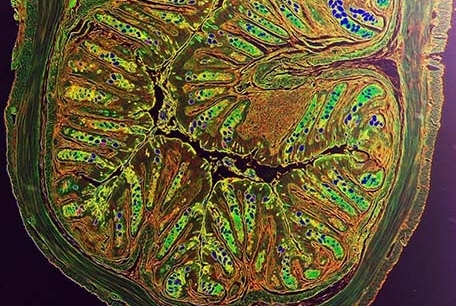

Color-enhanced histologic image showing intestinal tissue damage in a murine model of intestinal inflammation. Image credit: Drs. Laurel Monticelli and David Artis

New insight into how the intestines repair themselves after daily attacks from microbes and other environmental triggers could lead to innovative approaches to treating inflammatory bowel disease, according to new research by Weill Cornell Medical College investigators.

The findings, published Aug. 4 in PNAS, reveal a mechanism that allows the single layer of cells that line the inside of the intestines, called the gut epithelium, to signal the immune system to repair tissue damage caused by the daily onslaught of microbes and other environmental factors that the body encounters. Because a defect in that repair system underlies Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, the two primary forms of IBD, restoring tissue-protective repair mechanisms could reduce the diseases' hallmarks, chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

"We have to maintain gut health by protecting and repairing tissues like the intestine that are constantly exposed to environmental assaults — triggers such as food particles, microbes, pollutants, or things we might swallow — that happen every day," said senior investigator Dr. David Artis, director of the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and the Michael Kors Professor of Immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College. "We found one way these epithelial cells trigger the immune system to promote repair of the barrier that protects intestinal tissue from these constant assaults.

"These are early days in this research," he added, "but these findings provide the foundations for future studies to explore how therapies that promote tissue protection and repair could be developed to combat IBD and other chronic diseases." The research, led by first author Dr. Laurel Monticelli, a postdoctoral associate in Dr. Artis' lab, was designed to understand the biological processes that maintain gut health. The research team found that a component of the body's immune system, called group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2), are key to orchestrating restoration of the intestinal barrier.

"While there have been many advances in understanding how the immune system is causing IBD, less is known about the processes that rebuild the gut barrier and protect against future damage," Dr. Monticelli said.

In the PNAS study, supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, researchers have uncovered a critical feedback loop involved in maintaining intestinal health. When the gut lining is damaged during disease, epithelial cells produce and release a molecule called interleukin 33 (IL-33). The molecule belongs to a family known as the "alarmins" because they act as a chemical alarm system that activates neighboring cells at the site of the injured tissue. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are uniquely suited to act as first responders to this alarm, rapidly producing a growth factor called amphiregulin. High levels of amphiregulin can aid in rebuilding the intestinal barrier by stimulating growth of new epithelial cells and creating a protective layer of mucus that repels future attacks.

"A very sophisticated dialogue is occurring between the gut epithelium and the innate lymphoid cell population," Dr. Artis said, "so tapping into that exchange may be key to maintaining gut health in humans."