk? Studies in animal models suggest that it does, but the question has been difficult to answer conclusively in clinical research, because of the large time gap between menopause, usually in the early 50s, and the onset of Alzheimer’s two to three decades later.

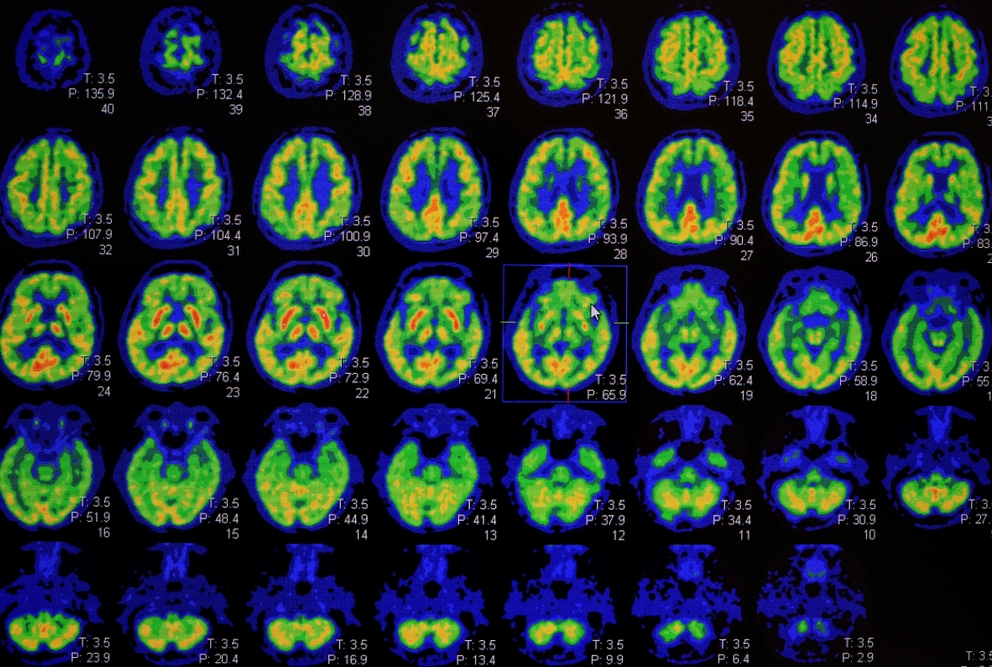

“It isn’t really feasible to run a clinical trial of estrogen therapy for that length of time to look for a dementia-preventing effect,” Dr. Mosconi said. “We need more clinical trials evaluating the effects of midlife hormone therapy on biological indicators of Alzheimer’s disease, which we can now measure using brain imaging and fluids such as blood.”

The clinical trials that have been run to address this question have enrolled older women, and generally have found no protective effect of estrogen against dementia. But Dr. Mosconi notes that estrogen replacement may need to start much earlier, in mid-life at the time of menopause, to be able to prevent or delay the Alzheimer’s process.

In the new study, she and her team pooled the data from the 51 prior studies to compare estrogen therapy in mid-life versus late life. While mid-life estrogen—administered alone—was associated with a 32 percent lower rate of dementia, there was no significant lowering of the dementia rate with late-life estrogen.

Estrogen-only therapy is typically used for women after a hysterectomy. However, in women with an intact uterus, estrogen is often combined with progesterone or progesterone-like hormones, to reduce uterine cancer risk. The analysis suggested that the inclusion of such “progestogens” blunts the preventive effect of mid-life estrogen, lowering the apparent risk reduction from 32 percent to 23 percent, though, again, the data were highly variable and suggest that further research is needed, Dr. Mosconi said.

In the hope of generating more conclusive data, Dr. Mosconi and her team have begun a clinical trial of estrogen therapy in mid-life women, to see if this has an effect on some of the earliest biomarkers of Alzheimer’s.

The work reported in this newsroom story was supported in part by the United States’ National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P01AG026572, R01AG05793, and R01AG0755122. Additional funding was provided by the Women’s Alzheimer’s Movement; and philanthropic support to the Weill Cornell Medicine Alzheimer’s Prevention Program.