It has long been a mystery: Why do breathing difficulties develop in one out of five smokers? What puts these smokers at risk for development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the third-leading killer of Americans, while 80 percent seem to be protected against the damaging effects to airways of trillions of oxidants and chemicals in each cigarette puff?

Genetics plays a role, but one that has remained enigmatic — until now. In a study in the Feb. 3 issue of PLoS ONE, a team of researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College has discovered a biological link between genes known to be associated with COPD and lung function that may explain both the development of the disease and the disparate respiratory effects of cigarettes on their users.

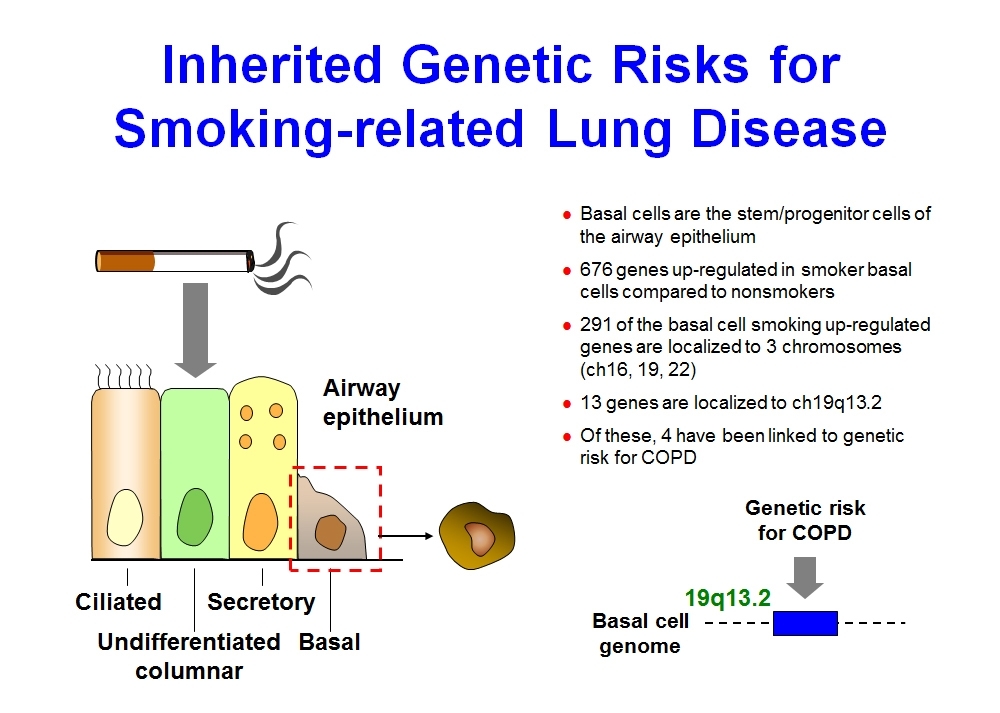

They found, when comparing genetic expression between healthy smokers and non-smokers, that four genes previously associated with COPD are being abnormally expressed in the airway basal cells, the progenitor cells critical to airway function. These genes were among the 676 genes the researchers found were either being over- or under-expressed in the basal cells lining the airways in smokers. These basal cells are crucial to the health of the lung, and the first cells that show damage from smoking.

"This is the first demonstration of COPD risk genes to an actual mechanism within cells that are critical for the maintenance of lung health," says Dr. Ronald G. Crystal, chairman of genetic medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College. "We doubt these four genes are completely responsible for COPD. They are likely part of the story — we believe they play a central role in the very early events that lead to COPD, but they act within a very complex genetic-environment interaction."

A biological link between four genes known to be associated with COPD and lung function may explain the development of the disease. Image courtesy of Dr. Ronald Crystal

The researchers also found that not every smoker had the same level of abnormal expression in the four COPD risk genes (as well as in many of the other genes whose expression differed), which may explain inherited susceptibility to COPD.

"We believe that smoking reprograms basal cells, making some smokers with a certain genetic variant more susceptible to COPD, but we don't know the details yet," Dr. Crystal says. "We are now studying how the basal cells are disordered by smoking."

Basal cells make up 5 to 15 percent of the cells that line the branching airways of the lungs, as well as the windpipe. They contain the critical stem cells that produce the other three kinds of cells that make up, and clean, that protective sheath. "The basal cells replace cells in that lining that are injured or that die, so without them, your lungs will become sick," Dr. Crystal says.

"These abnormal biologic changes are going on in the lungs of smokers who appear to be healthy, but whose lungs show evidence of massive reprogramming," says the study's senior investigator," Dr. Crystal adds.

Dr. Ronald G. Crystal

For this study, the researchers studied 10 non-smokers as well as 10 smokers. Both groups were judged to have healthy lungs, based on chest X-rays, lung function tests and the lack of symptoms of breathing difficulty. Using fiberoptic bronchoscopy — a thin, tube-like instrument threaded through the nose or mouth into the lungs — the scientists sampled the lining of the airway in both groups, retrieving basal cells deep in the lungs.

They then sequenced the genome of these cells, looking at genetic expression of messenger RNA — the molecule each gene makes to produce proteins. The researchers found 676 genes that produced aberrant levels of messenger RNA in smokers. "Smoking essentially reprograms basal cells to have an output of messenger RNA that is different from that of non-smokers," Dr. Crystal says.

To their surprise, they found that 166 genes (25 percent) were found in chromosome 19, known to be home to genes linked to COPD. And in the precise location of these risk genes — an area known as 19q13.2 — 13 aberrantly expressed genes were discovered. Four of these genes were previously linked to development of COPD.

When the science is further defined, the researchers may be able to find targets for potential drug therapy that could protect at-risk smokers against COPD.

"It may be possible to protect basal cells from the toxic effects of cigarette smoke if you shield them in some way, perhaps by shutting off, or modifying the output, of certain genes," Dr. Crystal says.